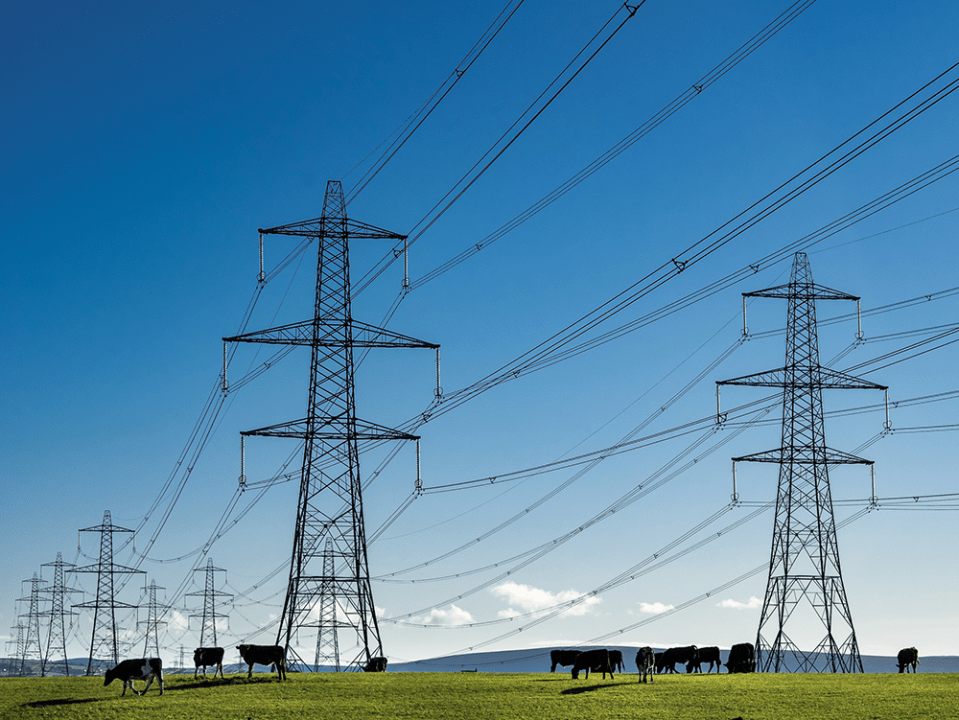

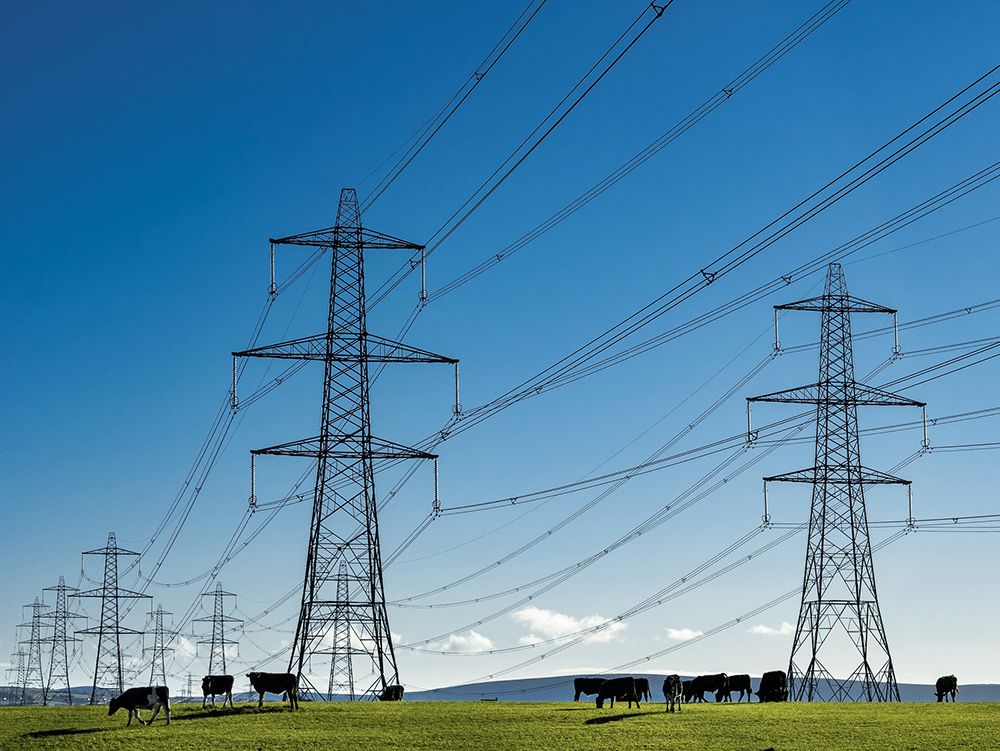

At the end of last month, a fire at an electrical substation in Maida Vale caused chaos in west London. Homes lost power. Transport services ground to a halt. It came in the same week as outages across Spain and Portugal and just a few weeks after a fire at another substation caused Heathrow airport to shut down. We also know that the British government is drawing up contingency plans for Russian attacks on energy infrastructure. All of this raises an important question: how resilient would the British state be in the face of a determined effort to cripple its power grid?

The blunt answer is: not very. David Betz, at King’s College London, has long warned that Britain’s national infrastructure is dangerously vulnerable to simple tools such as hammers and hacksaws. Politicians often preoccupy themselves with the abstract threats of the digital age while ignoring the reality that substations, transformers and transmission towers remain exposed to the age-old dangers of vandalism, arson and explosives.

Academics such as Betz believe financial crises and ethnic tensions under the surface of British society are creating the conditions for not just dangerous unrest but outright civil war. Betz thinks this conflict will take place between diverse groups in the cities and ‘nativists’ in the countryside, the latter of whom will have easy access to critical infrastructure outside of cities.

Our security services would be stretched far beyond their capacity to foil plots by individuals and groups. During the Troubles, the IRA plotted to knock out power stations in south-east England using bombs. As recently as 2022, an extremist group in Germany planned to destabilise the government in part by disabling access to the energy grid, with conspirators including former members of the German army. In that case, security services were able to thwart the plot. Britain might not be so lucky.

We have a number of substations which serve the National Grid and make for particularly ripe targets. Britain relies on more than 300 of these facilities, many containing oil-filled transformers that are indispensable to the flow of electricity. The destruction of one transformer could cause extended blackouts in large areas. If several were attacked simultaneously it could lead to national paralysis. Much of the information that an individual would need to carry out attacks on the grid is already available on the internet through open-source research conducted mostly by hobbyists.

Britain has spent

decades designing systems

for efficiency, not resilience

Other critical infrastructure such as hospitals and airports could also be targeted. The recent incident at Heathrow demonstrated how little redundancy – a technical term for back-up capacity – some key sites possess. A single fire disabled the main feed to the airport and, it appears, a back-up system as well. Power was lost. Flights were grounded. That turned out not to have been the work of a hostile actor. But it could have been.

The Royal United Services Institute, Britain’s oldest defence thinktank, has also pointed out the relative ease with which physical infrastructure can be sabotaged. High-voltage transformers cannot be quickly replaced. Many are custom-built. A co-ordinated attack on a few carefully chosen substations could, in theory, lead to cascading blackouts and significant economic disruption. The fact that these facilities are often protected by little more than a chain-link fence and a CCTV camera ought to concern us more than it does.

The government is not entirely asleep at the wheel. The National Protective Security Authority has for years advised utilities to fortify key sites. Select substations have received upgrades, including reinforced fencing and improved surveillance. The National Grid itself works closely with law enforcement, and all incidents, even accidental ones, are treated as potential attacks until proven otherwise. When the Heathrow substation caught fire, counter-terrorism officers were dispatched immediately.

Too much of the system still runs on trust, however. Trust that vandals won’t climb fences. Trust that insiders won’t turn rogue. Trust that a would-be saboteur will be deterred by a warning sign. As Betz has argued, the liberal state is constitutionally uncomfortable with defending infrastructure. Liberals prize openness. But openness has its price.

The outages on the Iberian Peninsula last month further underline the fragility of our interconnected systems. Most of Spain and Portugal lost power, apparently due to a technical fault. No evidence of sabotage has emerged, but the timing was suspicious, coming just weeks after unexplained incidents involving undersea cables and pipelines. Spain’s Prime Minister even called Nato to discuss the blackout, underscoring the international anxiety it triggered. Britain, for its part, depends heavily on undersea interconnectors and gas pipelines – particularly the Langeled pipeline from Norway. Their destruction would not merely dim our lights but potentially freeze our homes.

The Royal Navy has stepped up patrols. In January, the government publicly named a Russian spy ship observed loitering over North Sea cables. Such steps are welcome, but they also signal how perilous the situation is. Experts have called for more diversified routing and back-up power arrangements for critical hubs such as hospitals and airports. The National Grid has invested in mobile substations and spare equipment, but these only go so far. Should multiple sites be attacked simultaneously, the current stock would almost certainly fall short.

Britain’s ‘black start’ protocols, designed to restart the grid from zero, are rehearsed on paper and in simulation. But whether they would work under pressure – or in the face of repeat attacks – remains an open question. The state is also encouraging utility companies to conduct more thorough background checks on staff, recognising that insider threats are often the most dangerous. But even the best background checks can’t account for radicalisation after employment.

Whatever your view on Betz’s belief in the possibility of civil unrest, it is a measurable fact that social trust is plummeting while radicalisation of different stripes intensifies, making the case for the precautionary principle with infrastructure unanswerable.

Britain has spent decades designing systems for efficiency, not resilience. We have streamlined, optimised and outsourced. But we have not thought hard enough about what happens when a transformer blows up – or is blown up. The recent incidents in London and southern Europe ought to jolt us from complacency. Not every power cut is an attack. But every power cut should remind us what an attack could achieve.

Comments