One hundred miles or so south of Sydney, lies tranquil Jervis Bay. On its shores, largely reclaimed by the bush, are the abandoned foundations of a large nuclear power station. When it was built in the late 1960s, it was intended to be the first of a network supplying nuclear-generated electricity to the eastern Australian grid. More than fifty years on, this is all that remains of Australia’s only attempt to establish a civil nuclear industry, every attempt since then to revive the possibility stymied by anti-nuclear activists and politicians lacking the courage to challenge them.

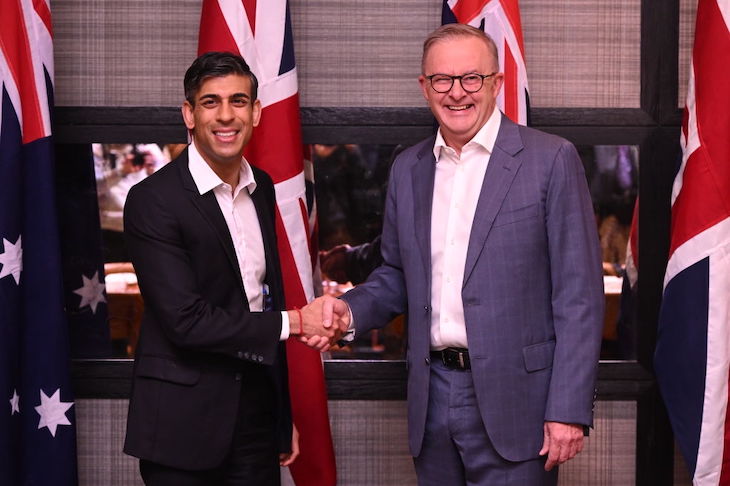

Those doomed foundations symbolise the challenge to Australia to fulfil its central part of the Aukus alliance between her, the United Kingdom, and the United States. In San Diego in the US later today, Australia’s prime minister Anthony Albanese will join Rishi Sunak and US president Joe Biden to announce the central feature of the Aukus pact: the shape of the multi-decade joint plan to build, man and deploy Australia’s own squadron of nuclear-powered submarines.

The plan is two-tiered. First, Australia will acquire and help build up to five American Virginia-class boats, to be followed in later decades by a joint British-Australian Aukus-class boat likely to be a future generation of the Royal Navy’s Astute-class submarines. The expectation, one Albanese is selling aggressively to Australian voters, is that much of the design, construction and assembly will be done in Australia, creating thousands of Australian jobs but carrying a price tag of north of A$200 billion (£110 billion) by 2055. Given inevitable technological evolution, design changes and cost blowouts, the final cost is likely to be much higher still.

Politically-unpopular cuts will need to accommodate the Aukus financial commitment

Aukus conceptually can become the core of an Indo-Pacific Nato. Its geostrategic importance cannot be understated, especially after Chinese leader Xi Jinping earlier today – with the San Diego leaders’ meeting in his sights – told his National People’s Congress that China will ‘build the people’s armed forces into a Great Wall of Steel that effectively safeguards national sovereignty, security, and development interests’. That, in the same speech, Xi again called for ‘reunification’ of Taiwan with China only heightens the urgency of developing Aukus as a strong counterweight to the imperial ambitions of Xi’s communist regime.

The military and industrial capacity of Britain and the United States to fully pull their Aukus weight is undoubted. The British commitment, signifying her return east of Suez after half a century, is especially welcome. Following the 2021 South China Sea cruise of HMS Queen Elizabeth and her task force, it sends a strong message to friends and potential foes alike. The willingness of the Special Relationship powers to work with Australia, and share closely-guarded nuclear submarine and weapons technology, is recognition that Australia – despite her relatively small population and industrial capacity – is crucial to the future stability and security of the Indo-Pacific region.

The question, however, is whether Australia can meet the challenge to pull our own weight fully in the triumvirate. As the decaying Jervis Bay foundations symbolise, Australia enters her long-term Aukus commitment from virtually a standing start.

The lack of a civil nuclear industry is a just the first problem to overcome. Apart from a small, ageing, research reactor near Sydney, there is no civil nuclear presence. An existing nuclear industry would have ensured some home-grown capacity to collaborate with the submarine construction programme, and eventually to help service its operation. As it stands, Australia will depend on its British and American partners for just about everything in relation to Aukus nuclear technology.

Then there is Australia’s industrial capacity, especially shipbuilding. While Australia has world-class shipbuilding facilities, especially in Adelaide, those facilities already are heavily stretched; they are busy building Hunter-class (adapted UK Type 26) frigates and offshore patrol vessels for the Royal Australian Navy (RAN), as well as refitting and upgrading existing RAN ships.

This highlights Australia’s extensive and already challenging naval procurement programme, to which the current Labor government and its Liberal predecessor remain committed, over and above its Aukus investment. Meeting all these existing construction and logistic priorities, and then adding on the complexities of state-of-the-art nuclear submarine development, is a tall order.

Manning the nuclear boats is another challenge. Australia’s existing submarine force struggles to maintain sufficient ship’s companies, roughly 40 crew each, for the Collins boats: an Astute submarine requires more than twice that number of crew; a Virginia more than three times. Australia must start recruiting and training immediately. Doing so, and indeed keeping hold of these sailors won’t be easy. Even with the glamour and service incentives on offer, the high attrition rate of the Royal Navy’s ‘Perisher’ course for potential submarine commanders is telling about the state of recruitment in the RAN.

Lastly, there’s the economic challenge. A$200 billion (£110 billion) plus is not just a strain on Australia’s defence budget: it needs to be sustained by the entire Australian economy, which in GDP terms is considerably smaller than both the United States and Britain’s. It’s not only hard choices between defence priorities that will need to be made. In a national economy saddled with huge public debt for generations thanks to the Covid pandemic, politically-unpopular cuts across the entire range of government spending will need to accommodate the Aukus financial commitment.

Yet that is a burden that most Australians have welcomed, and is embraced by both sides of Australian politics. Australia’s spirit is willing – after all, Aukus was an Australian proposal – but the logistical and economic challenges of making it succeed are great for a middle power that is deeply aware of its responsibility to help assure the stability and security of not only its region, but the wider world.

It won’t be easy, but the political will, and public goodwill, are there to ensure that Australia’s partnership in Aukus will not share the same fate of that abandoned nuclear power station on the shores of Jervis Bay. In San Diego today, Australia’s accepts the challenge.

Comments