When my husband, Robin, and I first discussed how we might try to have a child, we were against exploring surrogacy. Wasn’t this something that only celebrities did in America? Was it really in children’s best interests? How could you be sure that the women were not being forced?

Five years later, and we have a son, Solly, who has just turned three and was born through surrogacy in the UK.

There were two things that changed our minds: meeting these women and hearing them speak for themselves; and reading academic research, which is clear that children born through surrogacy are just as likely to flourish as anyone else.

Undoubtedly surrogacy can be exploitative, particularly in developing countries, with women coerced, sometimes by abusive partners, into carrying babies for rich foreigners. However, surrogacy can also be pursued ethically – when women with agency choose to carry children for others.

The egg donor chose to remain anonymous, but it’s Solly’s legal right to have her details when he’s 18

In 2018, a colleague of mine told me that he and his husband were going through surrogacy in Britain. I learned that it is legal here, but non-commercial: you cannot pay surrogates to carry your child, only cover expenses, such as maternity wear, travel expenses for appointments, loss of earnings and medication.

We listened to various podcasts in which surrogates spoke of the pride they felt in helping couples create families, and the lifelong relationships they formed with them. We wanted to find out more, so tentatively signed up to Surrogacy UK, a not-for-profit organisation that hosts events where surrogates can meet ‘intended parents’, a term in the surrogacy community for couples like us. (I use the term ‘surrogate’, rather than ‘surrogate mother’ because every surrogate I’ve met preferred this wording.)

The first surrogacy event we attended was at a pub near Stroud. We spent most of the day with a small powerhouse woman with a blonde bob and a Brummie accent who had carried twins for a gay couple. She still travelled the country for surrogacy events even though she could no longer carry. Clearly this wasn’t some kind of speed-dating style event, but a lively community.

Over the next few months we met many women who wanted to be surrogates, or who had been surrogates. They came from a variety of backgrounds. Most already had their own children. After six months, we met Rachel, a teaching assistant, and her husband James at a pub in Derbyshire and ended up spending the day together. A few months later, we returned there for another event and met her again. That time she was with her sons Charlie and Jack, then seven and five.

A few weeks later we got a call from Surrogacy UK telling us Rachel wanted to get to know us better. At Surrogacy UK, intended parents aren’t allowed to ask surrogates if they want to carry a child for them. Rightly, surrogates are in control. We spent the next few months travelling to and from Rachel’s home. She had been inspired to become a surrogate by her sister, who had carried for a couple with fertility problems.

We went through paperwork outlining different awful decisions you might have to make during a surrogate pregnancy – such as whether the surrogate would have an abortion in extreme circumstances – and were relieved that we agreed on every point.

Separately, Robin and I made embryos at a fertility clinic with an egg donor. Crucially for us, the egg donation agency didn’t have lists of donors for couples to choose from. Instead, we were interviewed, and our details sent to potential donors. Three months later we were chosen by a woman who liked the sound of us. She chose to remain anonymous, but it’s Solly’s legal right to have her details when he’s 18. We will of course support him in finding her if he wants to.

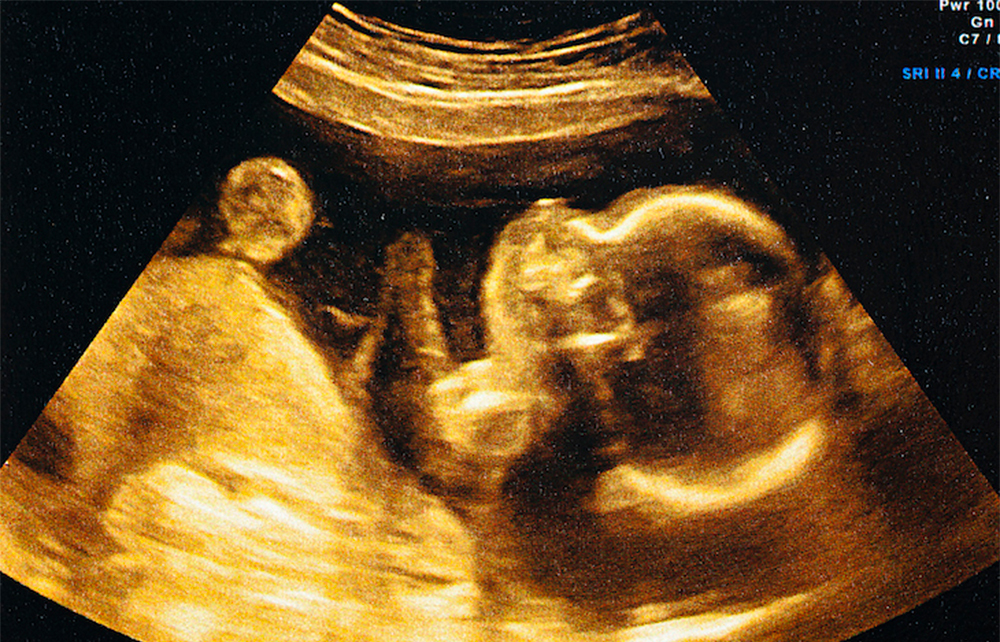

After signing an agreement with Rachel and having counselling separately and then together, our first frozen embryo – which was made with Robin’s sperm – was transferred to Rachel in July 2019.

Nine months later Solly was born. We were all together for the birth. Rachel and James cuddled him. After spending a magical hour together in the labour ward, we had two rooms: one for me, Robin and Solly, and one for Rachel. We watched Solly with the lights low, reaching out to touch his chest and check he was still breathing, again and again, like all new parents do. Rachel could come and see us as she pleased but chose to have some toast and sleep before coming back to our room to join us in the morning.

After we left the hospital, Robin and I spent the first few days in a rented cottage close to Rachel’s home. She seemed joyous after the birth and we stayed in close contact to make sure she was fine. Solly was a newborn: he just needed love and feeding. There was never any issue with bonding. Rachel expressed milk which he had at the start as well as formula.

Rachel says being pregnant with a surrogate baby was a ‘totally different’ experience to having her own. ‘I knew the child wasn’t mine. I felt connected to the baby but in a very different way,’ she wrote in my book The Equal Parent, which is about how dads should properly share responsibility for childcare. ‘It is a strange feeling, being proud of yourself… When I see photos of Solly with his dads, or videos of him laughing when he is playing with his grandparents, I think to myself: “I did that. I had a part in bringing that happiness to them.”’

We are still close to Rachel and her family, chat regularly and stay with each other a few times per year. If you ask Solly whose tummy he grew inside he says, ‘Aunty Rachel!’ His middle name is Ezra, which is Hebrew for ‘help’, to honour Rachel.

No matter how often Rachel and other British surrogates speak about their reasons for helping people become parents, they are often viewed with suspicion and told they cannot possibly know their own minds. This doesn’t tally with our experience with Rachel and all the other surrogates we’ve met. At their most damning, critics who claim to care for these people’s welfare insult them and compare them to breeding animals. It is deeply hurtful. Since Robin and I started posting about our family online, we have been accused of ‘erasing motherhood’, denying Solly his heritage and treating him like a commodity.

At the moment, you can go through surrogacy in the UK independently, without oversight

Of course women carry and give birth to babies. There’s no suggestion mothers aren’t central to most families. But if some women want to altruistically donate eggs and carry children for non-traditional families, what’s most important for kids is having positive relationships with their parents, regardless of their genetic make-up. Last month, a major review of worldwide academic studies in this area published in the BMJ Global Health journal found children with same-sex parents fare just as well as, and sometimes better, than those from ‘traditional’ families.

Academic work has also suggested it is vital these children are not misled about their origins. We are following this advice.

About 450 babies per year who are brought up in England and Wales are born through surrogacy. Critics often point to a few horrific cases from foreign countries, and they should absolutely be studied carefully. But these are not representative of surrogacy here. However, while we found a way to have a child that we felt was ethical, the law has not been robust enough to ensure this in all cases. That’s why the Law Commission’s proposed changes have been widely welcomed, including by UK surrogates.

At the moment, you can go through surrogacy in the UK independently, without the oversight of an organisation like Surrogacy UK. There is no regulator. We chose to go through pre-conception checks – such as counselling and discussing the medical implications with Rachel – but this was our preference; it wasn’t legally required.

Initially, Rachel and James were listed as legal parents on Solly’s birth certificate, even though they didn’t want this status. We went through a six-month ‘parental order’ process in the courts for them to pass on these theoretical rights to us.

In practice, it didn’t affect us. But in theory, had Solly had a medical emergency, his care could have been delayed by a doctor wanting permission from Rachel and James to give life-saving treatment. Currently surrogates are at risk of being left with legal parental responsibility for a child not in their care. The proposed guidelines would allow legal parenthood to be granted at birth if the surrogate agrees – but only if a licensed fertility clinic or surrogacy organisation is used, if everyone involved in the process has had counselling and received legal advice, and if criminal record checks have been conducted before conception. The proposed guidelines would uphold the surrogate’s right to change her mind about granting immediate legal parenthood for up to six weeks after the birth. They also maintain the principle of altruistic surrogacy in the UK, with only legitimate expenses allowed.

There would be a national register of surrogacy arrangements, to ensure that anyone born through surrogacy has access as an adult to an impartial legal record of how they were conceived and born. The changes would apply only to those going through surrogacy in the UK. If people went abroad for it, they would subsequently have to go through the full parental order court process involving social services.

Crucially, surrogates in the UK, including Rachel, are delighted about the changes. We should listen to them.