Either Lucy Worsley or, more probably, her publisher has given her book the subtitle ‘The Secret History of Kensington Palace.’ This is enticing, or intended to be so; it is also misleading.

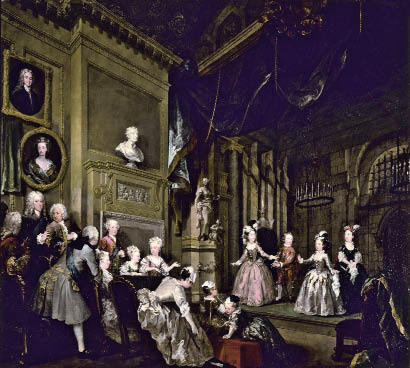

Either Lucy Worsley or, more probably, her publisher has given her book the subtitle ‘The Secret History of Kensington Palace.’ This is enticing, or intended to be so; it is also misleading. There is no secret history, and the subject of this well researched and entertaining book is life at the court of the first two Georges, life which went on also at St James’s Palace and indeed Leicester House, where George II lived as Prince of Wales, as did his son Frederick later. Indeed the book begins with a lively account of a reception at St James’s, where, ‘beneath their powder and perfume, the courtiers stank of sweat, insecurity and glittering ambition’. (What is the stench of glittering ambition?) Kensington Palace was where the court removed to for the summer months when London was even less healthy than in winter.

Neither George I nor George II is among the best remembered of British monarchs. Some may recall that the father hated his son, which became a Hanoverian habit; others that the first George was believed, probably with reason, to have organised the murder of his wife’s lover, and that the second George died on the privy. George II is, however, notable as the last reigning British monarch to have commanded his army in battle, which he did successfully at Dettingen in 1743, and for having replied to his dying, much-loved and ill-treated wife Caroline when she urged him to marry again, ‘Non, j’aurai des maitresses’, a promise which he kept. But that’s about it. They lack glamour.

George I was 54 when he became king in 1714. His hereditary claim was slight, but he was the senior Protestant descendant of James VI & I, therefore appointed successor to Queen Anne by the English Parliament’s Act of Settlement of 1701, a decision endorsed in the Treaty of Union between England and Scotland which created the Parliament of Great Britain. He was a German prince — Elector of Hanover — who spoke only broken English and had never previously set foot in his new kingdom. He neither liked not trusted his new subjects, known throughout Europe for their disreputable habit of getting rid of monarchs who didn’t suit. His new subjects didn’t care much for him either; the Scots Jacobites among them called him ‘a wee bit German lairdie’ and English Tory squires muttered about ‘Hanoverian rats’. He had no queen to bring with him to enliven the court, his wife having been shut up a prisoner in a German castle since the discovery of her adultery, but instead he brought two mistresses, one monstrously fat, the other thin and scrawny. His irreverent subjects dubbed them ‘the Elephant and the Maypole’. There were also two devoted Turkish servants who, on account of their Muslim origin, were believed to be kept for the purpose of sodomy. Lucy Worsley makes it clear that this nasty gossip was unfounded.

Indeed, she paints an affectionate portrait of George I, a shy man who shunned ceremony and did his duty conscientiously, despite his understandable dislike of English politicians and his distrust of the odd British constitution which denied the monarch the power more well-ordered countries granted him. He much preferred Hanover, and can scarcely be blamed for doing so.

His much-loathed son, George II, agreed with his father in that respect, but, like him, did the job he had been hired to perform. He had the advantage of a clever wife, Caroline, whose huge bosom was much admired. She found him boring and demanding, but they were bound together, as the great historian of Georgian England, Sir John Plumb, happily observed, by a healthy animal passion. George had a mistress, because kings were supposed to have one (or more); his long-serving one, Henrietta Howard, was an intelligent woman (friend of Swift and Pope), rescued by the king from her brutal alcoholic husband, but nevertheless bored stiff by him. His favourite pastime was cutting out paper figures. George had a fierce temper, which flared up quickly; he was also a petty bully and a nag. Actually he was insecure, and, as Plumb again observed, could himself always be bullied. He was a weak man and knew it, something very irritating for a king to realise. On the credit side, he loved music and was a patron of Handel.

We are fortunate — though perhaps George was not — in having a marvellous record of life at his court; the Memoirs of Lord Hervey are incomparably the best and most entertaining court memoirs in the English language, indeed among such things second only to Saint-Simon’s Memoirs of Louis XIV and the Regency.Hervey, mercilessly satirised by Pope as ‘Sporus’ — ‘this painted child of dirt that stings and stings’ — was a highly intelligent and observant writer who adored the Queen and despised the King. He was married to a charming and beautiful girl, with whom he had eight children, but his deepest passions were for members of his own sex — especially Stephen Fox, his beloved companion on a tour of Italy. Worsley thinks he also had an affair with Frederick, Prince of Wales, which turned sour and accounts for the vicious portrait of ‘Poor Fred’ in the memoirs. But he may have done no more than share the hatred George and Caroline had for the son they described as a ‘monster and wretch’. (Actually he seems to have been much the nicest member of the fairly appalling family.)

Worsley is excellent in her descriptions of court life and the tedium endured by those whom ambition subjected to it. She has a keen eye for oddity, offering nice character sketches. She is very agreeably informative about the lives of below-stairs servants, as well as ladies-in-waiting and equerries and other officials. She introduces oddities like Peter the Wild Boy, a mute child found living in a German forest and presented to the king as a curiosity. Swift’s friend, Dr Arbuthnott, tried to teach him to speak, with only limited success.

As Chief Curator of Historic Royal Palaces, she is, not surprisingly, very good on building work and decoration, and anyone is likely to learn a lot from this book. She doesn’t forget, either, that the king was still head of the government in reality as well as name, and that not even the most powerful politician, notably Sir Robert Walpole, could hope to survive in office without royal favour. Nevertheless, power was passing, if slowly and imperceptibly to many, from Court to Parliament. The day was approaching when Lord North would tell his master, George III, that ultimately the opinions of the House of Commons must prevail.

Meanwhile this is an engaging, splendidly readable account of the first two Georgian courts. It is lightly written, but full of information. I enjoyed it, and hope that Lucy Worsley will take the story further. The life of George IV at Windsor and the Pavilion in Brighton is surely a subject that might attract her.

Comments