James Harrison, who died in his sleep at a care home in Australia last month at the age of 88, possibly did more good and saved more lives, pound for pound, than almost anyone else born in the last century.

His blood plasma contained a rare antibody, Rho(D) immune globulin (called Anti-D), which can be used to prevent the blood of some pregnant women from doing damage to their unborn babies. But that is under-selling it. Anti-D is extremely rare (fewer than 200 people produce enough of it to donate their plasma in Australia) and the conditions which it helps with are common.

Anti-D injections protect unborn babies from Rh disease, otherwise known as rhesus disease, and haemolytic disease, which affects unborn babies and newborns. In pregnancy, the mother’s red blood cells can be incompatible with the blood of their child. If this happens, the mother’s immune system fights the baby’s blood as though it were a virus or bacteria, attacking the cells of the child. Babies who are affected can end up with anaemia, heart failure, and they can die.

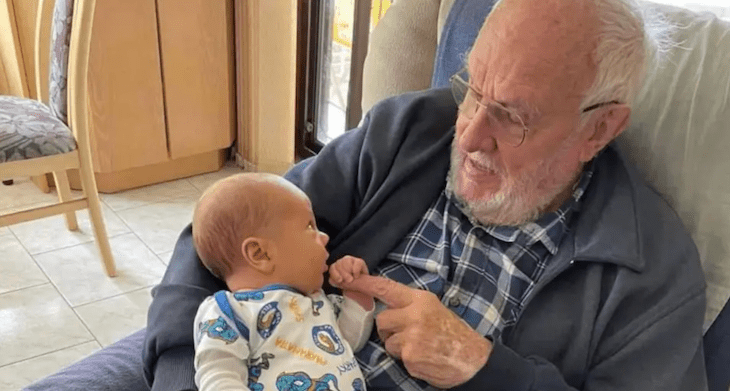

Without the immunisations, roughly half of the babies affected by haemolytic disease would go on to die. With injections provided by people like Harrison, the fatality rate and rate of serious injury drops precipitously. Millions of babies who would have been injured by their mother’s blood can be saved. By donating blood, Harrison saved babies’ lives. He saved millions of babies’ lives: up to two million, it is estimated, across Australia.

Anti-D cannot, so far, be manufactured synthetically. It cannot exist without blood donations. Donors like Harrison are necessary. For many of them, when they are tested and realise they are so vital and their capacity to help so rare, blood donation becomes a moral obligation. Harrison started donating his blood plasma when he was 18 and continued making donations every two weeks until he was 81, at which point – despite Harrison’s stated desire to continue – it was discontinued on medical grounds.

He said that as a boy of 14, Harrison himself received a large blood transfusion in the course of major chest surgery. Someone who had benefitted from blood donation ought to give himself. And then Harrison realised he was blessed, that he had the ability to do far more than ordinary donors. After which, he simply had to continue for as long as he was allowed. It was on May 11, 2018, that he made his 1,173rd – and final – donation of plasma.

In Australia, Harrison was affectionately nicknamed the man with the golden arm. He was a local and national hero, an ordinary man who was capable of helping others in a remarkable way: someone who, once he realised he could help, did so diligently and regularly for as long as his strength allowed him.

Towards the end of his life, Harrison’s blood donations began to attract more publicity. He was given a Medal of the Order of Australia in 1999. He was followed and filmed by more cameras. More and more, as time went on Harrison was asked when he would give it up, and whether there would ever be a replacement for him and his antibodies. He said that he would donate for as long as he was allowed. And he hoped that when he was unable to continue, and when he was gone, there would be new ways found to produce the antibodies.

When they were interviewed by the New York Times in 2018, as Harrison approached the end of his donations, the scientists working on synthetic antibodies said what they hoped to make was a process to produce ‘James in a Jar’.

In his lifetime, the Australian Red Cross said, Harrison had produced tens of thousands of doses worth of antibodies. Every batch of anti-D produced in New South Wales, where Harrison lived, had some of the antibodies derived from his plasma. Harrison’s was a good life, now at its end.

Comments