George Bernard Shaw argued passionately that Britain should create a public health service. And he lived long enough (1856–1950) to become one of its earliest victims. This play from 1906 shows the very best and the very worst of his creative abilities. He had a plan: to strip bare the iniquities of private medicine and stick the knife in deep. We open in Harley Street where a gang of slick and prosperous doctors are bantering away, like tipsy clubmen, about their patients. I cured this one. I killed that one. Each quack has his preferred treatment. One thinks all disease is caused by blood poisoning. Another that surgery cures every ailment. A third that cheerful nurses and a decorative sick-bay are an infallible panacea. We sit back, for an enjoyable hour or so, as these deceitful charmers engage in eloquent and revealing chit-chat. Then Shaw suddenly remembers he’s got a play to write. So he whips up a plot. One of the medics, Sir Colenso Ridgeon, has discovered a costly new cure for TB but he can spare only one extra place in his private ward. Two consumptives present themselves: a do-gooding twerp who caught the lurgy while helping urchins in the slums; and a young artist of genius who is also an incorrigible swindler.

To complete the dilemma, Sir Colenso hatches an evil scheme to seduce the genius’s beautiful wife if her husband’s treatment fails. The manipulative romance between doctor and wife fails to catch fire properly, nor does it provide the drama with the amorous twists and surprises it ought to. So why is it there at all? The answer illuminates Shaw’s besetting problem. His commercial sense obliged him to include a love affair. And his romantic sense compelled him to bungle it.

He’s more interested in demolishing the hypocrisy of moralising bourgeois prigs. And in the dazzling second act, using the artist as his mouthpiece, he pulls apart the prattling doctors and rips up their ethical codebook. It’s a brilliantly entertaining piece of rhetorical footwork. And it’s followed, rather strangely, by a Gothic death-scene that tries to be funny and deeply moving at the same time. Alas, Shaw can’t manage profundity or extremes of emotion. He can talk about them perfectly well. (He can talk about anything, and keep talking about it till the cows come home and go back out to pasture.) And he duly talk-talk-talks his way through the tragedy and bangs into the buffers. The final scene is even wordier as he creates a great escarpment of chatty moralising with no dramatic purpose whatever.

Still, there’s plenty to enjoy here. Finely tuned performances capture the period atmosphere perfectly. And the costumes and sets are exquisitely stylish. Mind you, it’s rare to find a Shaw production whose visual identity is anything less than superb. The natural elegance of the Edwardians must get some of the credit. And Shaw’s plays, thank God, carry a natural immunity to attack by conceptual design-vandals.

Aden Gillett, as Sir Colenso, has tremendous authority and swagger on stage. There’s a touch of Liam Neeson about him, too, a hint of menace beneath that smooth and tremulous surface, like a river with dangerous hidden currents. We should see more of Gillett. And in meatier roles.

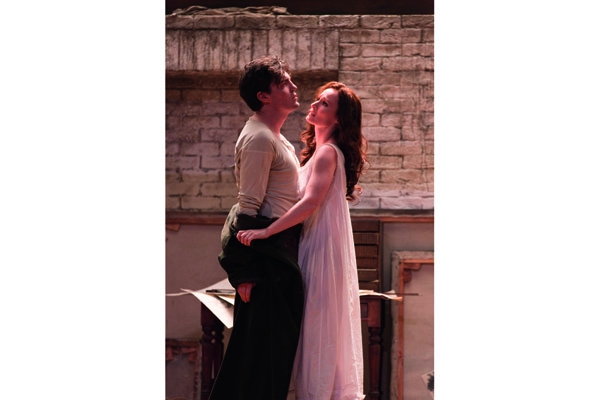

Tom Burke (as the artist) has long been playing the lead in Coward and Strindberg. He risks becoming pigeonholed as a louche Bohemian gadabout who can’t manage anything later than 1939. Perhaps that doesn’t matter. If you want a floppy fringe to mooch around a Chelsea studio wearing a vest and a pair of Oxford bags held up with a public-school tie then Burke’s your best choice.

Genevieve O’Reilly, a gifted and gorgeous actress, has landed a rare dud in the role of Jennifer. Shaw draws her as a simpering ignoramus besotted with a sponging cad. She may be the sexiest doormat you’ll ever see but she’s wasted on this nicely frocked also-ran. There’s fine work from Maggie McCarthy as a sardonic and knowing maid.

So why dredge up this venerable Shavian battle-cruiser right now? Some say it illuminates the world of private medicine at a moment when the NHS is ‘being dismantled’ and even ‘sold off’. Baffling logic. If the NHS is for sale, who is the buyer, where are the shareholders and which CEO has the unhappy task of overseeing a transaction that would trigger a national revolt? Perhaps the NT wants to show us that private medicine is corrupt, avaricious, self-serving and wholly in thrall to scientific fashion. But so is its publicly funded replica. In any case, the way to purify the profession isn’t to nationalise it but to strike off every medic who isn’t also a saint. Having done that, for want of doctors, we’d all die.

Comments