On the evening of 10 August 1996, I found myself lost in the grounds of a stately home in Hertfordshire, and very, very drunk. Everywhere I turned, there were men, mostly young men in bucket hats. They were all raucously singing, and they too were very drunk. Everyone was drunk.

It always felt like the Gallagher brothers were performatively baiting each other for show, like two camp old wrestlers trying to hype a crowd

Almost 30 years on, the Oasis concert at Knebworth is, what those working in marketing like to call, legendary. There has already been a commemorative album and documentary film – and now an Oasis reunion will see millions of people attempt to spend tens of millions of pounds to be able to attend re-creations of Knebworth next summer. But my memory of Knebworth ’96 is that of a nightmare. For me, it was the night when the 1990s dream died. It was my Altamont – except with lads from Stevenage singing along to ‘Wonderwall’, taking the place of knife-wielding Hells Angels, and plastic pints of Stella Artois standing in for LSD. Eventually, I threw up.

And this was a fitting critical response to the show. My lager-induced epiphany that night was that Oasis weren’t the saviours of rock ’n’ roll. They were – and there’s no other way of putting this as it’s the only technical term in the music criticism lexicon that accurately covers the meaning I’m trying to summon – shit. They had perpetrated an enormous confidence trick on seemingly everyone under 30 in Britain, including me.

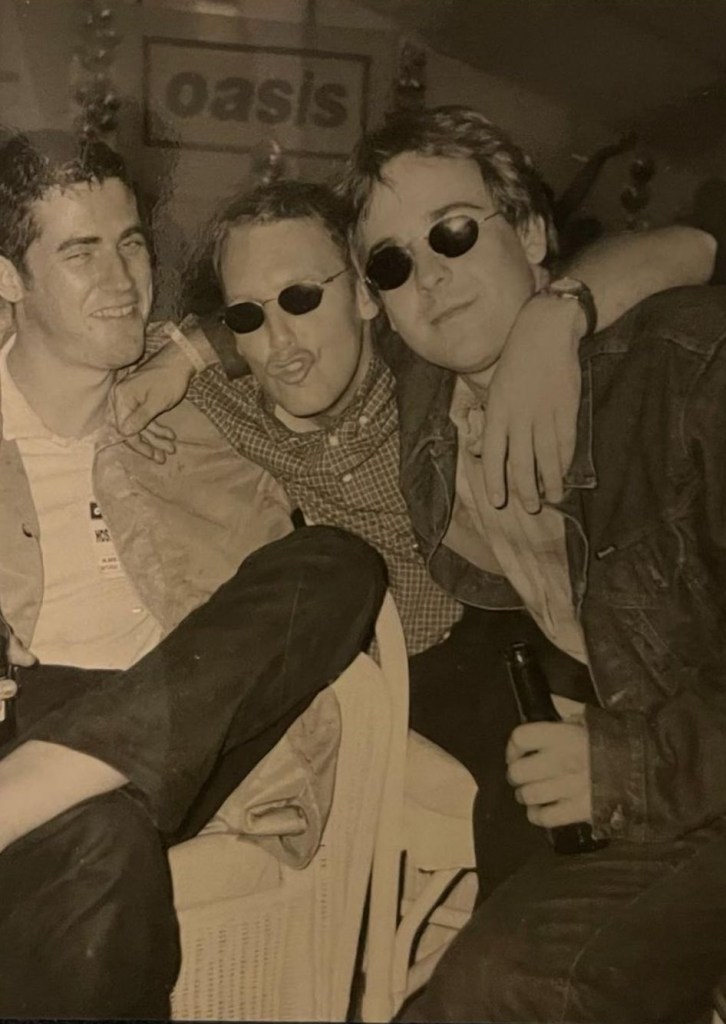

It had all happened very quickly. At the beginning of 1994, they were playing tiny venues like the Water Rats in King’s Cross or the Forum, in my hometown, Tunbridge Wells – where people who were there still brag about the fact today. Then, that spring and summer, they simply exploded. Something about their look, their sound, their imagery just seemed to fit the zeitgeist. In 1994, it was hard to avoid the conclusion that Oasis were, in the words of Manchester’s previous briefly all-conquering guitar band, the Stone Roses, what the world is waiting for.

The following year, they were in a contrived and much-hyped duel with Blur for the number one single spot. But while they may have lost that battle, they very much won the wider Britpop war. The year after, they confirmed their status as Britain’s biggest band by playing to 500,000 people over two nights at Knebworth. Oasis had attained a kind of saturation ubiquity. They were everywhere. You could hear them coming out of every passing car’s stereo, in every pub, on every football terrace. For a couple of years in the mid-1990s, apparently everyone was feeling supersonic.

After the enormous popularity of their first two albums, the moment passed almost as quickly as it had arrived. People began to realise – as I did that night at Knebworth – that they weren’t the new Beatles. They weren’t even the new Slade. They were a clunky pub tribute act who had got lucky – and that luck had reached its zenith at those Knebworth shows in 1996.

The reason I was so drunk that night was that the beer in the press tent was both free-flowing and free – and the mood was festive. But then, as the band hit the stage and we rushed out into the crowds, I immediately became separated from my drinking partners. I spent the next hour or so moving from one standing vantage point to another, trying to find a place in the crowd where the people behind me weren’t loudly but tunelessly singing along to every line as if it were a football chant. But no such place seemed to exist. Each song sounded more awful than the last. Having finally stooped over into a hedge and passed that very visceral reaction to seeing Oasis live, I staggered back to the bar, got another beer, and stood alone, missing the encores entirely. It’s something that I have never regretted.

David Hepworth, in his book Hope I Get Old Before I Die, sets out a thesis that makes the Oasis reunion seem that it was always inevitable. The music industry has shifted completely from being financially powered by CD sales at the time of Definitely Maybe and (What’s The Story) Morning Glory? Now its biggest revenue stream by a mile comes from live shows – and the flogging at these shows of ‘merch’.

But bands are brands, and solo former members almost never have the same cachet when they appear under their own names. Hepworth cites the example of how Roger Waters struggled to sell tickets to his 1990 performance in Berlin of what was essentially ‘The Wall by the man who wrote it in the place famed for it’ – when he could have sold out many times over if he’d roped in David Gilmour and performed as Pink Floyd. But the pair hated each other too much for this to be possible.

The public spat between Liam and Noel Gallagher seems to have gone on for decades, but they actually existed as a group until as late as 2009. Unlike the genuine mutual hatred of Gilmour and Waters, it always felt like the Gallagher brothers were performatively baiting each other for show, like two camp old wrestlers trying to hype a crowd, rather than because they truly disliked each other. Certainly, I’m not sure that either can dislike the other as much as I dislike both of them.

But I digress. Hepworth’s point is that the Gallaghers appearing together as brand Oasis won’t just be twice as lucrative as either appearing solo – but many, many times more so. So it was always going to happen. Because in all but the most extreme cases, money is eventually more compelling than a never-ending feud. After 15 years together followed by 15 years apart, I guess it’s time to begin the Oasis cycle again.

Looking back now, Knebworth seems to represent something of a turning point for me. For a decade leading up to it, my life had revolved around nightclubs and gigs. But a few months after Knebworth, I was no longer a lad: I turned 30, got married, and very soon had children. I became interested in cookery and gardening, birdwatching and opera. I began to drink wine rather than lager. I don’t think I ever voluntarily listened to Oasis again.

I happened to be in Manchester the night the reformed Stone Roses played their homecoming show in 2016. Our hotel was full of now middle-aged men who had dug out their old 1990s bucket hats and begun once again to walk with the strutting ape gait that characterised Manchester lad culture in the 1990s. Nothing could induce me to attempt to walk that walk again. I stumbled away from it forever 28 years ago. But I don’t look back in anger – more in mystification that I could ever, even briefly, have been a fan.

Comments