I have remarked here before about our era’s tendency to accept election results if your side wins but to reject them if they lose. Happily in the UK there is no significant body of opinion which believes that Jeremy Corbyn won the 2019 election. True, there are a few Momentum loons who still think that Corbyn would have won had the Tories not somehow got more votes. But even among the most diehard Momentum-ites few actually come up with stories of ballot rigging, high-level corruption and more.

Still, our country is not immune to the ‘I only accept the results if my side wins’ tendency. After all, we had Carole Cadwalladr and others insisting for years that the Kremlin had somehow mysteriously manipulated the 2016 Brexit vote. And I must say that after hating them for wasting our time, I have come to pity these obsessives. They have deprived themselves of one of the most important opportunities that elections give people – which is not just the opportunity to get your way, but the opportunity to learn why you didn’t.

Having lost in 2019, the Labour party recalibrated, appointing Keir Starmer to lead it into a more centrist direction. Imagine what good might have occurred in the past five years if the people who pretended that Brexit was somehow manipulated had likewise accepted the vote as a genuine expression of the public’s well-formed sentiments about the EU. Imagine if the EU had been able to accept the same, recognised where it itself had overreached and managed to course-correct accordingly. The fact that people as high up as the European Commission consoled themselves with lies about the reason for the vote is, in the end, to their disadvantage more than ours.

Elsewhere in the world the tendency is more pronounced. Obviously you have the case of the United States, where it is becoming almost impossible to agree on who has won a particular election. A majority of Republican voters still believe that Joe Biden did not win the 2020 election, meaning that they have not been able to have the reckoning over why a small but significant swing of voters (white men, as it happens) were put off by Donald Trump. It is to the Republicans’ detriment that they cannot make this realisation, just as it was to the Democrats’ detriment that they could not accept that Trump won in 2016. From the week after that election Hillary Clinton pushed a Russia conspiracy as crazy as anything Cadwalladr came up with. And as lacking in evidence.

The Democrats never came to terms with the facts that 2016 was trying to tell them. And the Republicans have not come to terms with what 2020 might have told them, setting themselves up for a fine old pickle after November’s midterms. After all, the Republicans are expected to do well in those elections, possibly taking both houses. And how will they rationalise things at that moment? ‘2020 was a steal,’ they will keep saying, ‘but 2022 was not.’ In other words they will have to pretend that the great vote-rigging machine only grinds into gears every four years, but sits out the midterms. Although perhaps the Democrats will take this as their turn to denounce the midterms as a fraud.

The past week offered a further example with the re-election of Viktor Orban in Hungary. Orban collects more enemies than most leaders, and is the nonpareil at winding up a certain type of centrist or leftist. His government is avowedly post-liberal, he institutes policies which put Hungary first, and he has attitudes about teaching gender ideology in schools which would displease Stonewall.

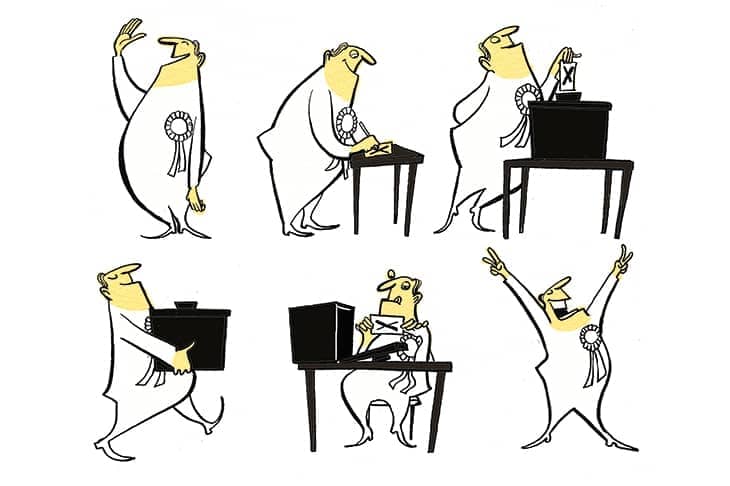

Elections give people not just the opportunity to get your way, but the opportunity to learn why you didn’t

But he has been elected to power four times, again this week with a thumping margin of victory. Against him this time was an alliance of six opposition parties who united in trying to take Orban out. These parties ranged from the Hungarian socialist party to Jobbik, which was until recently rightly described as a fascist party. Jobbik has realised that the old uniform-donning and goose-stepping does not please the average Hungarian voter and so has toned it down a bit of late. But still, it is fair to say that the anti-Orban alliance ranged from communists to fascists. Making Orban the moderate, as it happens.

And he beat them. He beat them all. But did his international opponents accept that? Did they hell. On Twitter the writer Yascha Mounk denounced the elections as ‘dubiously free and barely fair’. The Daily Telegraph called Orban ‘Kremlin-backed’. And the writer Anne Applebaum gnomically declared that ‘It’s easier to win elections if you cheat.’

That is certainly the case. Look at how the Democrats and the Democrat-supporting media cheated in America in 2020. They cheated so badly that they even boasted about it after the election, admitting that a coalition of media, tech people and democrat operatives had worked in the shadows to encourage a Biden victory. If you doubt that, consider the way that Big Tech censored America’s oldest paper, the New York Post, when it ran the bombshell revelations about Hunter Biden’s laptop and the first family’s corruption (in Ukraine among other places). The New York Times and Washington Post now admit that the contents of the laptop were real. Though there is still no apology from the dozens of members of the intelligence community who claimed that the Post’s story was, guess what, Russian disinformation.

So yes, you can do a lot if you have most of the press on your side. As the Democrats do in the US. And as Orban does in Hungary. But the public do not vote as they do simply because a majority of the press tells them to. And anyone who thinks otherwise sadly overestimates the power of the press. Orban won, like Law and Justice in Poland, and Biden in the US, because he was more popular than his opponents. Ignore that and you deprive yourself of the chance to learn some lessons. Bang away about it and spread lies and smears, and strangely enough, in the name of defending democracy, you place a depth charge beneath it.

Comments