In the Mellon Gallery of the Fitzwilliam is an unashamedly rich and demanding exhibition of Italian drawings, ranging from the 15th to the 20th century. I say ‘demanding’ because you need to look closely and with attention at these works — not simply to decipher what is going on (the narrative component), but to appreciate how it has been achieved (the formal aspect). So much of the stuff that is produced under the name of art today is easy on the eye and mind, with as much aesthetic nourishment as used air. Real art solicits the spectator’s involvement: it’s not a variant on wallpaper, it requires interpretation and response, intellectual as well as emotional. Drawings, being an artist’s first ideas, or evidence of the thought processes that result in a finished work, are especially vital and direct in their communication. We don’t have to have a detailed specialist knowledge of the period in which they were made (though this does help) — what we need more is an open and receptive eye and an inquiring mind.

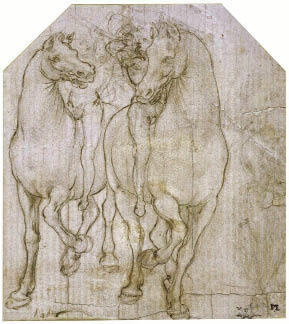

Drawings are fragile and particularly susceptible to the deleterious effects of sunlight, so the gallery is dimly lit and the ambience suitably reverential. Out of the gloom comes a wild boar by Pisanello: snouty, tusky and questing, drawn in black chalk and ink. This swift access of living reality is confirmed in the drawings of another great master — Leonardo, represented here by a trio of studies. There’s a beautiful metalpoint of two horses seen head-on and a moving depiction of the ermine as a symbol of purity, caught by hunters who block up its burrow with mud, knowing it will not sully its spotless pelt by attempting to go to earth. (This drawing might have been made as a design for a hat badge.)

Then there’s a highly effective grouping of figures in a drawing of the Holy Family by Parmigianino, and in a corner a study of two standing women by Perino del Vaga. Done in pen and wash, with small heads and great statuesque bodies, this has something of the monumentality of Henry Moore.

In a flat cabinet nearby are a couple of Raphael drawings, one in pen and brown ink, the other in red chalk, that are unexpectedly inquiring for such an assured artist, both exploring ways of representing groups of figures interacting. Moving on to Venice in the 16th century, we are offered Vittore Carpaccio’s telling evocation of two groups of ecclesiastics facing one another, roughly scratched in with brown ink and given body with red chalk, though in fact the chalk was put on first. And here’s a lovely sexy Titian drawing of an embracing couple, in which the bodies — drawn with caressing strokes of charcoal — seem to be moving and melting into one another.

Then there’s a Michelangelo sheet showing a draped figure of Christ, in which the black chalk is gently stroked into the paper, like smoke solidifying into form; expressive and emotional rather than linear and declarative. I enjoyed the group by Annibale Carracci: the large head of a bearded man in red chalk, looking a little like D.H. Lawrence; below it a black chalk study of the head and torso of a male nude; to the left a fabulous pen and brown ink ‘Adoration of the Shepherds’, a large and complex drawing, vigorously dynamic.

A wild and vibrant Guercino drawing comes next, with singing single lines coalescing into darker knots of passion, the subject being ‘The sleeping Rinaldo abducted by Armida’. On the opposite wall is a more illustrational drawing by Magnasco in pen and brush of a standing singing man with a musician. Dramatic and engaging, this works partly through distortions of scale and collapsing of space.

Other artists create mood and meaning through the areas of paper left blank between the scratchy lines and the flow of brushed ink, such as Luca Giordano in ‘Christ at the marriage of Cana’. This technique can be seen in even more extreme form in Luca Cambiaso’s ‘Angel blowing a trumpet into St Jerome’s ear’, in which the areas left blank are made to work as hard as the drawn ones.

Among the other treasures that I feel impelled to mention (and there are many more works of varied appeal) is a splendid large Guardi ink drawing of the Grand Canal in Venice, all energetic lines and rags of dark and light, and no fewer than eight Tiepolos. (I loved the drawings of houses and the three male nudes on clouds.) I was not so moved by the Grand Tour vision of Marco Ricci and Francesco Panini but, of the more modern works, particularly fine is the Indian ink and wash ‘Portrait of a bearded man’ by Modigliani, bequeathed to the museum by Lillian Browse.

The rewards of an hour’s concentrated looking are immense. If you have any energy left over, the adjoining displays of modern art — in particular, a group of Nicolas de Staël’s paintings, a fine Morandi landscape and a magnificent Roger Hilton abstract from 1959 — are well worth a visit.

Thirty-five years ago, the American painter R.B. Kitaj, at that time living in London, organised an Arts Council exhibition of contemporary figurative art entitled The Human Clay. It was a manifesto exhibition promoting a ‘School of London’ — painters who were seriously interested in drawing the figure.

Kitaj’s original selection numbered nearly 50 artists, some now well known, others who have slipped off the radar, such as Richard Carline and Philip Rawson. Subsequently, the School of London came to mean only a handful of artists: Kitaj himself, Michael Andrews, Leon Kossoff, Frank Auerbach, Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud. Various others were attached at different times by writers or exhibition organisers, but that core has held. James Hyman, an art historian of British figuration as well as a dealer, now examines Kitaj’s original exhibition and opens up the field once more to include a wider range of artists.

Hyman’s show falls into two parts: a selection of Kitaj’s original choices, and a group of works by other artists for whom drawing is important. There are notable omissions: nothing by Maggi Hambling, Ken Kiff or Paula Rego, but there are also compensations. The display is built around a classic early Kitaj from 1961 called ‘The Bells of Hell’, a wonderfully lucid modernist account of the Battle of Little Bighorn seen as a ‘Cowboys and Indians’ and heads-bodies-legs assemblage. Next to it are a darkly potent Kossoff self-portrait and an elegiac Dennis Creffield drawing. A large Peter de Francia allegory from c.1970 contrasts keenly with the extraordinary ‘Night Interior with Lay Figure’ by Lewis Chamberlain, one of the most fanatical pencil drawings I’ve seen.

There are a couple of Colin Self’s inimitable studies of people and three small but luscious Basil Beattie oils of his familiar repertoire of forms: steps, ladders, tunnel. In the back room is a surprisingly delicate early nude drawing in ink by Euan Uglow and Robert Medley’s brilliantly minimal portrait of Philip Prowse.

Hyman has produced a catalogue, which echoes Kitaj’s original 1976 publication, in which he writes lucidly of the School of London and subsequent artistic responses to the High Art seriousness of Kitaj and his colleagues. With this intriguing show, James Hyman celebrates a decade of staging often challenging and always stimulating exhibitions of British figurative art.

Comments