Il Turco in Italia

Royal Opera, in rep until 19 April

Commentators on Rossini’s Il Turco in Italia tend to take a defensive line, comparing its absence from the repertoire for many decades with that of Così fan tutte, and even comparing the two works directly, as well as pointing out that Mozart’s great opera was playing in Milan at the time that Rossini was composing Turco. And Gregory Dart, in his essay in the programme of the Royal Opera’s production, first seen in 2005 and now revived for the first time, quotes Stendhal, a passionate admirer of both composers, writing that ‘Rossini is always amusing, Mozart never; Mozart is like a mistress who is always serious and often sad, but whose very sadness is a fascination, discovering ever deeper springs of love’. One can wholeheartedly agree with that second sentence, while being astonished at the falsity of the first. If it’s not simple slapstick that you want — and Die Zauberflöte will provide some of that — where are there more amusing things than the Count’s unveiling of Cherubino in Act I of Figaro, or Susanna’s pert stepping forth from the closet in Act II? It’s hard to credit that Stendhal, supreme master of shades of irony and of some comedy, could have been so crass, less hard to credit that many writers on opera have followed him.

Così is of course a special case, in that once one has penetrated its superficial comic effects — the ‘Albanians’, Despina’s disguises — it makes you wince at least as much as you smile, yet the wincing and smiling are inextricable. There are no such tangles in Rossini, whether in Turco or in any of his other comic operas. The nearest one comes to that is in La Cenerentola, where the pathos of Cinderella doesn’t completely hide an element of malice in her character. But Turco is a pure comedy of situation, not at all one of character. Anyone arriving at the Royal Opera without knowing the plot, and therefore needing to read the summary in the programme, needs a generous provision of time, for it goes on for three closely printed pages, more than any other I can remember.

The best operas, with a few exceptions, can be summarised much more briefly than that. Turco only keeps going thanks to the hypermanic rate of incident. That is Rossini’s forte, but in the finest of his comic operas, before the giddy series of events is fully launched, the characters are defined in arias that give vital information about their central motives and ambitions. Turco is not at all like that. All the commentators also agree that it is an opera of ensembles rather than of arias, and that is true to such a degree that one only distinguishes between them on the basis of their clothes, station, gender and ‘ethnicity’.

So what is required for a satisfactory — because mildly involving — production of Turco are singers with marked personalities. That is especially true of Fiorilla, the heroine who leads most of the rest of the cast such a dance. In 2005 she was played by Cecilia Bartoli, an excellent team member, and, whatever one thinks of her vocal personality, an unmistakable star presence. The same, clearly, was true of Callas’s great recording, though it was ‘inauthentic’. Unfortunately, it isn’t true of Aleksandra Kurzak. She has many delightful qualities, including her appearance and a fairly lovely voice, and she can negotiate most of Rossini’s vocal demands. But she is not an outstanding personality onstage, and it doesn’t look as if directors Leiser and Caurier have tried to make her one. She is so good a team member that she merges with the rest.

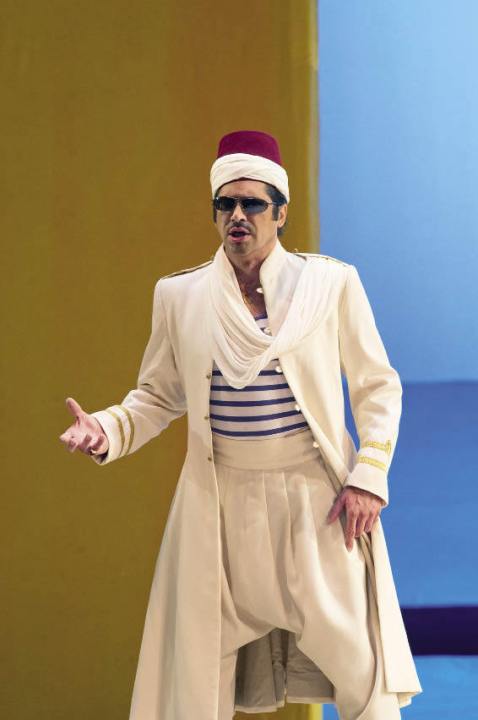

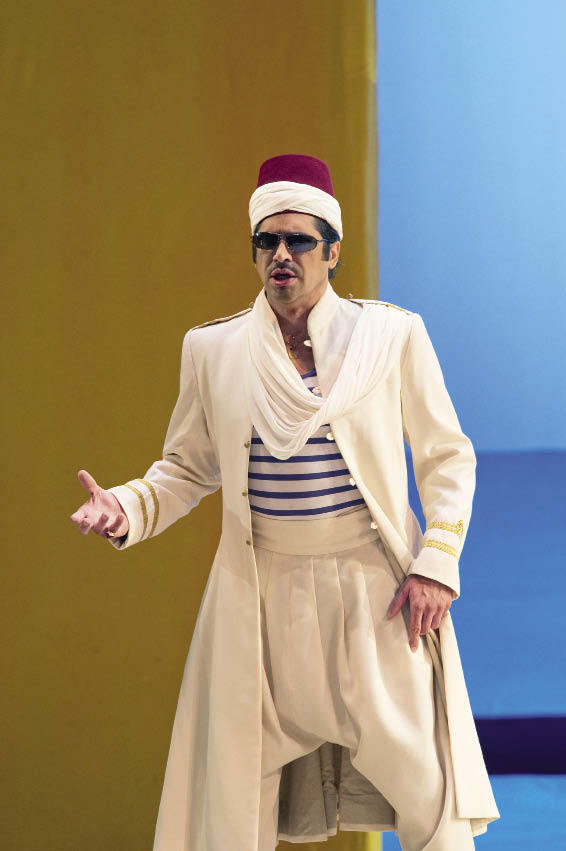

The other female character, Zaida, played by Leah-Marian Jones, is at least as vivid. The one strong stage presence is that of Alessandro Corbelli, who is by no means content to rest on his well-earned laurels as a comic bass: he individuates every role he sings, and is a study in himself. Thomas Allen, in the curious role of the Poet, who is more or less responsible for the opera’s taking the course it does — something in between Da Ponte and Don Alfonso in Così — is still unignorable when on stage, but his voice varies between the mellifluous and the unreliable. The crucial male is the Selim, and though Ildebrando D’Arcangelo looks the part, with glamour to spare, his voice is not a strikingly individual one. Rather better is the Don Narciso of Colin Lee, a swaggering 1960s figure, with the same kind of voice as Juan Diego Florez but one which is to me more agreeable, since it involves no yelps. Maurizio Benini keeps things spinning along, and the colourful settings are inoffensive, though no help. It makes for one of those unobjectionable evenings which don’t seem to have a lot of point, which at least provides a contrast with all those objectionable evenings at the Royal Opera that we have had to endure this season.

Comments