Ciaran Carson was born in Belfast in 1948, and published his first book of poetry, The New Estate, in 1976. Fans of Carson had to wait eleven years for his second book, The Irish for No (1987), which earned him the Alice Hunt Barlett Award.

Belfast Confetti (1990) won The Irish Times Literature Prize for Poetry. In 1993 Carson won the first ever T.S. Eliot Prize for poetry, for his collection, First Language; while his 2003 collection, Breaking News, won the Forward Poetry Prize. That same year, Carson was appointed Professor of Poetry, and Director of the Seamus Heaney Centre for Poetry, at Queen’s University in Belfast; a position he has held since.

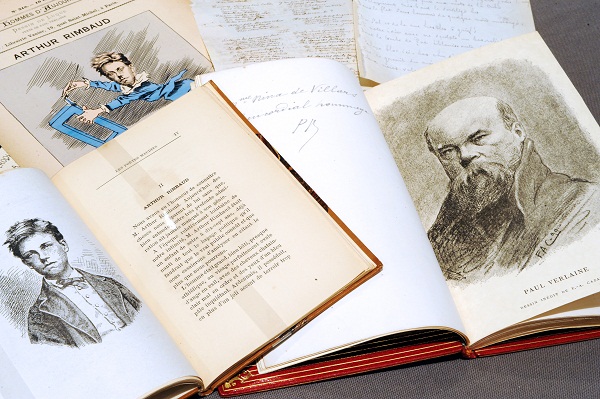

Carson has also proved himself to be an accomplished translator. In 1998 he published adaptations of sonnets by Rimbaud, Baudelaire, and Mallarmé, in The Alexandrine Plan. His version of Dante’s Inferno in 2002 was awarded the Oxford Weidenfeld Translation Prize. Carson’s latest collection, In The Light Of, displays twenty-two verse interpretations, as well as three prose versions, of the prose poems from Rimbaud’s Illuminations. It is generally believed that the original manuscript of Illuminations was written sometime between 1872 and 1875, in various locations including London, Paris and Belgium. The poems may also be the last Rimbaud ever wrote.

Carson spoke to The Spectator about the art of translation in poetry, the value of storytelling for a poet, and why defining a poem can limit its very purpose.

Should we see these translations for their evocative, dreamlike quality rather than their literal meaning?

‘Literal meaning’ is a problematic phrase when it comes to translations of poetry. The temptation with Rimbaud’s Illuminations, because the pieces are ostensibly in prose, is to render them more or less word for word, thus ignoring their music. But the more you examine them, and read the French aloud, you can see that the prose has metre, and occasional rhyme embedded in it. They are indeed prose poems; I think Rimbaud invented the genre. Any translations I had read seemed flat and inert to my ear, so I decided to rewrite them in the rhyming couplets of the classical French alexandrine. Without that constriction of form, I could get no angle of attack on the material. I wanted the dreamlike imagery to rhyme, chime, and echo: to make some kind of music to my ear.

How heavily did you lean on previous translations that exist of Illuminations for this project?

I began by working from Louise Varèse and Oliver Bernard’s translations. I also looked at several others, including John Ashbery, who I had been an admirer of, but I was disappointed with his take on Rimbaud, which I felt was ponderously literal and flat. But all the translations I read helped me in one way or another.

Can we see what Rimbaud was trying to express in Illuminations, as both his horror, and fascination, with the 19th Century city?

I don’t know if ‘express’ is the right word for what Rimbaud was doing; that word implies that the poet begins with some kind of manifesto, which he then illustrates in poetry. The poems are visceral reactions: they come out in their own weird and zany logic. In retrospect, we can read some of them as critiques of industrial society. Rimbaud was fiercely anti-respectability, and took a certain delight in squalor, therefore his reactions to the horror and opulence of cities is indeed complicated.

Is trying to find definite meaning in any poetry a futile exercise?

The kind of examination question which used to be put, ‘What did the poet have in mind when he said…’ is an assumption that the poet clothes his thought in verse, whereas, the poet often doesn’t know what he has in mind: he follows the language, and sees where it might lead him, which is usually a very different place from what he thought at the onset. If you know exactly what you are going to say in a poem, that poem will be a failure. Besides, there is no interest or fun, in saying what you already know. Poems are devices for learning what you never knew until you wrote the poem. They take you elsewhere. Rimbaud’s poetry certainly does anyway: into a world that is eerie, strange, and fantastic

In your introduction to In The Light Of, you quote Walter Benjamin, who writes in The Task of the Translator that ‘[the translator] must expand and deepen his language by means of the foreign language’. When you were translating these poems, did you feel there were elements that had to be reinvented in English?

When reinventing, one must find another spin on the language: it’s more a renegotiation, perhaps, than a reinvention. Subject matter, Benjamin implies, is only one aspect of a text, be it prose or poetry: besides the music of the matter, there is the fact that words apparently similar, can carry different cultural gravities in different languages.

Could you talk about parallax, and how objects change from one state to another in these poems? For example in ‘Invisible Cities (Les Ponts)’, the poem cuts into an analogical city of music…

Rimbaud is all analogy: one thing continually leading to, or becoming another. It’s one of the attractions of Illuminations that one never quite knows where one is. A seemingly familiar landscape shifts into something bizarre; one is always pleasantly estranged, as one might be on a good drugs trip. Did you feel that changing the prose poems in Illuminations into verse, worked the language into a cadence where everything is cinematic and moving at all times, in terms of how it animates the landscape of the poems?

Yes, the verse was key to the whole project: the poems do move in a very cinematic way. It seemed to me that if I did put them all into English prose, it would take away from that dynamic energy. The constriction of the verse pushed me to find ways around the poems that I wouldn’t have done otherwise.

In your 2003 collection, Breaking News, your work became very urgent, with particular emphasis on the stress of the ultra-short line. The style has echoes of William Carlos Williams. How influential was he for that collection?

I loved the freshness of Carlos Williams when I first read him back in the late 1960s. You’ll note that the only poem in Breaking News directly attributed to Williams ‘The Forgotten City’, is written in a somewhat conventional line, much the same line as Williams used in that poem. My take on it was to move the location from an American city to Belfast: a literal translation, if you will, since ‘translation’ literally means to move something from one place to another. I had written quite a few of the short-line poems before I realized they were in the Williams mode, hence the tribute.

My poems were informed by an anxiety not necessarily present in Williams: the anxiety of a still troubled post-ceasefire situation, in which silence can speak as menacingly as any words. So the poems are full of hesitations, gaps, and broken syntax. That’s not to say that I was writing to that kind of agenda: one writes the poems, and figures out what they might be about in retrospect.

The Troubles in Northern Ireland, on occasion, has been the subject matter of your poems. What effect, if any, did the poems have in helping you understand the nature of the conflict?

I don’t know if poetry does anything for one. It’s not about exorcism. It’s not that kind of medium. One writes because one has to, without any thought of what it is for, or even what it might imply. It’s about looking into the language to see how it might apply. Apply to what? Perhaps it’s a matter of the questions. Poetry doesn’t have any answers, but it does have lots of questions. It provides a questioning dimension to our lives.

Why did you choose to write with such directness when it came to depicting acts of violence in The Troubles? Take for example the poem ‘Campaign’. ‘The bad smell he smelt was the smell of himself. Broken glass and knotted Durex/ The knuckles of a face in a nylon stocking.’

That poem is a documentary of a kind, based on an actual incident. I don’t think I had any political axe to grind in poems like this: I thought of myself as a recorder, a camera, or a fly on the wall, registering what was going on around me. Some of the poems are done with a black Belfast humour that was very much in vogue then. In a war situation everything tends towards the surreal: horrifying, yes, but also blackly comic or absurd. I didn’t think of myself as not holding back. In a strange way, I only did what I was being told.

Could you speak about incorporating the vernacular into your poetry? I’m thinking of a poem like ‘Dresden’. ‘Horse Boyle was called Horse Boyle because of his brother Mule;/ Though why Mule was called Mule is anybody’s guess.’

At the time I wrote that particular poem I was deeply immersed in playing and learning music and song, which took me on rambles around various parts of Ireland. The speaking voices in the collection, The Irish for No, were to some extent based on the storytelling of the late John Campbell, whom I acknowledge in that book. What I loved in the sessions I encountered was the fluid mix of music, song, chat, anecdote and story, not to mention drinking. It seemed there was no fixed line between those genres, or between art and life. That was enormously refreshing and interesting to me, how apparently ordinary speech can, within a couple of turns, become a story. And I wanted to write poetry that corresponded to all of that.

Comments