This week chanced to give me a fascinating study in contrasts and comparisons: Mark-Anthony Turnage’s Greek at the Linbury Studio, Britten’s Death in Venice at the Grand Theatre Leeds. Two English operas from the latter half of the 20th century, both with mythological undertones and overtones, one of them the noisy announcement of his presence by a young composer, the other the last testament, a dying fall, of the ultimate Establishment figure who contrived also to be seen as an outsider; one full of profanities and vicious humour, the other both subversive and genteel, without a trace of irony or laughter.

Death in Venice, the opera, has never much appealed to me. Though it doesn’t betray Thomas Mann’s great novella in the gross way that Visconti’s movie does, it still fails to get close to its heart, as it is almost bound to do. Tod in Venedig is written almost exclusively in the third person, mostly telling us about Aschenbach and the effects that his Venetian adventures are having on him: that allows Mann to exercise his famous irony, by no means all of it unaffectionate, to the full. Music is almost incapable of irony, and certainly it’s not Britten’s strong suit. So Aschenbach has to be presented to us directly, and, instead of us reading about him, he tells us about himself, and at immense length.

Death in Venice is as long as any of Britten’s operas, and feels longer, and the effect is to make Aschenbach seem a ponderous, self-righteous and self-tormenting windbag. Originally Britten wanted his monologuing to be spoken, but then changed it to the dryest of dry recitatives, with perfunctory piano punctuation. Needless to say, Aschenbach’s musings in the novella on Beauty, Form, the Abyss, and so forth still had to be drastically curtailed, with the result that they emerge simply as pretentious ejaculations, and with little relation to the ongoing story, while in Mann they are all part of a perfect unity.

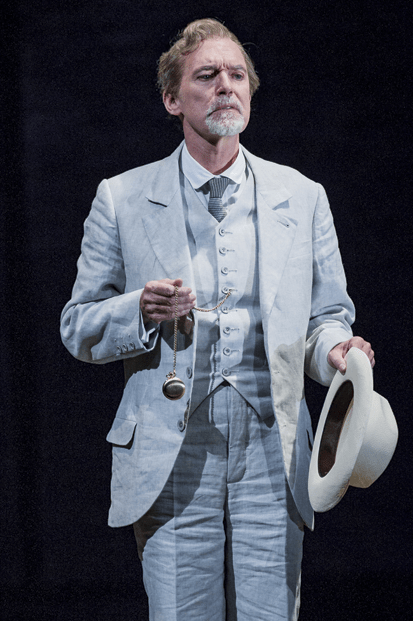

Under the circumstances, Alan Oke’s portrayal of Aschenbach is outstanding, though even he can’t rescue Act I from its stilted longueurs. Can’t anyone take the risk of alienating Aldeburgh and cut it? Act II is much stronger, once Aschenbach’s decline into rouged and pathetic pederasty gets truly under way, and Oke’s acting, as well as his tireless singing, become disturbing to a degree I would never have imagined, despite the desperate ineptness of Myfanwy Piper’s text. It would have been still more effective in a more atmospheric production.

This one by Yoshi Oida, originally seen in Snape in 2007, has dismal sets by Tom Schenk, a brown wall at the back, with a square in the centre, which changes colour in a moody way, and duckboards above a couple of pools, not visible from the stalls. Not a hint of La Serenissima in its seedy and alluring glamour. The View motif, a kitschy movie-music moment, repeated a couple of times, has no visual counterpart. So clothes and acting have to do all the visual work, and on the whole they do it very successfully, even if casting Tadzio, a silent role, as a young woman seems bizarre. What makes the home stretch of the opera successful in this account is the superb playing of Opera North’s wonderful orchestra, conducted with revelatory clarity and impact by Richard Farnes. The gamelan effects have never seemed so magical and so sickly, and as they trickle to a stop a shocked and respectful audience — to adapt Mann’s closing sentence — maintains a lengthy silence.

I wish I could have seen Greek after Death in Venice, not a couple of evenings earlier. It makes a kind of satyr-tragedy, with an East End family reliving the horrors of Sophocles’ Oedipus the King. Music Theatre Wales is touring with this production by Michael McCarthy, and, if it’s within 200 miles of where you live, go. I found it marvellously invigorating, even if Steven Berkoff’s jokes and other shock tactics haven’t always aged too well from the 1980s. Marcus Farnsworth was announced before the Linbury’s first night to be in sharp physical decline, but he was quite loud and mobile enough for me. His is a blatant and subtle account of a yob who learns the hardest way how to feel and suffer, and how, after all the eye-eliminating ketchup, to throw off the chains of tragedy and rampage out of the action, while the other characters slowly, shell-shocked, drift away.

It’s one of the few operas that I have wished to be longer, its enormous energy coming off the stage and encouraging the audience to burn a few boats. Louise Winter, who plays Doreen, the play’s Jocasta, is a fit partner for Farnsworth, and has a moving aria at the heart of the piece. There is a smallish orchestra that makes enough noise for a huge one, in a variety of styles, and though the only props are a couple of tables and a few chairs, there is no sense that anything more elaborate would better serve Turnage’s purpose. I wish there were a few more works like this around, but something of this quality discourages, I suppose, even distant successors.

Comments