The Diary of Miss Idilia presents the reader with an unusual problem. The writing is entirely comprehensible, the tale it tells couldn’t be easier to follow. The tricky bit, though, comes with trying to work out what on earth the book is.

In 1851, 17-year-old Idilia Dubb was on holiday in the Rhineland with her middle-class Edinburgh family when one morning she disappeared. A lengthy search found nothing, and her parents returned home. Then, in 1860, workmen restoring Lahneck castle outside Coblenz discovered her remains at the top of a seemingly inaccessible tower. Near the body was Idilia’s diary, which recorded in tones of increasing anguish how she’d climbed up a wooden staircase, and how it had collapsed immediately afterwards, leaving her stranded without food, water or means of escape.

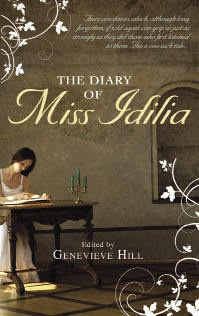

Despite widespread public interest, the Dubbs wouldn’t allow Idilia’s diary to be published — partly because it was so rude about them — and it eventually ended up the property of a private trust in Scotland, where it was recently tracked down by an American academic. Now, with Swedish and German translations already available, the original version, as edited at the time by Idilia’s friend, Genevieve Hill, finally makes its British debut…

Or at least that’s the story. Yet surely even the most credulous reader wouldn’t get too far here without smelling several large rats. In its full form, the diary tells not only of Idilia’s terrible last days, but of the whole holiday, beginning with the journey up the Rhine by steamer. No sooner have the Dubbs set off than Idilia has a dream that prefigures her later fate with eerie precision. Plenty of other foreshadowing devices then follow, of the kind more commonly found in, say, fiction.

More suspiciously still, the narrative is completely action-packed. Idilia narrowly escapes rape on a regular basis, and get entangled in at least three love triangles. When her younger sister falls overboard, one hunky suitor jumps in and saves the girl seconds before she’s sucked into the steam paddles. After Idilia dines ashore with the same man, Christian Bach, the couple miss the next sailing and take days to catch the boat up — getting into any number of neatly escalating scrapes, and causing Idilia to compare herself (accurately) to ‘the heroine in a romantic novel’.

So, could it be that Genevieve Hill made up the whole backstory, thereby fulfilling what we learn in an afterword was her dream of writing adventure stories? Well, maybe — except that much of the diary doesn’t feel all that Victorian. Christian’s face, Idilia tells us, ‘looked good enough to eat’, which is good news because ‘for seventeen years I have felt myself to be a loser’. Now, like many a chick-lit heroine after her, she can be herself at last. She can stop being ‘nice, boring Idilia’ and just have some fun with a man ‘who can make me laugh’. (She can also, apparently, coin the word ‘snooty’ 50 years before its first recorded use.)

Short Books convincingly claim to have no proof that The Diary of Miss Idilia is not what it seems — which is why they’re publishing it as straight non-fiction, with only a rather coy closing note that its ‘authenticity can never be entirely verified’. The result is both a genuine literary curiosity and, not least, a highly enjoyable read. (Amid all the implausibly gothic thrills, Idilia also serves up a pretty impressive travelogue.) Yet, whether these pleasures are enough to banish — or compensate for — the accompanying sense of being taken for a sucker will, I suspect, depend purely on the personality of the individual reader.

Comments