Melissa Kite has narrated this article for you to listen to.

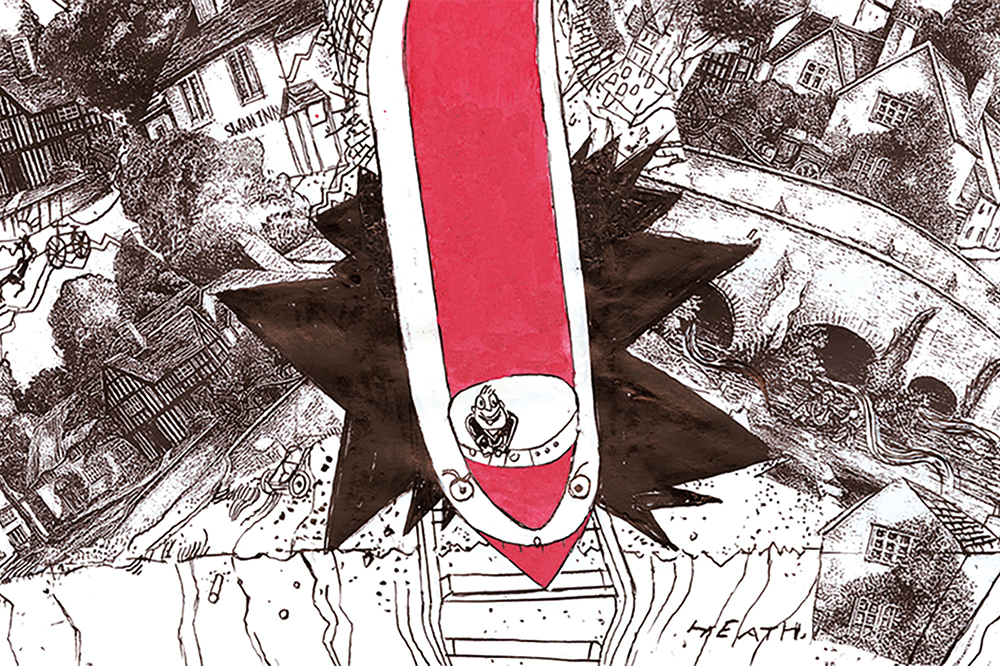

When I drive to see my parents in the once-peaceful farming country where I grew up, it is a strange, bittersweet experience. The car journey takes me through places I ought to recognise but I don’t any more, because the green fields of Warwickshire, the villages and the farms, are scarred by the tortuous works of HS2.

The distinctive red earth is laid bare for mile upon mile as the bulldozers do their worst. Rows of cottages and entire villages lie deserted, testimony to the billions already spent. As I drive along the main Banbury to Coventry road, I see mountains of earth piled high as flyovers take shape. I stare at this curiously outdated project – old hat both in terms of the controversy and the purpose it was meant to have. It seems to me that the works advance only about a few inches every time I drive up there.

Crackley Crescent became Area 18 in the HS2 plans

A high-speed line has, for many years, been yesterday’s answer to yesterday’s problem. It was outmoded when the Tories backed the idea at their 2008 conference: the speedy trains to Manchester and Leeds would cost just £16 billion, it was said, and be ready by 2027. That money has been spent, but not an inch of track has been laid. The budget is closer to £100 billion and the deadline is some time in the 2040s.

But it’s not just that. Lockdown accelerated home-working, so commuter trains from Manchester and Leeds are already arriving in London full of empty seats. It is so old-fashioned and pointless – the idea of paying billions so businessmen can get to a meeting a few minutes quicker – that the main puzzle is why Rishi Sunak has not just cut his losses and called the whole thing off, rather than half of it, from Birmingham northwards. His alternative to that – a massive list of road and rail upgrades – was a trade-off that should have been made years ago.

London to Birmingham is fast enough already – under 80 minutes every time I have done it – and it has always seemed folly to argue that £50 billion or indeed £100 billion would be well spent making that journey shorter by less than half an hour.

A Japanese-style bullet train might have been a good idea 20 years ago when travel time was dead time. But now that you can easily work on a train, who is going to pay £200 or more for a high-speed train ticket just so that you can get from London to Birmingham ten minutes quicker?

My parents were not close enough to the line to be automatically bought out. Only those within 60 metres of the proposed 225mph trains were compensated without a fight. The three-bedroom semi I grew up in, one of a dozen in a row surrounded by fields, rather sweetly called Crackley Crescent, was 200 metres from the line, and because it was flood plain, a massive feat of engineering was planned to get the railway across their road. The farm opposite was carved in two and Crackley Crescent became Area 18 in the HS2 plans.

A leading law firm took on my parents’ case, and I found myself sitting in front of a House of Commons select committee giving evidence about their plight as we fought to persuade HS2 Ltd that they needed to be compensated, that they could not be expected to live the latter part of their lives cut off from the nearby towns and services by endless roadworks, watching the surroundings they love being bulldozed around them.

My parents were treated abominably. At one point the union leader Bob Crow suggested people like them should stop worrying about their ‘lawns’, as though anyone whose home was lost was just a rich Nimby. I’d like to see George Osborne (or Lord Adonis, who championed HS2 for Labour) wake up to find his home was next to a high-speed rail overpass and be happy about it.

The HS2 lawyers tied us up in mind-bending bureaucracy and waited until the very last moment, when my parents were packed up and ready to move to a new home further away from the line, to suddenly drop their offer. They had the cheek to tell me that this was in order to get the best deal for the British taxpayer. I sent an email back pointing out that my parents are the British taxpayer.

The wooded landscape at the back of the house where I grew up was once teeming with wildlife. Trees were cut down during breeding season. Ancient woodland was desecrated. There is hardly anything recognisable left of that natural landscape. Hundreds of acres of beauty are gone, and for what? If a vital new economic artery had been created – say, a power line that would halve energy bills – then fair enough. But this is all about shaving ten or 20 minutes off a train journey for a fantasy group of business people who, it is imagined, are suddenly going to come off Zoom and go to meet each other in an office.

As they began the felling, some idiots from the local council erected a modern sculpture of a tree, made of wood, complete with a plaque about biodiversity. You could not make this stuff up. Joni Mitchell sang many years ago about a time when they would cut down all the trees and put them in a tree museum. Now, courtesy of HS2, that really is happening.

What a terrible waste of years of struggle: not just for my family, but for all the people whose lives have been blighted. What an almighty con against the taxpayers whose money could and should have been spent on repairing roads, school buildings or building an east-west railway that the people in the north of England might actually use. And what a waste of all that beautiful countryside that is gone for ever; what a kick in the teeth for those communities where life will never be the same again.

Comments