When I was a small boy, I had a favourite book: The Magic Faraway Tree, by Enid Blyton. Given that my own family life not was not untroubled, the story of how a bunch of regular kids travel, via this wonderful tree, to a sequence of fantastical places, where they meet lovable characters like the Saucepan Man, Moon-Face, and Silky the Fairy, seemed to embody a childish version of heaven. An escape, and a Utopia.

Yesterday, many decades after reading Enid Blyton under the bedcovers, I encountered the opposite of the Magic Faraway Tree. A tree that is still faraway in time and conception (and growing evermore so), but a tree that is all too real, and very definitely not magical.

The tree is in a quiet, sunstruck park, lost in a grimy exurb of the Cambodian capital, Phnom Penh. The tree is decorated with hundreds of bracelets and trinkets, with the occasional teddy bear and kiddies’ drink – poignantly Blyton-esque touches, perhaps.

But if you look close at the bark of this tree, you can see tell-tale abrasions: chops, scars, bruises. These blemishes mark the places where peasant soldiers would swing screaming children against the tree, smashing their skulls to pulp. This was done, quite deliberately, in front of their naked, wailing and soon-to-be-murdered mothers. Because this is the infamous Baby Bashing Tree, in the Khmer Rouge Killing Fields of Choeung Ek.

This tree is obviously important, historically, but it also has some importance for me, personally. Because, on my previous visit to Cambodia, in 2009, I encountered the man who ran these Killing Fields of Choeung Ek, as well as the Khmer Rouge Prison of Tuol Sleng, in the middle of Phnom Penh. Tuol Sleng is where the chosen victims of the KR were tortured with surreal cruelty to extract lunatic confessions, before they were finally driven out of town to Choeung Ek, to be bludgeoned to death with axes, hammers, crowbars and trees – to save money on bullets.

I was in Cambodia for the most trivial of reasons: to write for a UK magazine about the wildly exotic foods of southeast Asia, and to eat them (if I could). However, when I landed in Phnom Penh I heard that a well-known Khmer Rouge apparatchik, Comrade Duch (real name: Kaing Guek Eav) was on trial by the UN. As I’d long had an interest in the bewildering, nihilistic horrors of the Khmer Rouge, led by the infamous Pol Pot and his henchmen, I used my journalistic credentials to get a pass to the trial.

It is an experience that I have never forgotten. The trial was conducted in a large, specially adapted auditorium on the outskirts of the city. Imagine a big Nordic concert hall, but instead of a jazz trio onstage, there is a small, wizened, croaky old man – Duch himself – surrounded by a team of officious lawyers.

The auditorium was jammed – with some press, but mainly with ordinary Cambodians, who came, day after day, quite desperate to hear an ‘explanation’ for the terror that befell them in the Khmer Rouge years, 1975-79. Much of the evidence I heard that day was technical, dry, difficult to understand, but one moment chilled me. Duch was asked if he had ‘any regrets for his time in charge of the Killing Fields.’ He replied, flatly and calmly, ‘I am sorry for the babies we smashed against trees. And so forth.’

Villages were devoid of people over 45 – because everyone that age was dead

At that point I heard a noise I had never heard before, and hope never to hear again. It was the like the rush of a sudden, melancholy tide, yet carried in the air. It was the sound of several thousand people stifling their sobs. It was the sound of almost everyone crying for their dead children.

I was duly shaken. I drank a lot of gin in the Foreign Correspondents’ Club by the Tonle Sap river. I went to hideous Tuol Sleng – where I saw blood sprayed on the ceilings, possibly from the Khmer Rouge’s human vivisections – but I did not have time, on that visit, for Choeung Ek with its tree. I had a job to do. Eating weird things.

Yet even as I went around Cambodia, doing this absurd task, I encountered the reality of post-Khmer Rouge Cambodia, sometimes gutting, sometimes surreal. Cab drivers would casually say, ‘Oh I lost my brother to the Khmer Rouge. And my sister. And my mother, father, niece and uncle.’ Villages were devoid of people over 45 – because everyone that age was dead.

Even the mad food sometimes came with terrible backstories. Such as the tarantulas roasted in garlic and soup-powder, and famously served in the small town of Skuon.

Unsurprisingly, roasted tarantulas are disgusting (or they were to me). So why do the people of Skuon eat them? One theory is that they were all so hungry, under the many catastrophic famines of the Khmer Rouge, they ate the only living thing left. Horrible big black spiders, endemic in the neighbourhood. And thus the Tarantulas of Skuon became a delicacy.

After my tarantula moment, I yielded to my interest in Khmer Rouge history. I went to some more ‘famous’ Khmer Rouge sites (there are killing fields throughout the country). I even made a long, tricky, two day pilgrimage to the most remote Khmer Rouge site of all: Anlong Veng, in Cambodia’s far northwest, in thick jungle near the Thai border. This is where the Khmer Rouge regime continued, in stunted form, after they were driven from most of the country by the invading Vietnamese in 1979.

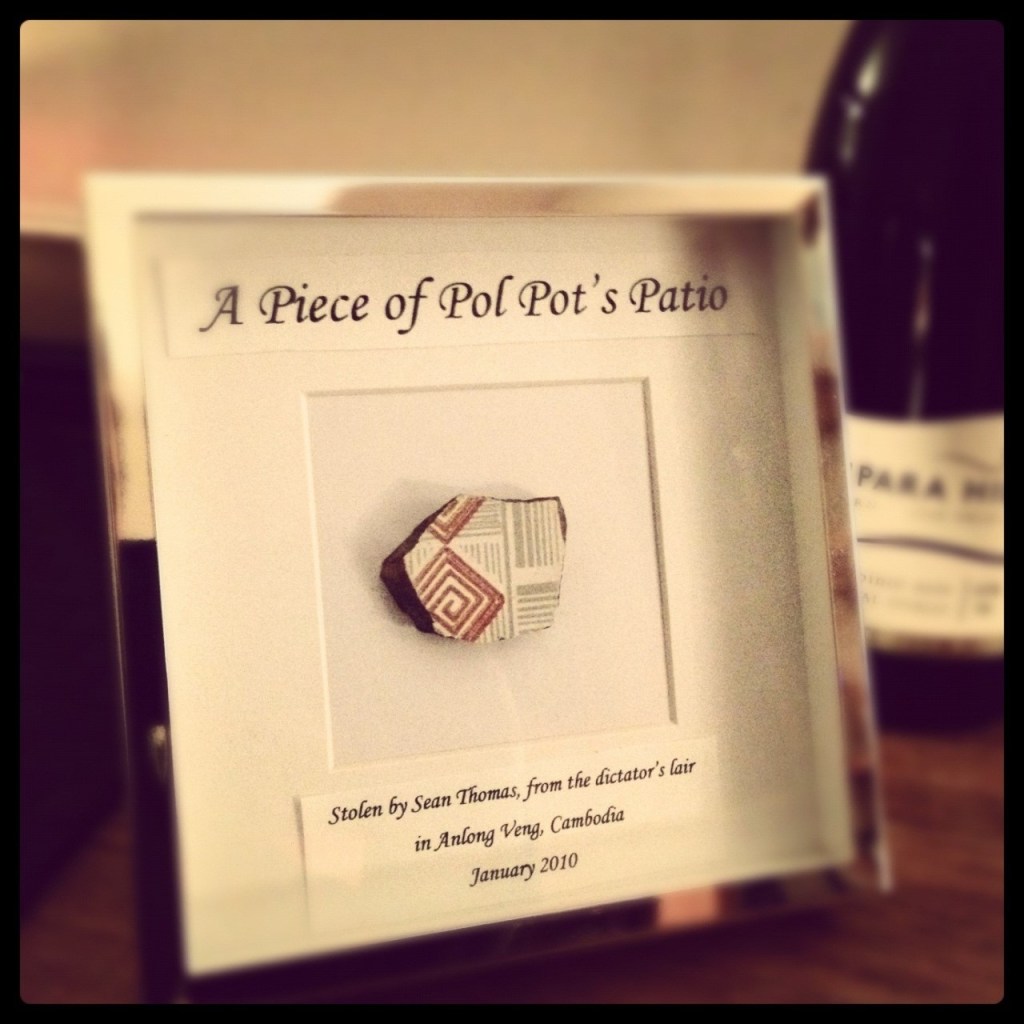

I gazed at the Khmer Rouge’s very last truck. I toured the grim concrete bungalow of Pol Pot’s acolyte, Ta Mok, alias ‘The Butcher’. And eventually I found the last home of Pol Pot himself. It is a suitably ugly redbrick bunker, in a scruffy jungle clearing. I stole a piece of Pol Pot’s patio, as a macabre souvenir (sorry). Then my guide – i.e. a local with a moped, and a bit of English – showed me a spirit house, near Pol Pot’s terminal lair, a kind of shrine to this evil man. Nearby was Pol Pot’s grave, decorated with food, coins, cans of Red Bull. The guide told me that Thais would come across the border, and make offerings to the infamously atheist Pol Pot, in the hope that his spirit would bring them luck in the lottery.

I left Cambodia soon after, but my interest in the Khmer Rouge persisted. In Bangkok I met Vann Nath, one of the estimated 12 survivors of the 20,000 people who went through Tuol Sleng (he survived because he was a portrait painter, and the Khmer Rouge bigwigs were vain). I met Roland Neveu, one of the few brave photographers who was in Phnom Penh, on the day the menacingly silent KR peasant squaddies entered the city and drove its 2 million inhabitants into the countryside. A self-described ‘soixante huitard’, Roland told me that in the space of 24 hours he went from quite passionate hope for the Marxist revolution, to grave and horrified doubt.

However, as my interest in the Khmer Rouge has persisted, the rest of the world has not been anywhere near as intrigued. Several times in the last decade I have met intelligent people with shockingly meagre knowledge of the Killing Fields, Tuol Sleng, and the Khmer Rouge. Last month, in the USA, I met a young, Oxford-educated woman who actually used the words: ‘who was Pol Pot?’ The history of this regime is being lost to humanity.

Here, then, is a brief reminder of the Khmer Rouge, and what they did. And, in the end, why it really matters. Why Pol Pot must not ever be forgotten.

In 1975, the ancient monarchy of Cambodia was roiled by the troubles shaking all of Indochina. Vietnam was at the end of its long war for independence, led by the communist Viet Cong. The USA was bombing, often with bestial inaccuracy, Vietnam’s neighbours like Laos and Cambodia (used as supply lines by the VC). Cambodia was thus semi-involved in the war.

At the same time, a groupuscule of Paris-educated Cambodian ultra-Maoists, the Khmer Rouge, was rising to power. They started by radicalising and arming the peasantry, firing them with violent passion. Eventually they seized the capital (that terrible day witnessed by Roland Neveu). They then set about enforcing their crazed belief in an agrarian paradise, with everyone labouring like oxen in the rice-fields. A Maoist autarky. A place without money (they literally blew up the national bank, scattering now-worthless banknotes into the jacaranda trees). A place without religion, hierarchy, social class, intellectuals.

To do this, they killed all the middle classes. Everyone. If you had an education, you were killed. If you spoke a foreign language, you were killed. If you were a monk, a teacher, a lawyer, you were killed. People wearing spectacles were killed. Anyone who could dance was killed; ancient and exquisite Cambodian dance was a tradition handed on orally and practically – this meant that the nation of Cambodia forgot how to dance.

When the KR ran out of obvious bourgeoisie to kill, they killed each other. For any reason. People caught with snails in their pockets were killed. People were killed for having sex, or being happy, or laughing. In the end it is estimated the Khmer Rouge slaughtered about 2-3 million people in a population of 8 million. Cambodia is the nation that crucified itself.

Why? Why was this regime so mad? This is the question many have asked. After this latest visit, finally going to Choeung Ek, I think I perhaps have an answer. In his fine, troubling book – The Elimination – about his interviews with Duch, Khmer Rouge survivor Rithy Panh quotes Duch saying that in his world ‘there is no place for the individual’, and ‘beauty is an obstacle’.

This is important because it reveals the insane yet inexorable logic of the Khmer Rouge. If Marxism means enforced equality, its ultimate endpoint is this. Individuals cannot be ‘allowed’ as they might be ‘different’, they might laugh or be happy, unlike others. Beauty – physical, artistic, sexual, spiritual, intellectual – must likewise be ruthlessly extinguished, because it too prevents a Marxist Utopia. Beauty is unfair. It must be eliminated.

Does this matter? Yes, because we live in a time when kids think Marxism is cool again. When self-confessed Marxist Jeremy Corbyn is seen as an amusing old uncle.

This cannot stand. Just as we teach children about Hitler, the ne plus ultra of rightwing ethno-nationalism, they need to be taught about the ultimate leftwing cruelties of the Khmer Rouge, and the horrors of Pol Pot. That is to say: we need to take young people from the cocktail bars of modern Phnom Penh, down that long, littery suburban road, to a sunlit stupa full of human skulls, to trenches gleaming with human teeth, to the place where babies were smashed to death, in the name of Karl Marx and Chairman Mao, the Saucepan Man and Moon-Face of communism. We need to show them the Satanic Faraway Tree.

Comments