The question of who is going to buy EMI Classics took up most of 2012 and seems destined to run well into the new year. Given that the catalogue in question is probably the most extensive ever put together, containing priceless recordings from the earliest days of so many great artists that it would be otiose even to start listing them in this confined space, you might think that here was the sale of the century let alone of the year. In fact, no one seems to want it.

The reason for putting such a property up for sale is that Universal, which already owned much of the music industry, last March began negotiations to acquire EMI as well. The European Commission ruled that for one company to own such a huge share of a market was unsatisfactory, and would only agree to the merger if Universal were to divest itself of a third of EMI’s assets. This led to a flurry of promises and evaluations, rapidly accelerating into wonderful detail.

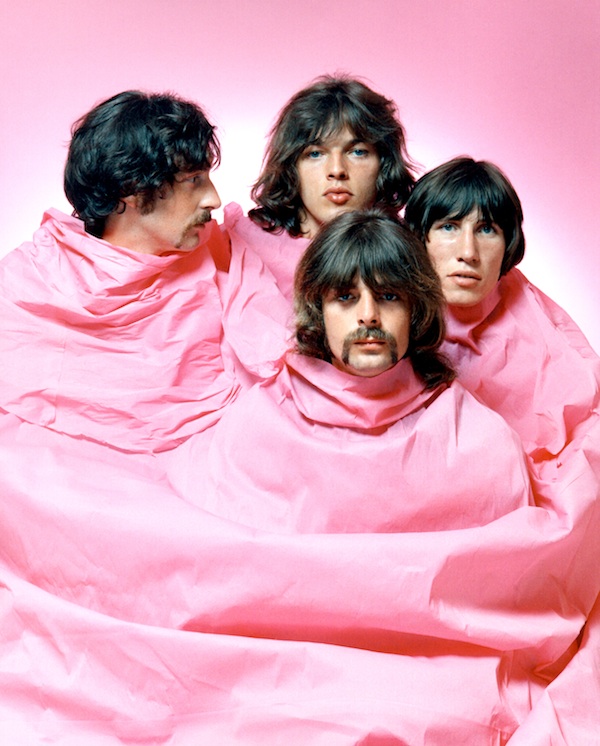

First we heard that Universal would ‘sell the Virgin Classics label in Europe and the British catalogue of Pink Floyd. A sale of Chrysalis Records would not include songs by Robbie Williams.’ This was followed by, ‘Universal has offered to sell Parlophone Records, home to Coldplay and Gorillaz, in the UK while keeping the label’s Beatles songs. The company will also sell some labels including EMI Classics and Virgin Classics in Europe.’ Finally last September Universal assured European regulators that it would dispose of assets to the tune of more than €250 million to soothe their concerns, at which the EU allowed the merger to go ahead. Richard Branson declared he would bid for Virgin Records, the music label he started in London in the 1970s.

Of course, the real thrust behind all this is who is going to own the pop labels, in particular those that are home to Coldplay, David Guetta and Pink Floyd. Despite the nostalgia behind EMI Classics, the money its discs can actually be expected to bring in has fallen to the point of being calamitous. What was already a very bad scene for classical music CDs when Universal started its campaign has become even worse in recent months, as the combination of financial crises, the closing of retail outlets and the advance of downloads has taken its toll. At this rate it will soon be hard to go out and buy a copy of a CD in a shop. Of course it remains possible to have one sent direct from online outlets, and it is always possible to download the tracks and print out the booklet, but even with this help there is no doubt that an already small market is still shrinking.

The irony is that more recordings are being made than ever before. Which behavioural law is at work to explain that one? One answer is that every ensemble and every artist, right up to the grandest and most established, are now releasing what used to be called demo tapes as full-blown commercial products, paying for them themselves. This may help them to get concerts (which was exactly the purpose of demo tapes years ago), but very few indeed are going to make money from their discs.

This makes it difficult to put a price on the EMI catalogue. On the one hand, it is priceless; on the other it is a very dodgy business proposition indeed. I believe the asking price has been $80 million, though recently an inside source told me that 30p and a sandwich would be nearer the mark. Likely buyers such as Warner, Sony and BMG Rights Management swagger about making big-time noises of interest without committing; but maybe the real answer lies in a different direction.

It has occurred to a number of us that in the uncharted waters the industry is now entering there may be hidden opportunities in this tremendous catalogue outside the obvious tried and tested ones — it’s just that exploring them is not worth $80 million. The only thing we know for sure is that in the future fewer and fewer people are going to buy CDs from shops. What they are going to do remains a mystery, since the download phenomenon has not yet come anywhere near replacing the revenue that until recently came from traditional retail. Yet throughout all the crises the public’s desire to collect recordings has never wavered: no one is saying that that desire is about to dry up. If the price were right, many entrepreneurs would surely consider acquiring EMI Classics, and hold tight until things become clearer. Meanwhile the current impasse will continue until the men in suits start thinking outside the box. The EMI catalogue is like a beautiful but useless building from the distant past, awaiting a new purpose.

Comments