‘I would lend you my copy, but the fucker who previously borrowed it still hasn’t given it back.’ Those precise words were uttered to me by an eminent churchman, more in anger than in sorrow, while chatting at high table about a book he believed I might find useful. Its title has long since slipped my mind, but I remember thinking at the time: who lends a book to a friend and seriously expects to get it back? Few things can be so often borrowed and so seldom returned.

I must confess to having felt a shudder of illicit magic when intoning the words ‘Anathema marathana’

This new and delightfully puckish collection from the publishing arm of the Bodleian Libraries, edited and introduced by the medievalist Eleanor Baker, brings together more than 70 examples of ‘book curses’, from ancient Babylon to 20th-century America, intended to deter potential thieves or forgetful borrowers. Many of their authors, appropriately enough, were members of the clergy, amplifying the stakes of earthly punishment with the prospect of divine retribution. They make my old dinner companion seem like a teddy bear.

The curses range from the venomous to the sadistic. On the one hand, there is something to be admired about the stolid minimalism of the 13th-century Suffolk monk (or possibly nun) who inscribed one library copy with the warning: ‘Whoever steals this book will be hanged by the neck.’ Almost the equivalent of stating that shoplifters will be prosecuted. Equally simple but enjoyably evocative is the ‘return me or die’ that closes another medieval curse, as though the scribe would personally track the thief down and shank him between the ribs.

At the other end of the scale are gruesome jinxes such as ‘May the devil rot off his skin’ and, in the mind-twistingly Boschian vision conjured by one German monk:

May he die a death, may he be cooked in a frying pan, may the falling sickness and fever attack him, and may he be rotated [on a wheel] and hanged. Amen.

Finishing the list with ‘and’ instead of ‘or’ rather suggests that the unfortunate miscreant will suffer all these fates in sequence – a nasty way to go. And that final ‘Amen’ is a nice touch.

There is an inevitable dip in quality as the book goes on. The threats of more recent centuries begin to sound half-hearted, and in one or two instances positively twee. ‘Those who steal this book: send them straight to the pearly gate’ hardly strikes fear to the heart, while John Clare’s contribution to the genre, ‘Steal not this book for fear of shame’, is about as insipid as you can get. One worthy exception comes from a nameless early 20th-century American thug: ‘Don’t steal this book. If you do I will beat your brains out.’ As Baker notes: ‘The reader is left to wonder if he planned on beating the thief’s brain out with his fists or with the book itself.’ Either way, top marks for effort.

Although the curses themselves are the star of the show, Baker’s editorial interventions are informative and often quietly amusing, supplying the durable thread required to link together this otherwise cacophonous compendium. With curses being drawn from sources written in Latin and Old and Middle English, translation is a necessary evil. Here and there I found myself quibbling with Baker’s choices, and her versions sometimes lack the incantatory music of the original texts. But any harm is outweighed by her laudatory decision to include transcriptions of the curses in their original languages, allowing readers to follow along and make their own choices. I must confess to having felt a shudder of illicit magic when intoning the words Anathema marathana – a common refrain in the medieval examples. One can only hope that any enchantments ceased to be active long ago.

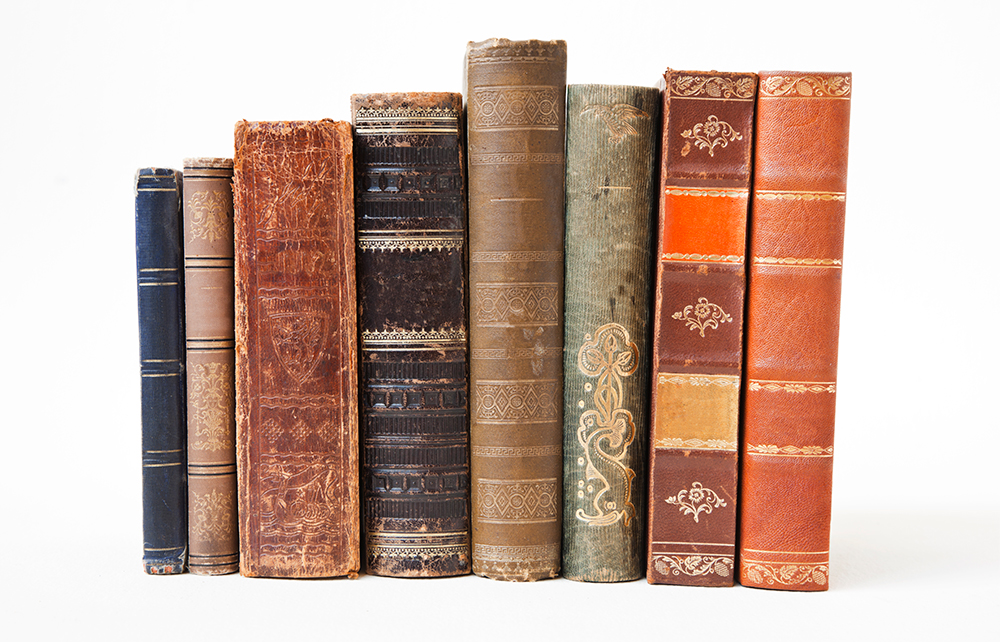

This, then, is a charmingly produced anthology that wears its learning lightly. Although there are no illustrations, the Bodleian has printed it in a pocket-sized format, handy for dipping into. It would make an excellent gift. Just don’t expect to borrow my copy.

Comments