The first time I heard a piece of music by Erik Satie it was on the B-side of a Gary Numan single. Played on a synth that sounds like a theremin sucking on a dummy, ‘Gymnopédie #1’ is so saccharine sweet it actually makes the music seem sorry for itself. And yet. It got me hooked on Satie’s catchy yet sombre ironies. Par for the course, says Ian Penman in this dazzling study. People who know nothing about music beyond the top tens of their teens can be so ‘instantly beguiled, captivated and transported’ by Satie that his ‘pop single length’ works are ‘now part of some collective audio memory’.

Those who know nothing much about music can be instantly beguiled, captivated and transported by Satie

For all that, there is no mention of Numan here. Nothing strange, you’re thinking – but get a load of those who do turn up in the book. Ravel, Debussy and Poulenc are present and correct, of course. And since he studied composition under Satie’s pal Darius Milhaud, I guess Burt Bacharach was a shoo-in for a look-in. But how about Stevie Wonder and Elton John? The Keiths, Jarrett and Emerson? The Evanses, Bill and Gil? It’s Sunday Night at the Penman Palladium! Bring on those stars of stage and screen! Satie’s double act with Francis Picabia in René Clair’s comic silent Entr’acte ushers in a reverie on Morecambe and Wise, Pete and Dud and Vic and Bob. Satie came from Normandy and was rarely seen without an umbrella – give a big hand to Jacques Demy’s Les Parapluies de Cherbourg. Yet none of this scattershot name-dropping is facetious, much less otiose. Even Penman’s recollection of Les Dawson’s version of ‘Feelings’ serves to point up the wit that underlies so much of Satie’s music.

You’ll have gathered that this book, which is being published to mark the centenary of Satie’s death, is no garden-variety monograph. Indeed, since it really does have three parts – a vaguely conventional essay on Satie’s life and times; an A-Z of all things Satie; and a diary of the last few years in which Penman has jotted down Satie-stimulated hunches and hypotheses – we might do better to call it a triograph. But there’s no way of shelf-marking a book like this. Dismissing the conventional biography for being ‘too linear – as if modernity never happened’, Penman is trying, like his film director hero Nicolas Roeg, to engender a whole new form.

The result is something that looks more like a screenplay than a critical tract, with as much white space as black ink. Aphorisms and apophthegms – many of them so brief they occupy only a line or two – ladder the page like a John Coltrane chart. No attempt is made at logical, step-by-step argument. Penman’s points rarely relate to one another and certainly don’t flow in any order. Not that he’s being lazy and making his readers do the work for him; he wants to get ‘people… out of the habit of explaining everything’. Satie’s minimalist phrases, shimmering, impressionist harmonies and cubist rhythms play havoc with convention – he wrenches time about in just the way the canvases of his chums Picasso and Braque reconfigure space. Similarly, Penman wants to undermine the commonplace that criticism must cohere to convince.

Satie’s aesthetic was so influential, Penman believes, that it gave us the sound of the contemporary world. He invented the ambient music that Michael Caine loves (Satie called it ‘household music’); the industrial music of Lou Reed and Kraftwerk; and full-on muzak (an insulting name that is somehow outdone by Satie’s original idea of ‘furniture music’). Whatever the truth of these claims – and surely the bombast and braggadocio of what Penman calls ‘big puffed-up symphonies’, ‘self-important concertos’ and ‘sweaty drama-queen conductors’ have had some sway on rock and pop, too – they licence some stunning aperçus. Satie makes us ‘attend to the forgotten realm of quiet moments’; an encyclopaedia is ‘a largely successful attempt to keep chaos at bay’; Harold Budd’s ‘Luxa’ is ‘lift music for a lift that never goes up or down’.

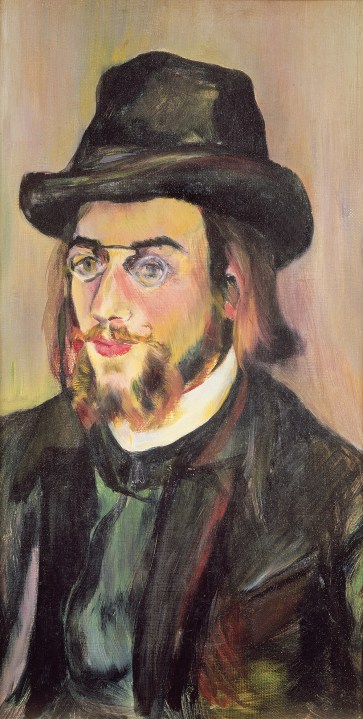

No, I haven’t heard of that either. But then, if nothing else, this book leaves you with a playlist that will take weeks to work through. And be in no doubt: you’ll want to hear what Penman’s heard. His bibliography is brief to the point of pointlessness, and some reproductions of the images he is so fond of discussing would have been nice. But really, what more can one ask of criticism than that it turn you on to stuff you’ve never seen or heard?

Comments