Nigel Farage was elected as MP for Clacton by a solid margin of 8,405. Four other Reform UK candidates were returned, and the party won 4.1 million votes. This surely was the beginning of a great change, the breaking of the mould of right-wing electoral politics. Farage spoke excitedly of creating a ‘bridgehead in parliament’ and said his party was ‘coming for Labour’ while it let the Conservatives ‘tear themselves apart’. Yet four weeks after the election, has the House of Commons proved disappointing for its new boy?

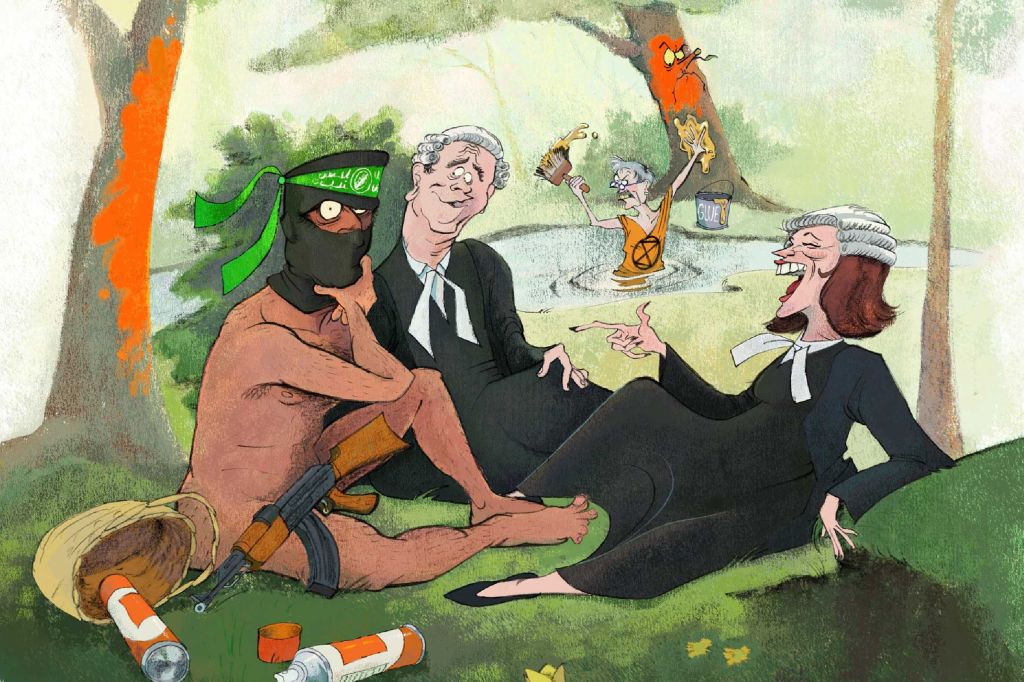

There has been plenty of news for Farage to attach himself to. The Just Stop Oil protests at Heathrow enraged him, leading him to describe the group’s activities as ‘domestic soft terrorism’. There has been serious public disorder in Southend and central London, and of course the tragic stabbings in Southport at the beginning of the week have spiralled into a bitter and violent series of battles between police and right-wing agitators. Farage even found time to vent his fury at the ‘wokeness’ of the Royal Air Force in dropping 14 Squadron’s nickname of ‘The Crusaders’.

Parliament, however, has not given Farage or Reform UK much assistance in their craving for attention. For a while, Jim Allister, MP for North Antrim and leader of Northern Ireland’s Traditional Unionist Voice party, considered formally taking the Reform UK whip in the House of Commons. The additional MP would have unlocked extra public funding for Reform, but in the end Allister decided against the move. Recently, the party’s chief whip, Lee Anderson, complained that Reform UK would not be represented on any of the House of Commons’s select committees, though a party that makes up 0.75 per cent of Members of Parliament would not usually be represented anyway.

Farage himself has hardly thrown himself into his parliamentary duties. He has spoken twice: once on the re-election of Sir Lindsay Hoyle as speaker, when all party leaders were expected to make a contribution, and once in the debate on the King’s Speech, when he spoke for ten minutes. He took part in his first two divisions that same day. Otherwise, he has asked no questions in the chamber, submitted no questions for a written answer, and signed no Early Day Motions. He is not just a fainter voice in parliament than many expected, but barely a voice at all.

The violence in Southport this week showed that Farage’s real instincts are still that of the populist and of a man who prefers an unchallenged, uncritical platform. On Tuesday, Yvette Cooper, the Home Secretary, made a statement to the House on the situation in Southport. Farage’s colleague Lee Anderson made a strangely anodyne contribution, ‘commending’ the Home Secretary and asking her to ‘send our love’ to the grieving families and emergency workers in Southport.

Farage’s approach was different. Forty-five minutes before the home secretary even stood up in the House of Commons, he had posted a video to social media which struck a much darker note. He asked rhetorically ‘whether the truth is being withheld from us’ by the police about the circumstances of the stabbings, and raised the idea that the suspect had been monitored by the security services. The message was clear: this is sinister, it is the tip of an iceberg that involves the forces of the state deceiving the British public, and it all stems from the original sin of mass immigration.

He did not make these arguments in the House of Commons: he does not seem to have been present for the HomeSsecretary’s statement. The reasons are obvious. First, as the leader of a small party, he would have been a bit player in the parliamentary drama, appearing after the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats in the dramatis personae. He would also have been vigorously challenged on his slyly inflammatory arguments. Why would he want to expose himself to that, when he can cut out the middleman and have an uninterrupted monologue on the internet?

Nigel Farage is a showman, a politician with keen instincts for attracting attention but fundamentally dedicated to his own advancement, through the UK Independence party, then the Brexit Party and now Reform UK. The ability to add the letters ‘MP’ to his name will no doubt have been an ego boost, but there are suggestions that being a Member of Parliament does not suit his tactics or even his skill set. This week has been illustrative: while Farage and his party have made the most of the tragic and criminal behaviour in Southport, they have not done so in the House of Commons. Instead the MP for Clacton has found easier, less challenging ways of putting across his views. He might find this parliament a long five years.

Comments