The online accessibility of British population censuses has resulted in an outpouring of ‘who and how we were’, keeping amateur genealogists, local historians and social commentators extremely busy. Barry Anthony’s book relies heavily on the censuses of the late Victorian and Edwardian years, combined with a close reading of the astonishingly detailed stage magazines and papers such as the Era and the Entr’acte, to flesh out what we know of the early life of England’s most famous comic actor.

Charlie Chaplin’s stage career was not long; he seems to have seen, in some flash of foresight, that film was the coming medium and by 1914 he had transferred his gifts from theatre to screen. But one of his great late films, Limelight, released in 1952, is entirely rooted in his experiences of the London music halls of his youth.

The chapters of this book are on the formative figures around the young Chaplin — his mother, his father, their friends and relations, all of whom were performers in the halls. Most are obscure and the author demonstrates dogged research into the dilapidated outhouses of music-hall history.

It is an unedifying picture of minor ‘stars’, neither big enough to maintain a public following over a long period nor sharp enough to adapt to the quick-changing fashions of the ‘old’, intimate music hall as it became swallowed up by the big and brash Variety Theatre. Their tiny flames are only kept alive by aficionados of the halls such as Anthony, who piles up the squalid details of drink, violence and dissolution.

The scene for most of these south London catastrophes was Kennington Road and its environs. This was the favoured location for the underbelly of the halls: it was near the theatre agencies in Waterloo and popular halls such as the Canterbury, Gatti’s and the South London Palace. Rents were cheap and the area was strewn with pubs. Magistrates’ courts were kept busy; early deaths and suicides were commonplace. It is the world evoked by Somerset Maugham in his first novel Liza of Lambeth.

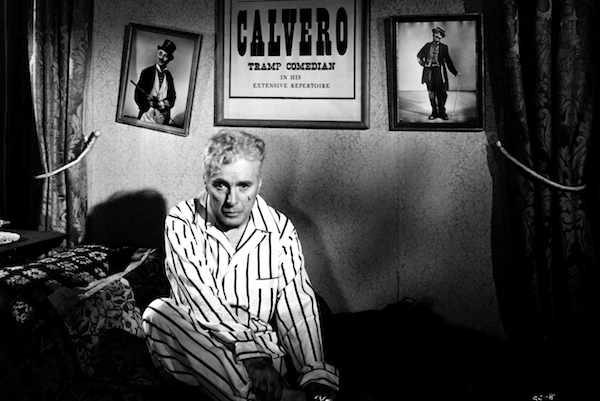

Chaplin recounted his memories of this period and the artistes he knew in a long, unpublished ‘treatment’ in readiness for his eventual film. Limelight’s protagonist, Calvero (played by Chaplin) is a composite portrait of his father, also Charles Chaplin, a singer, and Leo Dryden, a performer of descriptive and narrative songs, who fathered Charlie’s half-brother Wheeler Dryden. Some sources, including Chaplin himself, state that characteristics of another performer, Frank Tierney, fed the portrait, but Anthony does not mention him.

Chaplin senior, who had some success in the halls, was an aggressive alcoholic who abandoned his family and died in 1901 aged 38, a vast, dropsical figure with, at his death, only a half sovereign to his name, hidden in his slipper. Chaplin’s mother Hannah had a brief singing career as Lily Harley before poverty, finding God and mental illness took over; for her, bad times were always round the corner. But she had a certain sweetness and humour, particularly as a mimic, something her son had in abundance. From spells in various South London asylums she was eventually taken to California where she died in 1928 in the luxury of care provided by her then very well-off son. Born Elephant and Castle; buried Hollywood.

In his autobiography, Chaplin passes over several people from whom he learned his comic craft. Anthony is at pains to redress these omissions, and chapters are devoted to influential figures, such as ‘Dashing’ Eva Lester, the prolific songwriter Will Godwin and the briefly celebrated ‘Topical and Extempore Vocalist’ Arthur West. It is here that the author adds his mite to the Chaplin phenomenon. But the book wears its research on its sleeve, some of its pages choked with a flat-footed account of names and dates.

In Limelight the re-creation of the theatre of Chaplin’s youth is seen through retrospective elaboration. Nevertheless, anyone who remembers, towards the end, the superb scene of Chaplin and Buster Keaton duetting on stage can be assured that this is true music hall in which Chaplin’s every physical gag and facial tic is a masterclass in ‘how it was’.

Comments