Early American settlers said that a squirrel could climb up a tree on the coast of Massachusetts, set off westwards and not touch the ground until it reached the Ohio river. The squirrels, like the Native Americans, were pushed out and west. Timber was the settlers’ main resource, and they stripped New England of wood for their farms, buildings and fuel. Today, after decades of rural depopulation and second-home gentrification, New England may well have more trees than at any time since the 1830s. But the wooden world of early America is gone, like the Native Americans.

As the Cherokee were forced on to the Trail of Tears, they marked their passage by a trail of trees

Haunted, weird America, the America of Nathaniel Hawthorne and Edgar Allan Poe, started to become mass-produced industrial America in the 1830s. The Forest is Alexander Nemerov’s eccentric, impressionistic and strangely hypnotic reconstruction of American life before deforestation and standardisation. Nemerov, a professor at Stanford University, calls it ‘a fable, not a history’.

His theme sounds Whitmanesque – ‘the dense and discontinuous woods of a nation, a forest of people destroying and saving the woods and, in some way, themselves’. But Nemerov uses the snapshot, not Whitman’s scattershot, to assemble a montage of a ‘lost world of intricate relation, of human beings going about their ways, living the dream of themselves in shade and sun’. This is appropriate, since the first American daguerreotype was taken in 1839. Like portrait photographs, The Forest is ‘based on the historical record’ but ‘only some of it is true’.

The first axe falls near the Kennebec river, north of Augusta, Maine. A woodman fells a white pine. The tree crashes in the forest, the lumbermen hear it, they slice it up into 15-foot sections, stamp each section with a company brand and stack them on the ice. When the spring thaw comes, the logs are carried down to Augusta, past the watching Hawthorne and into what Thomas Carlyle called the ‘cash nexus’. It was a world of pine: ‘Floors, shingles, clapboards, pails, packing crates, the cornices and friezes of front doors, the mouldings of fireplaces and the frames of paintings.’ The wooden city of Manhattan burnt down in 1835.

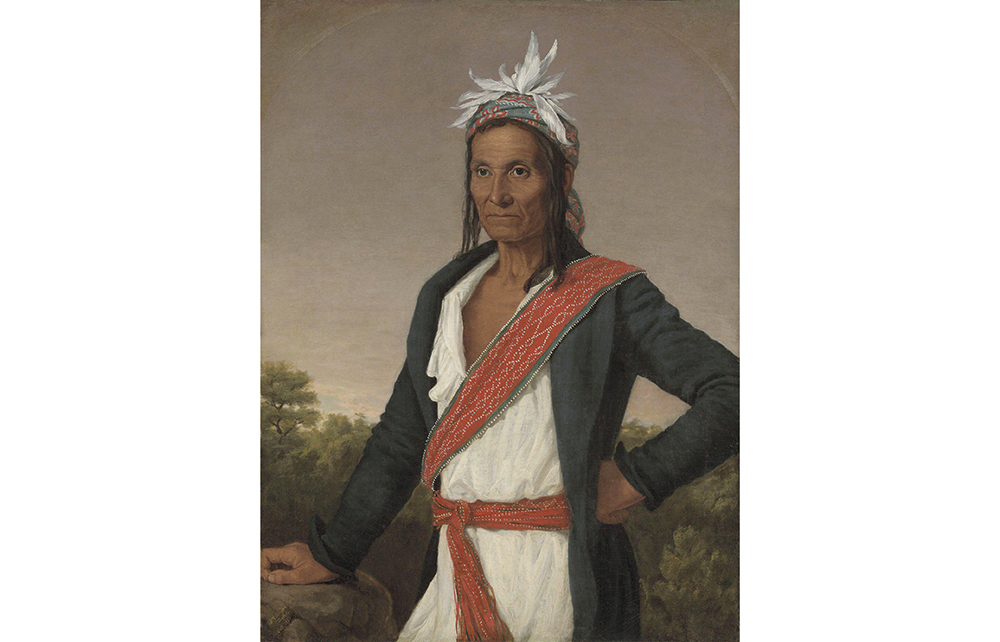

In an ‘artless land’, immigrant improvisers and DIY autobiographers aspired towards nationhood, their creativity driving their age towards its terminus in iron and steel. The painter William John Wilgus, who studied with Samuel Morse before Morse invented his code, portrayed the Onandaga chief Ut-ha-wah in 1838, the year the Onandaga and the other Iroquois tribes signed away their lands in upstate New York to the federal government. While the Iroquois were sent to the Kansas Territory, Wilgus swapped Ut-ha-wah’s portrait for a farm in Lewis County, New York, then flipped it for $1,600 in gold. He died, aged 34, of tuberculosis in 1853. His nephew, the second William John Wilgus, was born in 1865. As a boy, he was fascinated when a surveyor came to map the plot of the family farm. He became an engineer and ‘railroad man’, the architect of the new Grand Central Terminal in New York City, whose two-tier track is still used today. Ut-ha-wah’s echo ‘sped through time and space’ as the train he called the Iroquois.

Claude Lorrain’s campagna is thick with ruined temples and pagan rustics, but the landscapes of Frederick Church and the Hudson River School are epically empty. The New World societies lacked the physical and mythic foundations of the Old: the Native Americans left little trace. In America, Romanticism meant raw naturalism, and what Thoreau called the mulching ‘rottenness of human relations’. Nemerov’s cast of artistic wanderers and eccentrics carve out meaning in a void, like Sam Patch, the famous bridge-jumper, who finally followed his ‘love of nature’ headfirst into Genesee Falls before an audience of 10,000. In America, the ridiculous and the sublime are often one and the same.

If ‘every place has a genius loci’, in America the spirit must be imposed. As the Cherokee were forced on to the Trail of Tears, they marked their passage with a trail of trees. They bent saplings and secured them with ‘a vine, weighted rock or strips of rawhide’. Some of these double-rooted reflexive oaks still stand, ‘a language of trees’ marking where thousands died. The Turkish poet and naturalist Constantine Rafinesque, author of The World; or, Instability (1836), thought he saw Pan in the trees near Lexington, Massachusetts. As the manifest density of American power began to emerge, Alexis de Tocqueville searched out the primeval forest before it was chopped down.

Grouping his biographical images around themes (trees, naturalists, animals, clocks, the supernatural), Nemerov captures the fleeting spirit of a changing place. Readers unfamiliar with the context may struggle to see the wood for the trees, but that is close to how it felt at the time, and perhaps as close as we will ever get.

Comments