The British Medical Association (BMA) has this week announced a new four-day strike for junior doctors, which will take place after the Easter bank holiday. The strike will lead to the NHS having a reduced service for ten days in a row, when you include the two bank holidays and weekends. I am a junior doctor, and have not and will not be striking.

Before explaining why, it is worth making clear who will be on strike this Easter. The term junior doctor encompasses the majority of doctors under consultant level, which for most doctors lasts around five to ten years after graduation.

My colleagues have bought nice houses, have children in private school, and the amount of Teslas in the hospital car park does not scream low wages

A doctor starts as a foundation trainee year one, or FY1, in the first year after graduation. Though FY1s have graduated medical school, they are not fully registered until the end of their first year, and there are limits on what they can do during this period. Doctors will subsequently complete a second general year (FY2) and can then apply to specialist training. For an FY1 the base rate salary is £29,384.

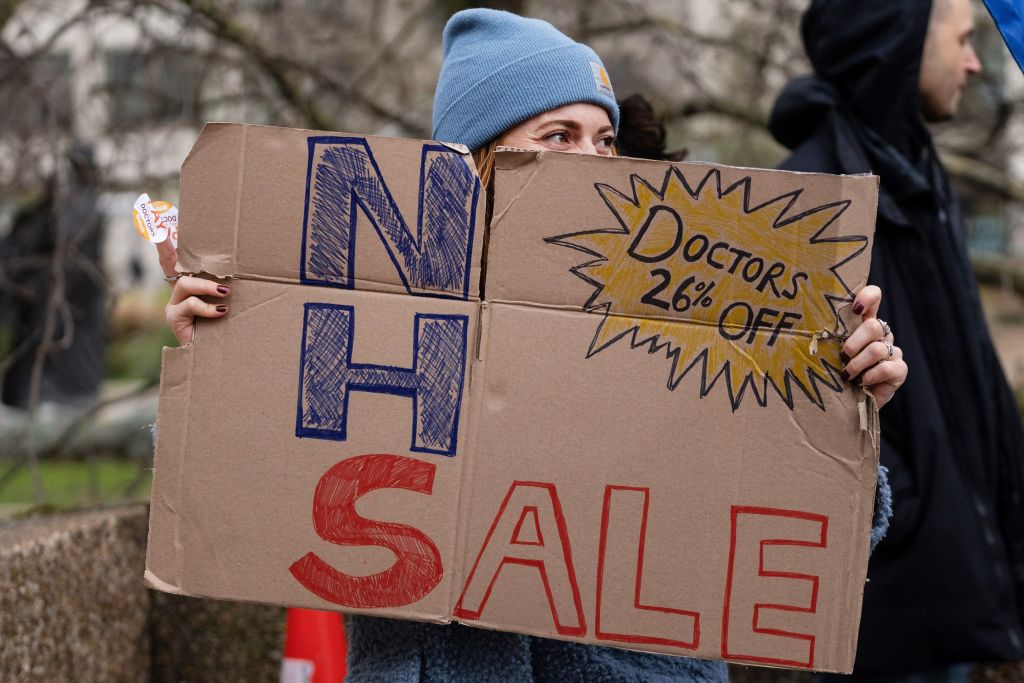

During the strikes, the BMA has used this figure – and some certified creative accounting – to suggest that this means junior doctors are only paid £14.09 per hour. It’s a catchy figure for the placards and allows the union to say that junior doctors could ‘make more serving coffee than saving patients.’

In reality though this only applies to a doctor’s first year – and pay rises quickly with experience. By the fifth year of training a doctor’s standard base salary has increased to over £51,000. This places junior doctors amongst the top 15 per cent of earners in the UK within five years of graduation. Further, these salary numbers ignore that when doctors work antisocial hours (such as evenings, nights and weekends) they get paid significantly more.

The narrative of the BMA is that this strike is about hard-working, noble, underpaid and underappreciated doctors fighting against an uncaring government. They are right about one thing: the job is hard. Junior doctors make life and death decisions every day, which comes with significant emotional strain. But hasn’t this always been the case? Physician is one of the oldest jobs in existence – even the oldest profession in the world needed treatment for venereal diseases. Every doctor working now knew what they were getting in to when they signed up. And they benefit from having a varied, intellectually stimulating job with enviable career progression and scope to move into various avenues of interest. The hours are better than they were a generation ago, with more protections against unsafe hours and limits on weekends worked.

Like all of the public sector there has been a real term pay cut for junior doctors over the past ten years or so. However, the wage is still good in comparison to other public sector workers. I earned more three years out of university then my civil servant parents retired on, both with 30 years of full-time experience. My colleagues have bought nice houses, have children in private school, and the amount of Teslas in the hospital car park does not scream low wages. For a nurse to be paid the same as a doctor three to four years out of medical school they would need to be a matron, accountable for large areas of the hospital with a significant managerial role. The pay for doctors is less in real terms then it was, but do not let the BMA hyperbole fool you: it is still appropriate for the hard work and training required for the role of medical doctor.

The strikes have been coordinated by the BMA junior doctor’s council. Last year – in a move straight from the Jeremy Corbyn momentum playbook – this council was taken over by a left-wing group called Doctors Vote. Formed on an anonymous Reddit forum of disgruntled keyboard warriors, they seem to be unswerving in their belief that junior doctors are special and deserving of adulation wherever they go. The JuniorDoctorsUk forum, where the Doctors Vote movement first originated, shows their religious zeal for the strikes, and a hatred of the non-believers. According to research from Policy Exchange, Doctors Vote and other hard-left figures, taking advantage of the low turnout in BMA elections, now make up 59 of the union’s 60 regional junior doctor representatives and 26 of the 55 voting members of the BMA Council, its national executive committee. BMA policy is now dictated by this group, which explains why it now sounds so like an over-eager student union when it comes to the strikes.

The question the BMA and its most hard-line followers don’t like to answer is where the money for a salary increase is actually going to come from. Increasing spending in a period of high inflation has historically been a bad idea, and there are lots of areas in the public sector that need investment to deliver even their basic functions. That means the money from any salary increase will have to come from the existing NHS budget.

The NHS currently has a huge backlog, with patients piling up in the emergency department. The pressure this places on doctors, and the emotional effect of operating under this stress, is significant. The problem is the number of beds and flow through the hospital. And what will fix this is more community rehabilitation facilities and home carers so that patients can be safely discharged. The cost of the first strike has been estimated to be up to £90 million, with the next strike costing more. The price of the 35 per cent pay rise asked for by the BMA would be a lot higher than this. How many community facilities could be built for this? How many more carers could we employ if we used this money to raise their wages, and improved their working conditions and progression?

People are dying daily in emergency departments up and down the country. There are much better uses of a limited healthcare budget then a pay rise for already well-remunerated doctors.

Comments