In the side chapel of the church of St Giles’, at the northern apex of the historic Oxford thoroughfare, hangs a remarkable painting. ‘Menorah’ (1993) depicts the (now demolished) Didcot power station with its six massive cooling towers and central chimney stack as the setting for the crucifixion; Christ and the two thieves are set against the minatory bulk of the huge industrial buildings while other figures, lamenting and covering their faces, occupy the foreground. It is haunting and profound, an appalling vision but also a beautifully realised one – the work of a master of his craft.

For Wagner, art should never be ‘one person thick’. He believes in ideas handed down through the centuries

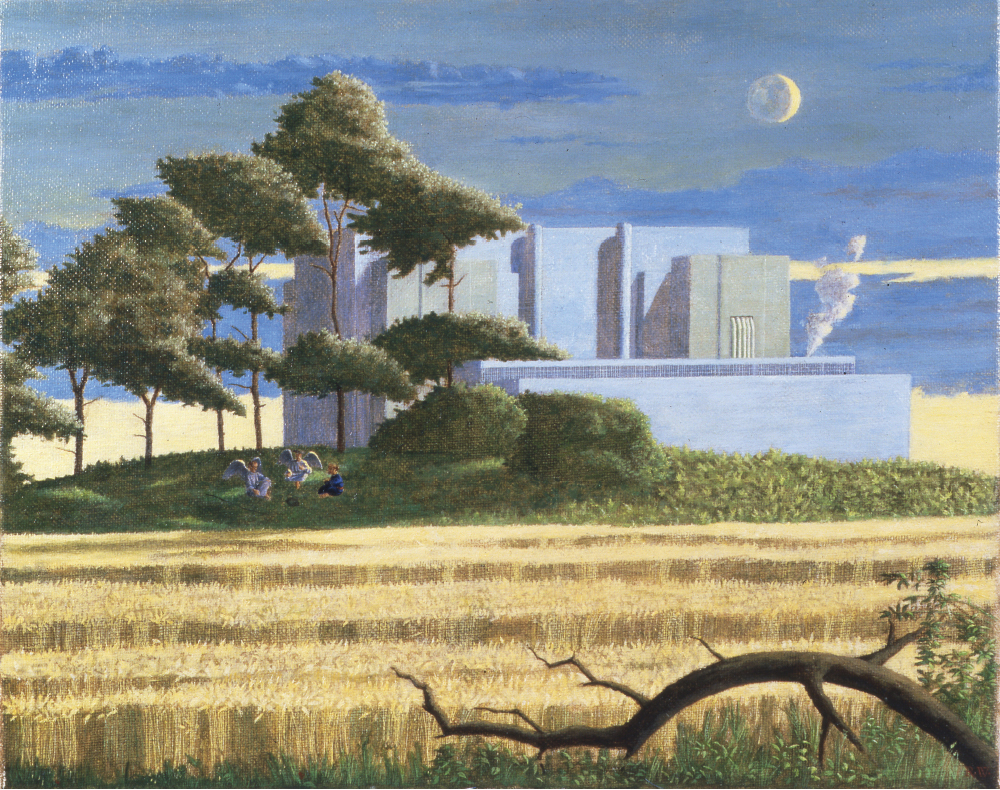

Roger Wagner, who painted it, is an Oxford man; he was educated at Lincoln College and has lived in the city ever since and the inspiration for the painting will be easily understood by anyone who ever travelled on the Oxford to Paddington line. Didcot power station used to be a familiar landmark on the way (until the drive for net zero did for it) and, as he tells it, he was on the train with his sketchbook one day when a particularly dramatic cloud formation framed the power station. ‘I think on paper,’ he tells me. ‘When I first saw Didcot power station through the window of the train… the smoke belching from the central chimney reminded me more of a crematorium than a symbol of God’s presence. And yet having said that, the astonishing sky behind the towers looked like the arch of some great cathedral, while something in the scale of the cooling towers themselves, with the light moving across them and the steam slowly, elegiacally, drifting away, created the impression that they were somehow the backdrop of a great religious drama. Both these ideas remained in my mind for many years, and developed in a series of paintings and sketches.’

When he showed the sketches to a friend they noted the likeness to the seven-branched candlestick: ‘Cups made like almond blossoms… the whole of it beaten work of pure gold’, in the words of the Book of Exodus. This was the menorah that Moses was instructed to place in the Tabernacle in front of the Holy of Holies. And it was the same menorah that was carried off in triumph by the Romans when they destroyed the Temple in ad 70.

‘Menorah’ was exhibited in the Ashmolean Museum, which later acquired the work and then loaned it to St Giles’ Church. The painting is probably the best-known of Wagner’s to date and established him as one of the country’s leading exponents of what is sometimes termed ‘religious art’, although that is a term he dislikes because it compartmentalises what he does without acknowledging the ancient connection between all art and religion. ‘In a sense there are no “non-religious” artists,’ he explains. ‘We are all trying to make sense of the world. It is a fundamental activity, not in any sense niche.’

Wagner walks in the footsteps of the long tradition of English visionary painters who have mined a deep vein of spirituality as inspiration for their work. Some of that work is among the best-known of all English art. The likes of William Blake, Samuel Palmer and Stanley Spencer have exerted an enduring influence on the English imagination. Despite the remorseless advances of secularism, their art remains popular, revered even, precisely because, unlike so much contemporary art, it speaks to things beyond the mere materiality of the world.

Blake has been a particularly important influence on Wagner. At Lincoln he read English but, nearing his finals, became seized by the idea that he should leave immediately and become a painter. He tells the story of how Blake claims to have received a direct instruction from God himself – ‘Blake: be an artist!’ – and says he felt similarly impelled, but the intervention of a kindly college chaplain dissuaded him from precipitately abandoning his studies. He completed his degree, then embarked on his apprenticeship as a painter. He learned his craft under Peter Greenham, then Keeper of the Royal Academy Schools, who told him that without the ability to draw, an artist is severely handicapped.

Wagner himself has taught drawing and laments how that skill has been downgraded in many art colleges. ‘If you don’t learn these things you are missing out on something which has been important throughout history,’ he says. ‘There are colleges which have almost persecuted the drawing school. These traditions are fragile; we need teachers who can draw.’ This reverence for tradition and traditional artistic skills means Wagner might be seen as something of a marginal figure in the inward-looking contemporary art scene. But while his work will never grace the walls of Tate Modern, he has found his own audience of those people who crave beauty and meaning.

Even Wagner’s paintings that aren’t explicitly religious are filled with a religious sensibility

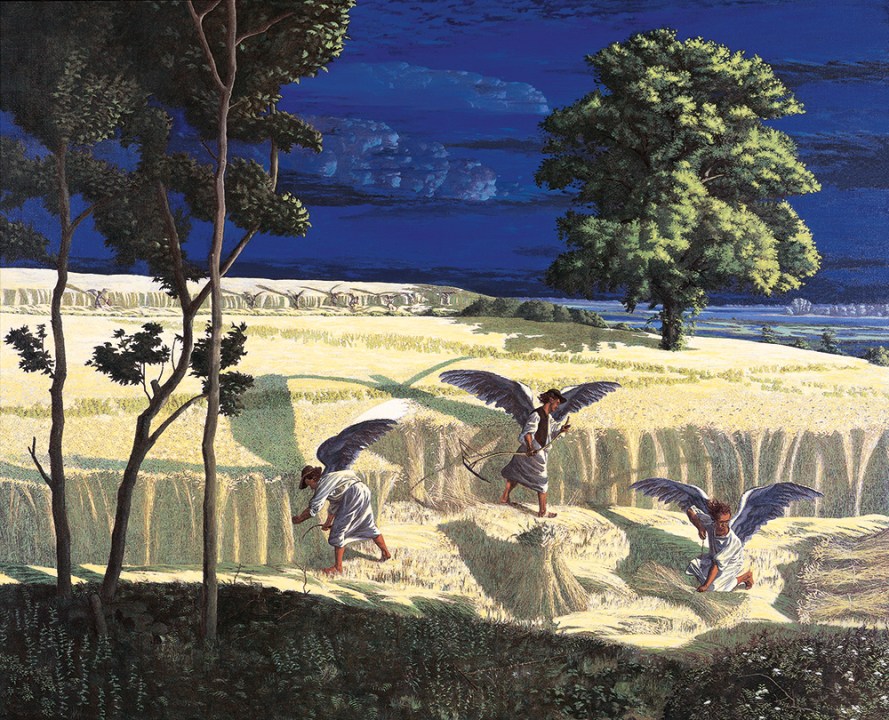

Wagner’s dealer and agent, Anthony Mould, says that what marks him out is that he appeals both to people who know a lot about art and to those who know little or nothing. It is the kind of art, one feels, which, though not ‘fashionable’, will never be out of fashion either. The fascination that Wagner’s paintings exert on his admirers can be quite overwhelming. At his exhibition last year at the Stanley Spencer Gallery in Cookham, one of the canvases on show was ‘The Harvest is the end of the world’ (1989). It depicts angels reaping an Oxfordshire cornfield; visually arresting – the yellow corn against a deep blue sky, the angels with their scythes – it is a depiction of the Last Judgment. I saw a woman standing before it, transfixed. When finally she turned, she seemed dazed; all she could manage was ‘so beautiful, so beautiful’. Wagner has that effect.

Wagner came under Spencer’s spell when, as a student, he attended the 1980 retrospective at the Royal Academy. Writing about that experience, he says that at the time it left him ‘deeply conflicted’ because ‘here was an artist who seemed to be doing exactly what I wanted to do yet who appeared to be going about it in entirely the wrong way’. Now he finds it difficult to remember exactly what it was about Spencer that caused a sense of unease: ‘I think I misjudged him. I was a very solemn young man. I think it was something about his almost jokiness that maybe put me off; there’s something of Beryl Cook about some of his work. But many of his pictures are marvellous; I have no reservations at all about the Cookham Resurrection.’ Certainly Wagner’s work is very different – there is none of the almost cartoonish, puckish humour that Spencer employs – but the commonalities between the two are irresistible. It is the insertion of the transcendental into the quotidian that links them.

Even Wagner’s paintings that are not explicitly religious seem freighted with a religious sensibility. His landscapes glow with a kind of all-seeing, divine hyperrealism. Talking about landscape painting he quotes John Constable’s remark that landscape is God’s own work. Wagner says that awe is a proper response to nature: ‘You can go into a landscape and it speaks of glory and wonder. God speaks to us if we allow ourselves to see it like that and then, I think, we are really seeing to the heart of things.’

So far outside the mainstream was Wagner’s work that, for many years, he struggled for recognition, explains Mould. But that is changing; his paintings are being acquired by institutions and collectors here and abroad. The St Ulrich Museum in Regensburg has some of his work and there is now a queue of commissions. There is also a permanent collection of his paintings at the Faith Museum in Bishop Auckland. His prices have risen accordingly, with a major commission costing up to £100,000. There is even a sign that his translucent, transcendental style is feeding into painterly fashions if you look at the work of Arcadia Missa’s Rosie Hastings and Hannah Quinlan, whose mosaics, recently installed at St James’s Park station, are very reminiscent of Wagner.

In person, Wagner is a modest and self-effacing character, careful not to condemn other artists whose work is so different from his own. But when pressed, he offers this opinion on the contemporary art world: ‘It’s difficult to see a vision in late 20th-century art. Innovation is not enough; you have to have something deep and profound you want to say. Why are we here? What is fundamentally important? If art is to have value it has to be part of a spiritual journey by the artist, which is what makes it so exciting.’

‘It’s difficult to see a vision in late 20th-century art. Innovation is not enough’

His own journey has led him to work in mediums other than paint. In another Oxford church, the tranquil St Mary’s in Iffley, he created a stained glass window of extraordinary beauty. Working under the tutelage of Thomas Denny, one of the country’s leading stained glass artists, the image he made is of the tree of life incorporating the crucifixion. He admits to having wrestled with whether it was theologically correct to combine these elements, but a visit to the 6th-century church of San Clemente in Rome reassured him. The apse mosaic uses the exact same ingredients. For Wagner, art should never be ‘one person thick’. Rather he believes in the power of artistic ideas that have been handed down through centuries: the life’s work of countless hands all striving to convey something larger than themselves.

Throughout his life, Wagner has written verse. In his twenties he published two slim books of poetry and images – printed on a treadle press and bound by hand – prompting the poet Peter Levi to comment that for Wagner, painting and poetry belonged together and that he should preserve that connection. In a few weeks’ time there will be a launch of his latest, The Farther Away: Poems and Images. The titles of this book and The Nearer You Stand: Poems and Images both derive from a line in Horace’s Ars Poetica: ‘A poem is like a picture: one strikes your/ fancy more, the nearer you stand; another, the/ farther away’. The former Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, called them ‘books of transfiguration’ which juxtapose ‘the familiar and unfamiliar, Syria and Oxfordshire, ancient and modern’.

Beauty is problematical if it is mere prettiness, says Wagner, for then it becomes escapist. Instead he seeks truth in beauty – in a world that seems to deny it. Many of his paintings depict the ugliness of modern industry but somehow redeemed. His work both disturbs and consoles, is freighted with deep meaning and glories in the wonders of creation. A painter for the ages.

The Farther Away: Poems and Images, by Roger Wagner, will be launched at St Andrew’s Church, Linton Road, Oxford, on 20 February, 7.30 p.m., as part of Songs in the Night: An evening of Poetry, Painting and Psalms. Roger Wagner: The Farther Away will be at MOMA, The Tabernacle, Penrallt Street, Machynlleth, from 14 June until 30 August.

Comments