Teenagers, in my experience, divide into the unmotivated and the motivated sort. You can spot the symptoms: given a free day, the unmotivated one will go out to buy a new phone charger, while the motivated one will go on an advanced sailing course. If you’re the unmotivated sort, read no further. This piece is not for you. You have as little chance of getting a place at an American university as my lazy dog does of winning Crufts.

And when I say motivated, forget the Oxbridge level of motivation. Doing well in A-levels, filling in a Ucas form, managing to cook up a personal statement claiming to be passionate about your subject, going for a couple of tricky interviews; that’s an absolute doddle, an M&S picnic, compared with the kind of motivation you need to have to get into a US university.

For that, you need the dazzling all-round brain power of Leonardo da Vinci combined with the passion of Emmeline Pankhurst and the single-minded organisational skills of Judy Murray. Oh, and it helps to have the spending power of Elton John, because going to an America college for four years will set your parents back at least $300,000, unless you’re lucky enough to get a scholarship — and those are hard to come by if you’re not a rowing prodigy.

You’ll need to start young: Lisa Montgomery, chairman of Edvice, which provides guidance to those applying to US universities, tells me that she recommends starting to work with students at 14 or 15 in their pre-GCSE year. ‘I like them to think about how they’re going to be spending their summers,’ she says.

‘They should be doing something to enhance their extra-curricular or academic profile. My guideline is that you should spend approximately 50 per cent of your summer in support of something you care about. It could be riding a bike across France — but you’ll need to be able to defend why you do it.’

She warns her new clients that the basic form-filling to apply to the recommended number of ‘schools’ (eight to 12) will take a minimum of 80 hours. But in order to have a hope, you’ll need also to live the kind of life that makes you a worthy candidate.

So, if you’re a ‘can’t be bothered’ kind of teenager, forget it. Go for Bristol, Nottingham, London, Newcastle, Edinburgh, St Andrews… places that you can basically get into from your bed with the right academic results.

The astonishing thing is that there’s a huge and growing trend for applying to US universities from British independent schools. (Lisa Montgomery, who charges around £20,000 to guide pupils and parents through the process, currently has students on her books from Charterhouse, King’s Wimbledon, St Paul’s, St Paul’s Girls, Westminster, Wycombe Abbey, Winchester, Eton, Harrow, Godolphin and Latymer and Latymer Upper, among many others.)

In fact, there is such a huge demand for US universities that many schools — including St Paul’s and Wellington — now have whole departments to handle applications, offering half-term trips to visit campuses and intensive tutorials to prepare pupils for the three-hour SAT and ACT tests you have to sit, which require high standards in maths, the sciences and English.

You must do well in these (thankfully centralised) three-hour tests, but that’s by no means enough. American universities are looking at the ‘whole person’, so you need to list up to ten extra-curricular activities on your form and you are also expected to write impressive supplementary essays that demonstrate what a socially aware, actively useful, thoughtful person you are.

Tufts University in Massachusetts calls this ‘Let Your Life Speak’. Typical recent essay questions: ‘In a time when we’re always plugged in (and sometimes tuned out), tell us about a time when you listened, truly listened, to a person or a cause. How did that moment change you?’ And ‘Whether you’ve built blanket forts or circuit boards, produced community theatre or mixed media art installation, tell us: what have you invented, engineered, created or designed?’

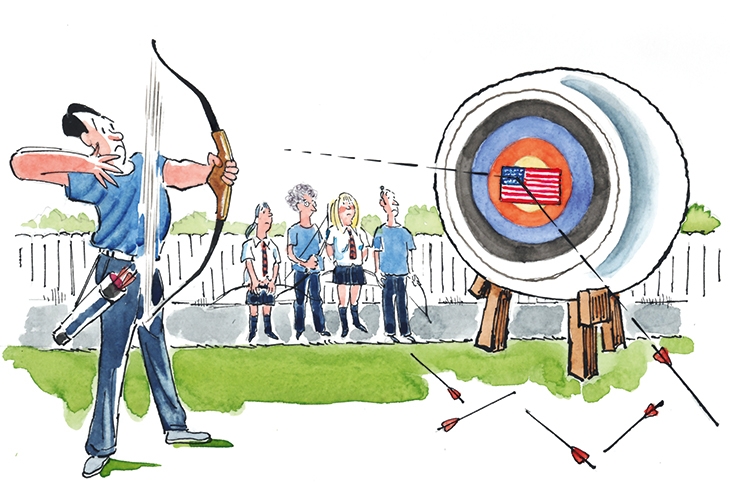

It’s enough to make some of us cower in a corner under a blanket fort. So, why the longing to get in? What makes them so attractive? Well, it’s partly that truly motivated students relish a challenge, like to pitch themselves against the near-impossible and see if they can break through the impenetrable wall. (Some admissions statistics from last year: 39,506 applied to Harvard and 2,056 won places — 5.2 per cent; 32,900 applied to Yale and 2,272 got in — 6.9 per cent. The Oxbridge admissions rate is about 20-25 per cent.)

There are other reasons. In this age when it’s the norm for motivated teenagers to get 12 A*s at GCSE, US universities appeal to the legions of successful all-rounders who are good at the sciences and English, maths and languages, but also fancy a taste of psychology and computer sciences. For the first two years, you do about six subjects and don’t have to narrow down to your ‘major’ until the third year. Many students like the idea of a ‘liberal arts’ college, where you study a wide variety of civilising subjects. Mary Breen, headmistress of St Mary’s, Ascot, which gets five or six students into US universities each year, cites this ‘not having to specialise too early’ as a major attraction for her girls.

But there’s something more seductive: a sense that these American private universities — not only the Ivy League ones such as Harvard, Yale, Princeton and Brown, but other high-ranking ones such as Middlebury, Amherst, Williams, Georgetown, Tufts, Pomona, Pitzer, Carlton — are sumptuous, educational Gardens of Eden, with beautiful, well-tended grounds, superb facilities and an incomparable sense of community, so that anyone going there will make friends for life with a dazzling group of international high-achievers after bonding on a campus for four blissful years, going out for sushi and decorating their shared dorms for Halloween.

Nina Barrengos, another London-based specialist on US university admissions, tells me: ‘Some parents are sceptical about their children applying to those less-well-known colleges. They say, “I’ll pay for you to go to Harvard but not to go to a school in the middle of nowhere I’ve never heard of.”

‘But some of those less well-known schools are fabulous places with astonishing access to professors and wonderful opportunities for paid internships during the vacations.’

She stresses there are 2,000 US universities against around 130 British ones, which means that the ‘top-tier swath’ is much wider. Do not scoff at somewhere like Middlebury College in Vermont, is her advice. Go and look at it and be converted.

Should students apply to US and UK universities simultaneously? Most schools advise against it, especially if you’re applying from the upper sixth form when you’re also busy preparing for A-levels or the International Baccalaureate. The American process will take up all your free time. But I spoke to one highly academic student who applied to 12 US universities last year, was not successful, and now rather wishes he had also tried Oxbridge or other UK options. The application process, and the slow drip-drip of US rejections, was so long and drawn out that he was sitting by his computer waiting for news from November to April. This year he’s planning to apply again — to universities in Britain, Canada and the US.

So if you, or your child, are aiming for the American university experience, then brace yourself. It’s a long, hard struggle.

Comments