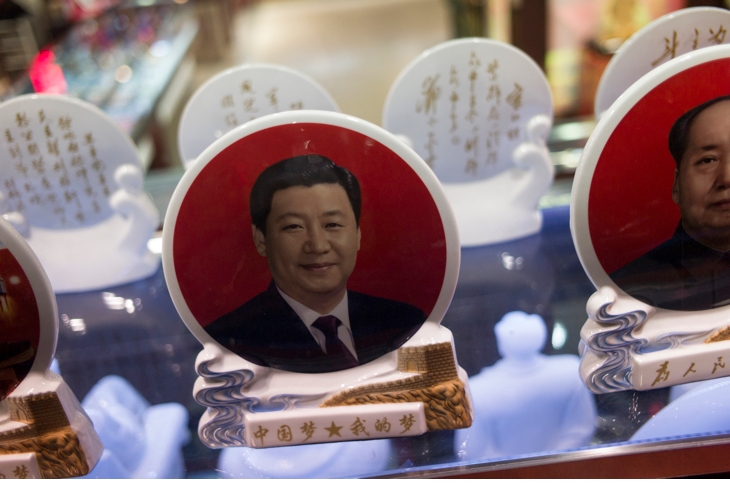

This week, Xi Jinping is close to achieving what Bill Clinton tried and failed to do: to remove the restriction on an individual serving more than two terms as leader of his country. It will mean that Xi is able to remain in charge of China beyond 2023, when his second five-year term will expire, and to become the longest-serving leader since Mao Zedong. Already, the Chinese constitution is being rewritten to incorporate his personal thoughts so a personality cult, too, is being created. For anyone who remembers the hell of the Cultural Revolution, it’s quite a step.

Yet it’s one that’s being greeted with a yawn in the West. Given that the Chinese people did not get to vote for Xi in the first place, it might be argued that it doesn’t matter if he serves a third, unelected term. It might sound undemocratic, but since when can a Communist one-party state be confused with a democracy?

Xi’s rewriting of the constitution does matter because it removes a guard against autocracy that has been in place since soon after Mao’s death in 1976, and was specifically introduced to prevent a personality cult building up around any future leader. It is not necessary to rummage too deeply through recent history – Mugabe, Assad — to understand how leaders with autocratic instincts tend to grow more malignant over time, with a decade often seeming to mark a distinct change in their behaviour. Had any of the above left office after 10 years in power we would not now look upon them as despots.

China was not supposed to head off in this direction. From our Western vantage point we were too quick to assume that rapid economic advance would be followed by democratic reform, as naturally as night follows day. We grew complacent in liberal democracy’s years of triumphalism immediately following the fall of the Soviet Union. It seemed simple: political freedom and economic success went hand in hand. A Chinese middle class would not tolerate autocracy: people wanted the freedom to speak just as much as they wanted consumer goods, and if they were given half a chance to acquire the one they would make sure they obtained the other, too.

China has thrown a proverbial spanner into that theory. The country has become a huge engine of economic growth, embraced capitalism and markets and made stunning progress on poverty reduction. Its people have become richer faster than anyone could have imagined a generation ago, and now it’s the turn of British political leaders to turn up cap-in-hand, asking for business investment. Once, we imagined that we’d offer them greater access to world markets in return for greater reform. But as Hinkley Point shows, we have become pathetically dependent on Chinese investment for our public utilities – with democracy nowhere to be seen in China.

There is also little sign of mass anger among the Chinese public at Xi’s grab for long-term power. On the contrary he seems popular. If he were to submit himself to the people for a popular mandate he might well win one. After Tiananmen Square it was easy to imagine that China was about to erupt into popular revolution, just as Eastern Europe did a few months later. Yet nearly three decades on, that suppressed protest seems an odd, one-off affair.

So Western leaders have given up preaching democracy – and pursue trade missions instead. Rather than shape China’s foreign policy and priorities, the UK is letting China shape ours: British Prime Ministers have now learnt not to raise human rights when they visit – Theresa May was praised for not doing so by Chinese state media, which noted with approval that Emmanuel Macron also kept quiet.

This has left the West in a quandary. The economic success of the Chinese model – a market system without political freedom – makes it much harder to present our own liberal democracy as something to emulate. And when it comes to tackling poverty, China has made more progress inside its own borders than has been made by any amount of Western aid. If you are an African nation being offered Chinese investment, or a Central Asian republic which stands to benefit from China’s One Belt, One Road initiative to open up the economies of the region through infrastructure investment, why look to the West for inspiration?

You might well be tempted instead to agree with the words of China’s English Language propaganda paper which has written: ‘key parts of the Western value system are collapsing. Democracy, which has been explored and practiced by Western societies for hundreds of years, is ulcerating.’

A generation ago, the argument for liberty and limited government was made regularly and vigorously. Now, such arguments are hardly heard at all – indeed, the basic principle of free speech is under regular assault in many of the campuses where the Western leaders of tomorrow are being trained. If there has been a notion that the argument for democracy has been won, then it can be dispelled by a look at what’s happening around the world. Yes, Western governments ought to pursue wealth and trade – but also promote their values. We can be sure that President Xi will be doing the same.

Comments