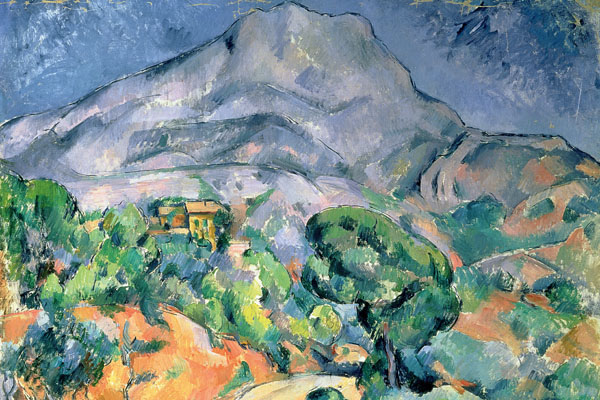

Like Mont St-Victoire itself, looming over the country to the north of Aix-en-Provence — seen unexpectedly, then just as suddenly hidden, now clear-cut against the sky, at other times a presence in the corner of the eye— the work of Paul Cézanne has been a landmark in the art of the century and more since his death in Aix in 1906. Unlike Monet, Matisse or Picasso, his influence in his own lifetime was restricted to a small circle of admirers — mostly in the last decade of his life. It is an unusual occurrence for so crucial a figure in the history of painting to have gained a reputation that was almost entirely posthumous.

Before 1906, Cézanne was frequently regarded as a curious minor contributor to the Impressionist movement, in early accounts of which he is referred to only briefly or disparagingly. If Camille Pissarro, in the 1870s, had seen Cézanne as the ‘genius of the future’, it was only in the wake of Cézanne’s death and in subsequent decades that the truth of the phrase became abundantly apparent. Innumerable artists looked to his achievement for guidance and inspiration, some scaling its heights with confidence, others content to nestle in its shade. Cézanne became all things to all artists and, whatever the prevalent aesthetic climate, he remained exemplary in his single-minded integrity, ‘a comfort and support, such as a board provides for the bather’, as Cézanne himself wrote of his reliance on the art of the past that he admired.

When we turn to the literature on Cézanne — to which Alex Danchev’s book is an exceptional contribution — almost from the start the field is remarkable for its diversity and interpretative breadth. It moves from early personal memoirs to exacting formalist analysis, from the vivid responses of artists to the niceties of the catalogue raisonné, from the photographing of Provençal motifs to the limitless shores of psycho-biographic speculation (the apples=breasts school). Such abundance reflects not only Cézanne’s accepted stature but also his mercurial temperament as it inflected his painting and contributes to that sense of his work as still being enigmatic and elusive and yet extremely popular.

Something of this unfathomableness is conveyed, for example, in many of the letters he wrote in his last years. The small beer of domestic detail is abruptly juxtaposed with searching formulations about his progress that have exercised, even tormented, interpreters of his art ever since. An indefatigable egotism goes hand-in-hand with self-abasement. Suddenly, the epistolary formalities of the age are subsumed in the violent expression of his state of mind.

The eternal problem of the artist’s necessary self-absorption versus his or her domestic, social and political responsibilities runs through Cézanne’s life with increasing agitation. Danchev makes this a compelling thread of his narrative. At first, however, we find a Cézanne who, farouche and sometimes difficult, was nevertheless sociable and eager to take part in the momentous upheaval of Impressionism in Paris. He came to know nearly all its main players and formed particularly close friendships with Monet, Renoir and, especially, Pissarro, all of whom recognised his early potential and, years later, saluted his great achievements.

But there was one intimate who begged to differ — his old schoolfriend from Aix, Emile Zola. Danchev is very perceptive on this crucial relationship and its eventual dissolution, soon after Zola published L’Oeuvre (1886), the novel in which Cézanne is partly the model for Claude Lantier, the failed painter of enormous promise, who hangs himself.

Cézanne’s contemporaries were disturbed by this portrait, for it seemed to them an indictment of the whole Impressionist effort of which Zola had earlier been so supportive. As Danchev stresses, we do not know Cézanne’s reaction to the book, but from then onwards he no longer saw Zola and there was a gradual withdrawal on Cézanne’s part from Impressionist affairs. Although he continued to visit Paris and paint there (and to see his wife and son who lived there for increasingly long periods), Aix became his refuge. His father, a banker, left him sufficiently well off for Cézanne to be able to afford his solitude and follow his ‘sensations’.

By the 1890s, a circumscribed celebrity came his way; he was visited by young admirers to whom he felt an urge to convey his thoughts (in talk or writing) on painting, on the old masters, on his contemporaries. Often gnomic and elliptical, they also contain enough of truth and logic to convey an aesthetic programme of real conviction. When these thoughts and letters were published soon after his death, they provided an influential credo that is among the most potent of any artist’s self-revelations. The legacy of the sage of Aix took hold.

But running parallel was a generally unflattering portrait of the artist that gained in currency — of an anarchic, ill-bred Provençal of reactionary opinions, with a serrated edge to his dealings with people. Over the decades this portrait has been largely vanquished. Danchev, consistently revisionist throughout, does not avoid elements of this part-caricature but he tenderises the meat of Cézanne’s personality.

Cézanne poses a particular challenge for a biographer. Unlike his friends and contemporaries such as Renoir, Monet or Pissarro, he is not abundantly documented. An irascible character riven with contradictions, he is not an easy subject for a writer to tease into any psychological pattern; and his painting, after wild beginnings, is relatively free of autobiographical disclosure (here Danchev is refreshingly sceptical of interpretative psychobabble).

And yet, because of the dearth of material, his life has been subject to intense scrutiny and even now, as this fully researched book reveals, nuggets of information are unearthed. The chief merit of Danchev’s biography is not any startlingly new material but its excellent synthesis and analysis of known accounts, presented with unfailing probity, to build a highly convincing and sympathetic portrait.

If Cézanne is not the most captivating subject in terms of romance, disaster, exoticism — for these we go to Van Gogh, Gauguin or Toulouse-Lautrec — his life is profoundly moving to anyone who follows the painful trajectory of, in Sickert’s phrase, his ‘gigantic sincerity’. And this is what Danchev has accomplished so well.

Comments