The thing to remember about Chet Baker, an old acquaintance says of the errant jazz musician in Deep In A Dream, James Gavin’s exemplary 2002 biography of Baker, is that ‘he can hurt people even after he’s dead’.

Baker could be dangerous but mostly he hurt himself. He died, squalidly, in 1988, and his music, at least, can still wound. In Baker’s oeuvre the ballads are deep blue and the up-tempo tunes are somehow tinted even darker.

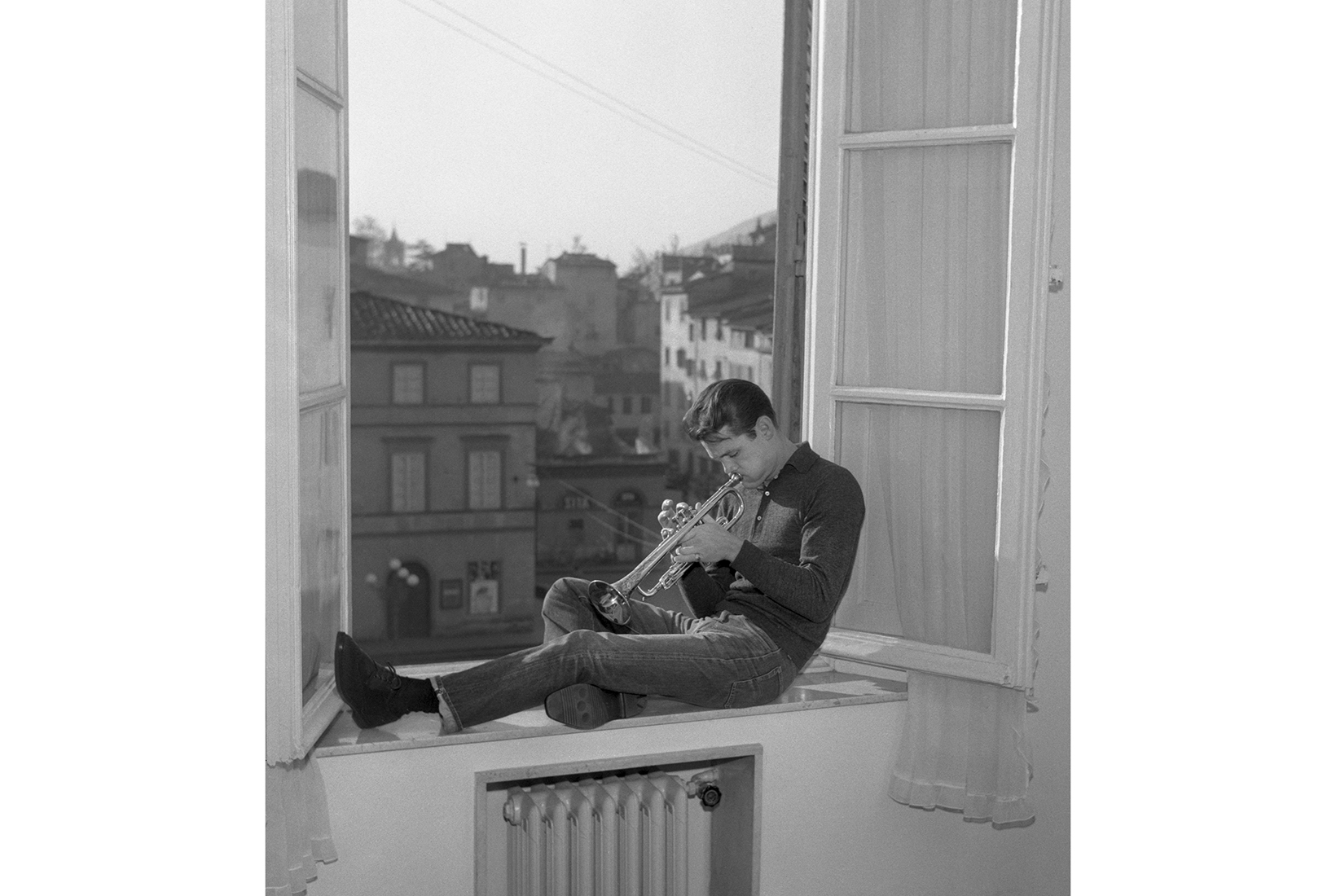

The ‘jazz James Dean’, the ‘Prince of Cool’, Baker was extremely pretty in his younger days and made music that cast a similar enchantment. His trumpet style was lyrical, his singing voice light and seductive. He was also violent, disreputable and dishonest, a heroin addict for half his life and a bit of a bastard for most of it. It’s all there in his playing. Beneath the surface pep and languid glamour, not only Baker’s smoothed-out public persona but post-war America’s impossibly romanticised image of itself can be heard curdling.

A queasy air of doomed idealism and sublimated thuggery envelops even his most beautiful music

An unschooled Oklahoma boy who learned his trade in army bands, Baker made his way after moving to Los Angeles, serving an apprenticeship in the early 1950s with Charlie Parker and Gerry Mulligan. Aided by myth-minting portraits by photographer William Claxton, a few forgettable movies and his landmark 1954 album Chet Baker Sings, Baker was briefly a pin up, but something always seemed a little off. It would be fanciful to claim to be able to hear premonitions of his unceremonious end in his signature takes on ‘My Funny Valentine’ and ‘But Not For Me’, but a queasy air of doomed idealism and sublimated thuggery envelops even his most beautiful music.

Listen closely and its effortless lyricism seems not so effortless after all. Baker sings and plays like a stone skipping over water, fearful of the depths below. The sentimentality is served junkie-style: ingratiating, obvious, nakedly tugging at the heartstrings. The results are a kind of parody of light-heartedness, counterweighted with existential dread. Baker proved the perfect jazzer for the method acting era.

Reissues of four excellent albums from his brief spell recording for Riverside in the late 1950s are instructive. Coming after Baker’s classic spell at Pacific Records, they showcase the two sides of his musical personality. It Could Happen to You foregrounds his talent as a vocalist, scatting standards from the American songbook with the naturalistic charm of a young Brando. In New York and Chet are more serious interrogations of his gifts as an instrumentalist. The former proves that, though Baker was the doyen of cool jazz, he could handle hard bop when roused. The latter, which features Bill Evans and Kenny Burrell, is laid back, expansive and perhaps his purest modern jazz recording. It gives free rein to Baker’s wistful vulnerability, his trumpet playing spare, vibrant and impressionistic.

On his final album for Riverside, Chet Baker Plays the Best of Lerner and Loewe, he barely breaks sweat covering material from My Fair Lady, Gigi and Brigadoon. In some ways this was as good as it got. After Baker left the label in 1959 he didn’t record another studio album for five years. He had started taking heroin earlier in the decade, and by the end of the 1950s it had its claws in him. The 1960s were a mess. Baker was arrested and imprisoned in Italy, then beaten up in Sausalito in 1968 while trying to score. He broke a tooth, damaging his embouchure and setting an already faltering career back several years.

By the time he re-emerged in New York in the 1970s Baker was a relic of another age. One of the great jazz musicians of the 20th century was perhaps also one of the least curious. He loathed free jazz. Fusion didn’t interest him. Primarily captivated by melody and beauty, he stuck largely to a repertoire of standards.

The latter years were spent mostly in Europe, playing for ready cash. Bruce Weber’s stark documentary of Baker’s haunted life, Let’s Get Lost, laid bare the decline. Once he had looked like a handsome sailor on shore leave. Now, cheeks sunken, eyes glazed, thinning hair slicked back, he approximated a walk-on deadbeat from Breaking Bad. Yet the music could still sparkle. His spiralling trumpet solo on Elvis Costello’s ‘Shipbuilding’, as well as Live In Tokyo, a fine concert recording from 1987, showed Baker was still capable of stellar performances.

He died in the early hours of 13 May 1988, aged 58, after falling from the second floor of an Amsterdam hotel, cocaine and heroin in his bloodstream. Given the way he lived his life, conspiracy theories inevitably clustered around his death, but it’s likely he was trying to enter his locked hotel room via the balcony next door. In a sense, the details are secondary. Whatever had been so audibly fracturing inside Baker for 35 years had finally broken.

Chet Baker’s Riverside catalogue, reissued by Craft Recordings, is available on vinyl and across digital platforms.

Comments