The government’s fealty to human rights law is not in doubt. Still, one might have hoped that the human rights lawyers who dominate this government – the Prime Minister, Sir Keir Starmer KC and the Attorney General, Lord Hermer KC – would handle human rights law effectively, distinguishing weak from strong arguments and making a reasonable case for our national interest. The unfolding debacle in relation to cession of the Chagos Islands shows that this is not so. In bending heaven and earth to agree a treaty of cession with Mauritius before the looming change of political leadership in the United States, the government seems to have undersold the UK’s existing legal position, which is in fact strong, and to be fretful about litigation yet to come, to which the UK does not have to consent.

The Supreme Court badly misread the 1972 legislation

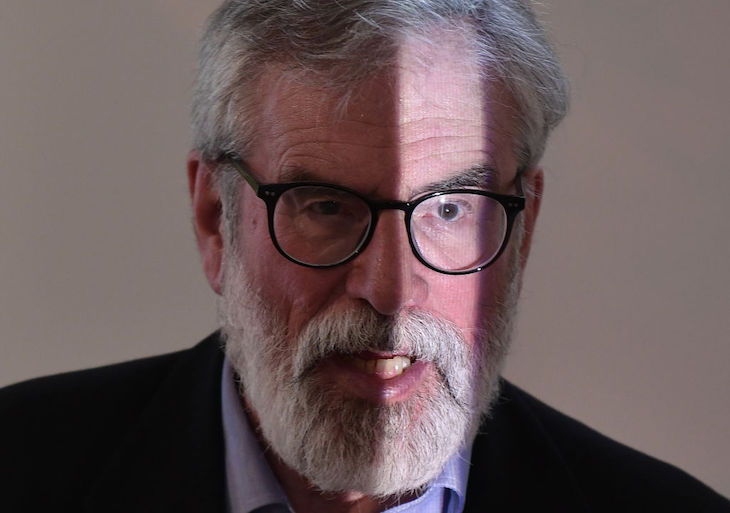

Another recent government decision betrays the same hyper-legalist disposition, sacrificing good legal arguments and practical considerations on the altar of polite legal opinion. However, this decision has attracted much less attention to date. What the government now proposes to do is to use its powers under the Human Rights Act 1998 to repeal legislation, enacted in 2023, that prevents Gerry Adams and hundreds of others claiming “compensation” from the British taxpayer for having been detained in the 1970s for suspected involvement in terrorism.

The background is this. In May 2020, the Supreme Court decided to allow Gerry Adams’s appeal against his 1975 conviction for attempting to escape from lawful custody. Adams had been detained under legislation enacted in 1972. The Supreme Court ruled that his detention was unlawful because it had begun with a decision that had been made by the Minister of State for Northern Ireland, rather than by the Secretary of State personally.

In reaching this conclusion, the Supreme Court badly misread the 1972 legislation. In particular, the Supreme Court wrongly downplayed the fundamental Carltona principle, which provides that a power conferred on the Secretary of State may be exercised by others on his behalf. The obvious risk was that the Supreme Court’s misinterpretation of the 1972 legislation, and its mishandling of the Carltona principle, would cause widespread legal uncertainty.

The Supreme Court’s judgment also had a more direct effect. It provided that Gerry Adams had been unlawfully detained in the 1970s, which opened the door to him seeking compensation for wrongful conviction and to bring a claim for damages for false imprisonment. It also enabled any other person detained in the 1970s in the same way to initiate legal proceedings. In the aftermath of the 2020 judgment, hundreds of claims were filed.

Happily, Parliament decided to do something about this. In 2023, the Northern Ireland Troubles (Legacy and Reconciliation) Bill was amended to reverse the Supreme Court’s judgment, not to reinstate Gerry Adams’s conviction, but rather to restore the law as it stood between 1972 and 2020. The point was, first, to make clear that the Supreme Court had misunderstood the legislation and that its analysis and application of the Carltona principle should not be followed; and second, to stop Adams and others being paid public money on the basis of a mistaken judgment.

The overall Bill was highly controversial, but these amendments were not. They were adopted without division; the Labour Party, then in Opposition, supported them too. But now the Labour government is all set to change them. Why? The answer is that in February last year a single High Court judge declared this part of the Northern Ireland Troubles Act 2023 incompatible with Convention rights. The judge reasoned that Parliament had acted unfairly in reversing the Supreme Court’s judgment and that Parliament had no good reason for legislating in this way.

In a new paper for Policy Exchange, Sir Stephen Laws and I show that the High Court’s declaration of incompatibility was entirely unwarranted. The High Court misunderstood Parliament’s intentions and failed to grapple with the damaging consequences of the Supreme Court’s 2020 judgment, which Parliament had very good reason to try to avert.

Our critical analysis of the judgment has been publicly backed by some of the UK’s leading judges, lawyers and statesmen – including Lord Hope, the former Deputy President of the Supreme Court, Lord Etherton, former Master of the Rolls, Lord Butler, former Cabinet Secretary, and Lord Macdonald KC, former Director of Public Prosecutions.

The High Court made five declarations of incompatibility in its February 2024 judgment, only one of which concerned this part of the 2023 Act. The then government appealed to the Court of Appeal, but in July 2024, shortly after the general election, the new government abandoned the appeal against all five declarations, with the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland saying that this “underlines the government’s absolute commitment to the Human Rights Act”.

This statement takes deference to judicial authority to dizzying new heights. Exercising a right of appeal is obviously not some kind of a failure of commitment to the Human Rights Act. What seems to have happened is that the government has taken the five declarations as one, and has failed to think about this particular declaration, which concerns legislation that it supported.

This statement takes deference to judicial authority to dizzying new heights

The government has now exercised its powers under section 10 of the Human Rights Act and has begun the process of repealing this part of the 2023 Act by ministerial order. It has tabled a draft Remedial Order before Parliament. The Joint Committee on Human Rights is reviewing the order now, after which each House of Parliament will have its say.

But the opportunities for Parliament to debate this proposed law change are sharply limited by the form in which the change is set to be made. The Remedial Order cannot be amended but can only be accepted or rejected. Many parliamentarians may be content with the government’s response to the other declarations, but not with its response to this declaration in particular.

The government has promised to bring forward a new bill that will repeal and replace the whole 2023 Act. The proper course of action would be for the government to amend its draft Remedial Order, removing its proposal to change the law to revive claims for compensation by at least 300-400 people, like Adams, whose detention half a century ago was, we believe, perfectly lawful.

The sheer irresponsibility of the government’s approach is made clear by its assertion that there is no need for an impact assessment “because this Order is required to implement a court judgement [sic]”. In fact, the government chose to abandon a strong appeal and to exercise its ministerial powers to reverse Parliament’s reasonable decision to restore legal certainty and prevent unjustified payments. Parliamentarians and the public should not lightly accept this.

Katy Balls, Michael Gove and Kate Andrews discuss the issue of compensation for Gerry Adams on the latest Coffee House Shots podcast:

Comments