What is the point of UN Special Rapporteurs? On Tuesday, their expert on terrorism and human rights, Fionnuala Ni Aolain, released a report which was seized upon by the Independent and the usual dodgy ‘advocacy’ groups that speak on behalf of convicted extremist as being evidence that our counter-terrorism Prevent strategy violates international law.

Rapporteurs are independent subject experts hired by the UN and given a mandate by its Human Rights Council to investigate and report on areas of concern. I have fond memories, while at the Equality and Human Rights Commission, of being lectured on our dire housing situation by one such visiting rapporteur, the Brazilian former Marxist Raquel Rolnik (Favellas anyone?). After that visit the UK’s then-ambassador to the UN in Geneva, Karen Pierce deployed all the diplomatic firepower she could muster to say, ‘’The reaction here from UN agency heads and otjers [sic] has been who is that strange woman; why is she talking about bedrooms and why on earth do we have a UN Housing Rapporteur.’

I’ve met Professor Ni Aolain once before and she’s clearly not in the same ballpark as Ms Rolnik. She’s a hugely well qualified academic lawyer. Her 19 page report, not written in the most accessible language, critiques the operation of counter-terrorism prevention strategies across all 198 countries in the UN. She makes specific reference to the United Kingdom in her report only once and then as a beacon of good practice in terms of its integration of human rights in our counter-terror strategy.

She makes a number of important points that are uncontroversial. Weak and fragile states – and I would argue institutions – create vacuums that violent extremists can exploit. The importance of building resilience in communities to resist being drawn into terrorism is unassailable. Security responses alone won’t work. All articles of faith for mainstream practitioners in the world of counter-extremism.

But 19 pages covering global counter-extremism practice in countries with profoundly different human rights records is a huge ask and the necessity to generalise has compromised this analysis. The Independent’s headline in search of a story illustrates the point.

‘UK counter-extremism programme violates human rights, UN expert says.’

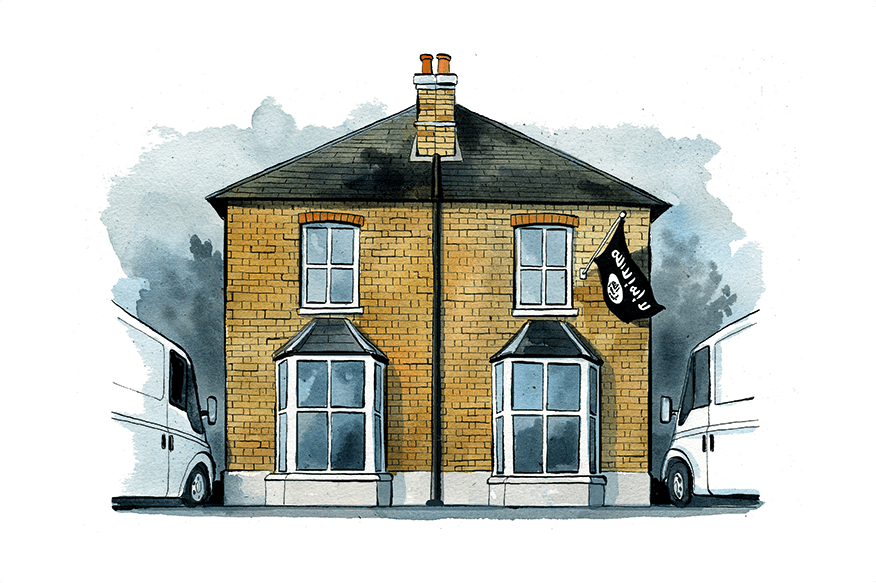

At no time does Professor Ni Aolain say any such thing. She does signal ‘profound concern’ about action in the ‘pre-terrorist’ space where the Prevent strand of our counter-terror strategy sits. This seems to relate mainly to the danger of countries with very poor human rights regimes taking advantage of a terrorist threat to shut down and silence legitimate forms of protest. While undoubtedly true in places like China and Russia that sort of concern just doesn’t fly in a country like the UK where the convention on human rights is written into domestic law and policed by an independent judiciary and a free press.

Moreover, her concern about preventative strategies that seek to harness state agencies as partners in detecting and treating violent extremism fundamentally misunderstands the UK approach. Prevent is firstly a safeguarding strategy where people identified by a range of professionals as at risk of being drawn into violent extremism are offered help and support to counter harmful views and behaviours.

Despite the relentless efforts of groups such as CAGE and MEND to demonise Prevent as Islamophobic and its practitioners as state-sponsored spies, Prevent continues to be a success story with hundreds of young people across the ideological spectrum identified and diverted from a path leading to terrorist violence. Indeed, the Crest think tank published research just last week that showed unequivocally that the British Muslim community supported the principles of Prevent and their institutions in combating Islamist extremism.

The report highlights other valid concerns about the effectiveness of current screening techniques for violent extremists, state over-reach and the lack of ‘scientific’ validation for many deradicalisation programmes. But much of what is said seems to argue for the state to roll back in its attempts to keep citizens safe or wait for certainty in a conflict with terrorism that poses spontaneous, immediate and ever-evolving lethality.

There is almost nothing in Professor Ni Aolain’s long lament that seems to acknowledge the human rights of the victims of terrorists only in the sense that she sees much of the current prevention approach as at best neutral and at worst weaponising alienated subjects of its purview. While this might play well in the corridors of Geneva it is unlikely to cut much ice at the Home Office where, at long last, the protection of the public has risen above other bureaucratic abstractions.

Fionnuala Ni Aolain doesn’t write UK newspaper headlines but her power and influence at the UN matters. Holding states to account for their legal and proportionate response to terrorism is necessary and useful. But it is also possible to go so far in the defence of conceptual ‘human rights’ that we can perversely risk the freedoms that such rights are intended to protect.

Our own UK Prevent strategy is a hugely effective exercise in safeguarding people who are vulnerable. People who might be dragged into the world of violent extremism. It does need scrutiny and it can be improved. It hasn’t always been adequately defended or explained by government, but it is undoubtedly making a difference on the ground. That’s one of the main reasons it gets attacked.

Ian Acheson is a senior advisor to the Counter Extremism Project

Comments