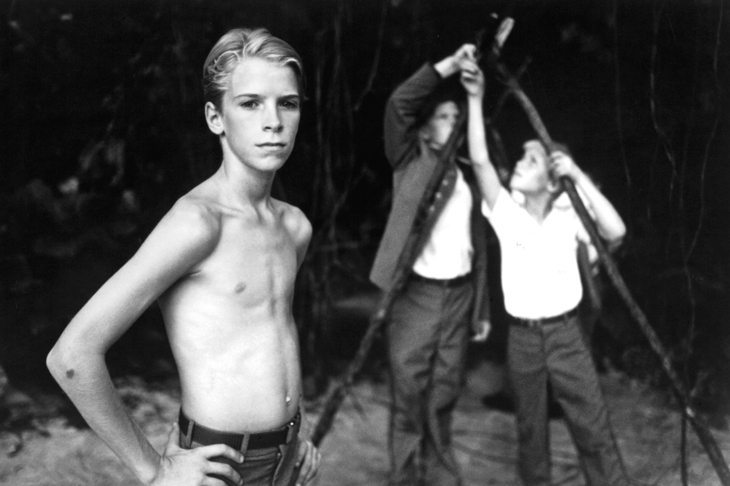

There’s a scene in Lord of the Flies, William Golding’s masterpiece about the collapse of western civilisation, in which a particularly sadistic boy named Roger starts to throw stones at a weaker, younger lad called Henry. Yet when he tries to hurt the boy, he finds he cannot do it. ‘Roger gathered a handful of stones and began to throw them,’ writes Golding. ‘Yet there was a space round Henry, perhaps six yards in diameter, into which he dare not throw. Here, invisible yet strong, was the taboo of the old life.’

Golding attributes this six-yard forcefield to civilisation. It’s the legacy of the various authorities Roger has been conditioned to respect — parents, school, policemen, the law, etc. And as anyone who’s read the book will know, eventually this protective barrier collapses. The theme of Lord of the Flies is that the savage constrained by the rules of civilised society is never far from the surface. The rule of law and relatively low rates of violence we take for granted in countries like the UK could easily collapse, unleashing a Hobbesian dystopia, a war of all against all.

Some believe we’re witnessing the beginnings of this breakdown in British politics, particularly with the battle over Brexit intensifying, and cite the verbal assault of Anna Soubry by James Goddard as evidence. It is a commonplace among Remainers that the referendum ‘unleashed demons’ — originally David Cameron’s phrase, but taken up by many in the last couple of years, including Craig Oliver, who adapted it for the title of his book about why Remain lost.

I’ve never been convinced by this. To me, it’s always smacked of contempt for ordinary people. It’s part of a larger, anti-democratic narrative in which the electorate are too easily swayed by the emotional rhetoric of right-wing demagogues and ‘fake news’ on social media. They should not be trusted with important decisions about matters they cannot possibly understand, like the pros and cons of EU membership. Best if those questions are left to the experts.

In fact, there’s precious little evidence that ‘demons’ have been unleashed by the referendum. Yes, there was an uptick in reported ‘hate crimes’ in the immediate aftermath, but the definition is so nebulous — all that’s required is that someone, anyone, perceives the crime in question to be motivated by hostility to the group the victim belongs to — that it’s hard to set much store by the data. In fact, polling evidence shows that Britain has become less hostile to immigrants since 23 June 2016 and is now the most pro-immigration state in the EU. As Fraser Nelson has pointed out, the anti-immigration populism that has been making inroads in the rest of the EU hasn’t gained much purchase in the UK — at the last general election, the three mainstream parties polled more than 90 per cent of the votes. For what it’s worth, it also appears to have plateaued in Europe, with nationalist parties winning a median of just 13 per cent of votes in elections last year.

Apart from the lack of evidence, the other problem with the ‘demons’ hypothesis is that it casts the people who voted for Brexit and would like us to make a clean break with the EU as mouth-breathing Morlocks and the Remainers as the large-brained Eloi. I have some sympathy for what Anna Soubry has had to endure at the hands of anti-Brexit protestors, but she’s hardly a model of calm, rational dialogue. Brendan O’Neill revealed that he had been subject to a foam-flecked barrage from the MP for Broxtow on the Sky News Politics Podcast, and I experienced a lesser version of that myself when I clashed with her on The Agenda, ITV’s version of Question Time. Turns out she doesn’t like it when you point out a majority of her constituents voted Leave. If there’s a lack of decorum in the Brexit debate, it surely affects both sides.

Perhaps the biggest problem with the idea that civility in public life is in decline is that it’s often used as part of a broader argument to restrict free speech. Advocates of ‘safe spaces’ and ‘trigger warnings’ in British universities always set out their stall by citing evidence that violent assaults on women and minorities are increasing. But when you drill down into their data, it usually turns out to be bogus. For instance, they are defining ‘violence’ to include ‘epistemic violence’, e.g. using the wrong gender pronoun to address a trans person. The truth is, those protective six yards that Golding identified are still very much intact and the norms of civilised society are more robust than he feared.

Comments