Dan Hitchens has narrated this article for you to listen to.

The Pentecostal preacher is in full flow – his voice raised to near-deafening volume, his gestures expansive but exact, the congregation murmuring back a chorus of ‘Amens’ – when he receives an unexpected interruption. ‘A woman asked me at the barbecue last week,’ he is telling us, ‘“Pastor, if I won the Lottery…”’

A voice somewhere to his right intervenes. ‘A-MEN!’

A wave of laughter from the congregation. The preacher rides it. ‘No! Don’t Amen that! We don’t believe in lotteries, we believe in work. Hard work. So, she asked me, “Pastor, if I won the Lottery, and I gave the money to the church repair fund, would you accept it?” And I said…’

The congregation is quiet again. We’re in the realm of moral theology.

‘Of course I would! Does that mean I want you to play the Lottery? Of course not!’

Communities which make serious demands are more likely to inspire serious commitment

It’s Sunday morning at an Elim Pentecostal church in London, and the place feels alive – fittingly for perhaps the fastest-growing Christian community in the UK. Over the past 25 years, Elim’s membership has risen from 50,000 to 75,000, according to the statistician Peter Brierley. The figure is striking when you consider the overall picture of Christianity in the UK. The census revealed that, for the first time, less than half of the country identified as Christian, a fall of seven million people over a decade.

Yet while certain kinds of Christian practice are fading, it seems, others are very much not. In recent decades, thousands of new churches of all varieties have sprung up across the country; London’s Sunday attendance is 10 per cent higher than 40 years ago. Vast congregations have flourished if you know where to look.

John Hayward, a former maths lecturer, has produced a model to try to track which churches are growing and which are shrinking. He focuses on the ‘R’ number – made famous by the pandemic, but long employed by statisticians for anything that spreads through person-to-person contact: rumours, internet trends, social contagions such as bulimia, urban riots. Put simply, if churches aren’t making more Christians than they are losing, the R number falls below the crucial threshold of 1, and decline sets in. He has published a study of UK church groups which makes for sobering reading.

Hayward’s own congregation, the Church in Wales, is declining at such a rate that – on the assumption that nothing changes – it will be extinct at some time in the 2030s, just after the Welsh Presbyterians. In the 2040s, it will be the turn of the Scottish Episcopalians, Methodists and the Church of Scotland. The last rites for Anglicans and Catholics will be read in the 2060s.

The more charismatic and evangelical churches, such as Elim, Newfrontiers and the Fellowship of Independent Evangelical Churches, have a healthy R rate. Everyone else is below the line.

Hayward acknowledges that immigration is a huge factor in the growth of churches. But he tells me that growth, once established, can go on ‘for generations, and it pulls in other people. I was at a meeting the other day with representatives of Nigerian churches, and the majority of their congregations are not immigrants.’ Growing communities, he says, don’t just make believers, but ‘disciples’, who are able to pass on the faith to others – to infect them, you might say. ‘Successful churches teach people how to introduce others to the faith, and to show them how to be a Christian.’

All that you can see on a Sunday morning at Elim Pentecostal. The emphasis on spreading the faith is relentless: the faithful are reminded to talk to people about Jesus every day, and encouraged to attend an evangelisation seminar later in the week. There are disciple-making workshops, too, for ‘Men of Valour’ and ‘Women of Substance’. In a small congregation of around 70, about ten have a serious role in the service – leading prayers or whatever – and everyone does so with confident enthusiasm.

Moreover, the service has the feeling of a family reunion. Everyone knows when to join in. There is raucous laughter at in-jokes, and when the service pauses for five minutes of greeting each other, the room turns into a whirl of hugging and backslapping. Half a dozen people come over to warmly introduce themselves. As a dogmatic Catholic of the old school, I am not seeking answers to the big questions. But if I was, I might think this was a good place to look.

Thriving churches, Hayward says, ‘are very intentional about what they do. They are very clear in their beliefs’ – particularly about the urgency of accepting Christ, since one’s eternal destiny is at stake. ‘Rather than, “Well, everybody here believes something, and we’re not really sure what, but we can always put on an event and maybe somebody will come along.”’

A week after my visit to the Pentecostals, I attend a service at a United Reformed Church – which is the fastest-declining of any UK-wide church. The service is led by the Moderator of the URC, the Revd Dr Tessa Henry-Robinson, described by her church as ‘a womanist practical theologian’ who has a particular focus on ‘uplifting ethnically-minoritised women and communities’. The URC itself, according to its website, ‘is not rigid in the expression of its beliefs, and embraces a wide variety of opinions’.

The Gospel reading is about forgiveness: a ‘contentious’ subject, Dr Henry-Robinson concedes in her sermon, but ‘we can begin almost immediately by asking forgiveness for how we buy into containing and using God’. Such as? Pronouns, apparently. ‘I am not asking people to be on the same journey, but I am trying to be intentional about not using “he” or “she” or “it” or “they” to identify God… not limiting our language in identifying a God that is limitless.’

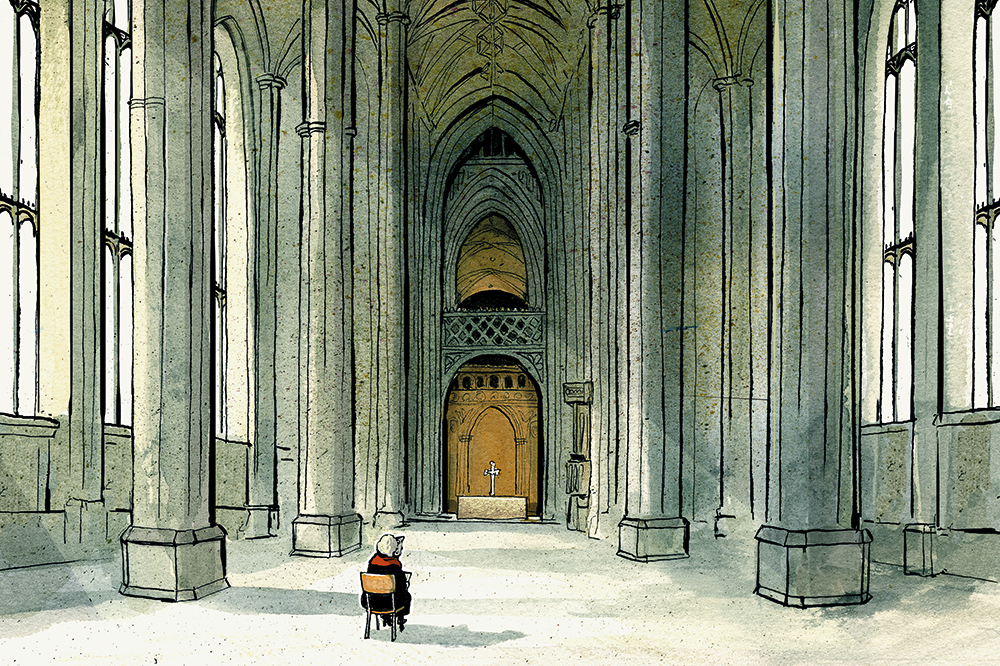

The trade-off is that so limitless a God may also be too fuzzy to see clearly. At the back of the Elim church is a cross, a reminder of Jesus’s saving death. At the back of the URC church is a stained-glass depiction of a tree with tongues of fire in it, a general image of life and renewal.

One theory is that communities which make serious demands are more likely to inspire serious commitment. In Britain, at least, that theory has recent history on its side. The Anglican vicar David Goodhew, a leading researcher of church growth, summarised the evidence: ‘Those trimming faith to fit in with culture have tended to shrink, and those offering a “full-fat” faith, vividly supernatural, have tended to grow. This is as true of the ultra-liturgical Orthodox as it is of the ultra-informal Pentecostals.’

The plight of Anglicanism is acute. Just 3 per cent of under-25s describe themselves as Anglican. Last week, Justin Welby said it might not be ‘all bad’ that ‘faith has declined dramatically… I rejoice in less of a bossy attitude, and of the church stepping back from telling everybody what to do.’ A church which doesn’t tell people what to do may, as Welby implies, be learning a new humility. Or it may just be suffering a fatal loss of confidence.

In which case, should the big, shrinking churches copy the smaller, growing ones? Stephen Bullivant, professor of theology and the sociology of religion at St Mary’s University, Twickenham, points out that the comparison is somewhat unfair. ‘Catholics and Anglicans tend to see themselves as being for everyone, and therefore have to expend their resources everywhere at everything.’ Smaller groups can target a particular ‘market’ – say, by planting a church near a university with a big immigrant population. Nevertheless, Bullivant argues, the bigger churches should learn something from this: it is worth picking out groups with strong identities and allowing them their own space, rather than assimilating everyone into a model that ‘suits no one exactly’. The Catholic Church, for instance, has given whole parishes to traditionalists or to the Ordinariate, which uses an Anglican-style liturgy. These parishes then attract enthusiasts from miles around. Another fervent community, the mostly Indian-born Catholics of the Syro-Malabar Rite, have since 2016 had their own bishop at the head of their eparchy – a kind of parallel diocese.

The smart strategy, Bullivant says, is to lean into such diversity, giving confident communities ‘a chance to build something that lasts’. But the clergy may be reluctant to get on board. ‘No bishop wants to lose a good chunk of the most practising Catholics he has to the Syro-Malabar eparchy. And no parish priest wants to give up the three big practising families who would look after the Confirmation classes and provide such excellent food at parish functions. That’s not a joke, by the way.’

Comments