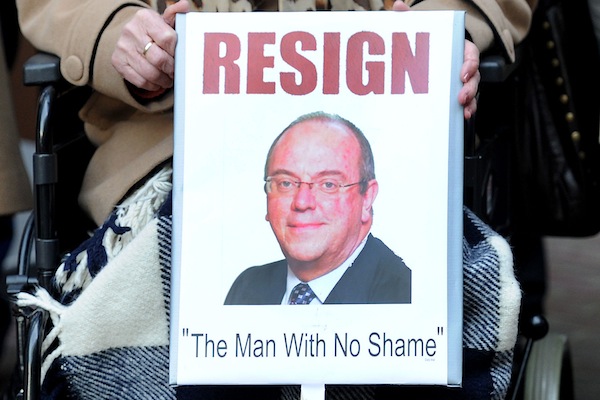

Twenty-five years ago, when he had left the Communist party and taken over as chief executive at Doncaster Royal Infirmary, Sir David Nicholson made a point of promising his staff a ‘job for life’. He has certainly stuck to his ideology. This week he admitted his part in the Mid Staffordshire hospitals scandal, in which up to 1,200 patients died from poor care and neglect. He confessed that as chief executive of the Shropshire and Staffordshire Strategic Health Authority — the body which was supposed to oversee Stafford Hospital — he had failed to notice its high death rates. And yet still he appears to believe that he has the right to stay as NHS chief executive for as long as he likes.

If Sir David’s career were one of those charts at the bottom of an NHS bed, it would now be flat-lining, with just an occasional flicker. He commands no authority and inspires no confidence. In front of the health select committee this week, he excused himself — and all other individuals — from personal blame for Mid Staffs on the grounds that the scandal coincided with a period of reorganisation. He then explained that he had to stay in his job because the NHS was again undergoing great bureaucratic change and he was needed to see it through.

The words with which he tried to excuse himself from the Mid Staffs scandal deserve closer examination: ‘For a whole variety of reasons, not because people were bad but because there were a whole set of changes going on and a whole set of things we were being held accountable for from the centre, which created an environment where the leadership of the NHS lost its focus. I put my hands up to that and I was a part of that.’ Cut through the waffle and it comes down to this: things sometimes go wrong, but individuals are never to blame, only systems and structures. It is a familiar story from past public sector scandals. The answer, we are always assured, is that ‘procedures have been tightened up’. That is the public sector all over. The test should not be whether ‘people were bad’ but whether they ought to be accountable when things go badly wrong under their watch. This basic principle is almost entirely absent from the civil service, which helps explain why so many calamitous mistakes take place. Even popes resign more readily than public sector managers.

Jeremy Hunt could have responded to the Mid Staffs crisis by trying to stamp out the complacency and the reluctance in the NHS and getting rid of underperforming staff. He could have insisted that standards should be higher in the NHS than any other part of the government machine, given that lives are at stake. But instead, both Jeremy Hunt and David Cameron have chosen to stand by Sir David, and as a result they appear as compromised as he is.

The government ought not to have been damaged by the Mid Staffs scandal, the entire duration of which fell during Labour’s time in office. Once, the Prime Minister stood for election promising to be the man who would sort out these failings. It is odd to see him stand today as a figure of the establishment, a technocratic apologist for sloppy performance and near-criminal culpability. Mr Cameron once said his principles could be summed up in three letters: NHS. If he meant it, he should dismiss Sir David forthwith.

Death of a dictator

Hugo Chávez, who died this week, was not the worst dictator in history. At times he carried off a good impersonation of a slow-learning democrat. But his instincts always remained the same: authoritarian. From first to last, his grabs at power both at home and abroad were propelled by military coup, constitution-gerrymandering and classic demagoguery.

Despite the risible claims of his apologists across the West, Chávez had all the necessary hallmarks of dictatorship. His infamously haranguing and rambling speeches were run on all channels in Venezuela. His reaction to criticism was anger. When the Catholic church in Venezuela spoke out against his authoritarianism, Chávez turned his ire on the church. The just and fair society he pretended to be creating had one of the worst crime and murder rates in the world.

Chávez referred to his politics as ‘21st-century socialism’. In the twilight years of Castro, he hoped to inherit that man’s -totemic (and pointless) anti-American mantle. It was not to be, and not just because Chávez has predeceased his friend, but because socialism continues to show itself just as incapable of bringing human happiness in the 21st century as it did in the 20th.

Comments