In the early summer of 1910, a naval officer, bound for the Antarctic, paid a visit to the office of Thomas Marlowe, the editor of the Daily Mail. He had come in search of some badly needed funds for his expedition, but just as he was leaving he paused to ask Marlowe when he thought war with Germany would break out. ‘I can only tell you,’ came the reply, ‘that there is a well-informed belief that Germany will be ready to strike in the summer of 1914 and it is thought that she may do so.’ The officer mulled this over, doing his calculations. ‘The summer of 1914 will suit me very well,’ he said, ‘By that time I shall be entitled to command a battle cruiser of the Invincible class.’

It is ironic, as his biographer Diana Preston noted, that Captain Scott might only have survived the Pole to end his days at Jutland, but the prospect would certainly neither have disturbed nor surprised him. From the day that the Admiralty had identified Germany and not France as the likely enemy, the navy had trained for Armageddon. Newspaper editors and invasion scaremongers rattled their sabres. Socialists and syndicalists across Europe were deeply suspicious that the governing classes would play the patriot card; and what with Jacky Fisher ready to announce as early as 1911 — as if it were a wedding and not a war he was planning — the precise date, place and British ‘Admiralissimo’ for the coming Battle of Jutland, the outbreak of the Great War can seem to have been only a matter of time.

‘Very few things happen at the right time,’ however, as Herodotus said, ‘and others do not happen at all,’ and if Europe was certainly ready for it when it came — Rupert Brooke was not just speaking for himself when he wrote ‘Now, God be thanked Who has matched us with His hour’ — does any of this mean that war was inevitable? ‘1914 might be remembered for a coup in Germany,’ Jack Beatty opens The Lost History of 1914, his exuberant and bulging rag-bag of counterfactual history that challenges the ‘cult of inevitability’ that Europe’s war-leaders were retrospectively so eager to embrace:

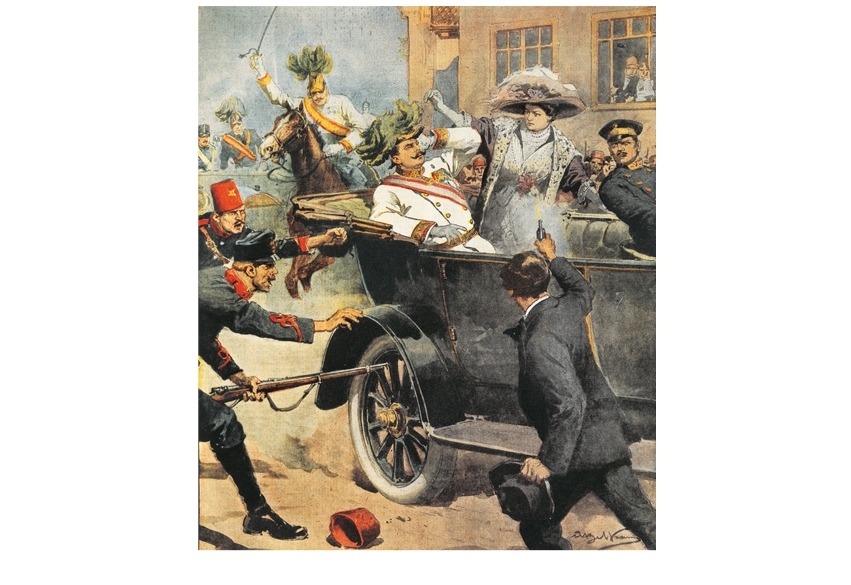

A polar shift in foreign policy in Russia, a civil war in Britain, a leftist ministry in France pursuing detente with Germany. If any of these things had happened, 1914 would not be remembered as the year World War I, as we know it, began. If Franz Ferdinand, the heir apparent to the Austrian throne, had not been murdered at Sarajevo in June, the war might not have happened at all. Most books about 1914 map the path leading to war. This one maps five paths that led away from it.

This is bold stuff, and if it never quite delivers on its promise, there is a mass of interesting and wide-ranging material on the way. The book opens with an essay on the Zabern scandal and the ghastly Lieutenant Gunther von Forstner, and lurches off across Russia, Ireland and Villa’s Mexico before doubling the Atlantic again to Sarajevo and the Paris of the Calmette murder trial in search of those forgotten, Eliotian paths that the world did not take in 1914.

There is not much in the way of logical historical argument here — why should the Curragh Mutiny have done anything but increase the chances of German aggression, for instance? — but then ‘argument’ is self-confessedly not Jack Beatty’s strong suit. In his acknowledgements he thanks everyone from his editor to his son for imposing a bit of structure on his thoughts, but if it is really true that Rachel Shteir — author of The Steal: A Cultural History of Shoplifting — ‘identified lapses of style, organisation and thinking in several chapters’ or Beatty’s son, Aaron, ‘rewrote much of the Russian chapter,’ then God only knows what the manuscript must have looked like before they got to work on it.

There is so much that is fun to read here, so much that is new, so much excitement for the subject, why could no one stop Beatty from going off like some uncontrollable Congreve rocket? In almost every chapter there is the germ of a real story, and yet time and again the narrative flow is lost, diverted into a side channel, blocked by some contradiction or irrelevancy, or simply lost in a sentence so obscure that it is hard to know whether it is careless grammar, editing, printing or just — like the faint outlines of old pathways visible in a drought — the skeleton of some earlier draft that is to blame: ‘At the Foreign Office, Grey’s aides competed in ripping the Teuton, certain he meant Grey rejected their more extreme advice, but years of it coloured his conduct of foreign policy.’

This, though, is a generous, stimulating book and Beatty’s method — or lack of it — has its compensations. Who would willingly do without the following passage, in which Edward Bennington recalls pre-war life under Hubert Gough:

It so happened that I was in command of ‘A’Squadron and brought it to parade five minutes before time. Goughy appeared at 9.00 am and had his trumpeter sound ‘Squadron Leader’. We all galloped up and saluted, and he addressed us as follows. ‘Good morning, gentlemen. I noticed 1 squadron on parade this morning five minutes early. Please remember that it is better to be late rather than early. The former shows a sense of sturdy independence and no undue respect for higher authority, the latter merely shows womanish excitement and nervousness. Go back to your squadrons.’

What a different story it might have been if Britain’s cavalry had learned the virtues of lateness a little sooner in its history.

Comments