New Year’s Eve was certainly a day for celebration in the household of 53-year-old Jeff Fairburn, chief executive of the housebuilder Persimmon. He was due to receive the first £50 million tranche of shares under a bonus scheme that has won him total entitlements of £110 million. He must have done a terrific job, you’ll be thinking, if shareholders value him so highly. But in fact his winnings (plus £400 million shared by 150 other Persimmon executives) are the freak outcome of a 2012 scheme that was tied to the company’s share price and dividend record but failed to include a cap on how high rewards might go.

Then in April 2013 came George Osborne’s ‘help-to-buy’ initiative, designed to kickstart the housing market by offering homebuyers a government loan of 20 per cent of the purchase price, interest-free for five years. Half of Persimmon’s recent house sales have been underpinned by help-to-buy, and its share price has almost tripled in response. The resulting scale of bonuses is so embarrassing that both chairman Nicholas Wrigley and senior non-executive director Jonathan Davie have resigned; both are ex-bankers, marinated in City megabucks, but with a PR disaster looming they could not persuade Fairburn either to refuse part of the payout or surrender it to charity.

So the story is a gift for the left, whose cheerleaders have been dancing all over it. That being the case, let me attempt a plea in mitigation. Here goes. First, these bonuses are not, as some have suggested, a skimming-off of taxpayer-funded interest subsidies; they are actually being paid for by other shareholders whose holdings have been diluted — but who are still doing very nicely, thank you. Second, to build the number of new homes that might ease the current housing crisis, we need a profitable, fast-expanding private housebuilding sector led by talented and suitably incentivised executives; and Fairburn’s bonanza aside, a scheme that rewards 150 managers is really quite democratic. Third, capitalism never distributes its blessings on a transparently ‘fair’ basis but it is still the best engine of economic progress we’ve got; we should overlook occasional misallocations like this one, and certainly not encourage governments to interfere with them. Have I persuaded you? I’m guessing probably not.

Monstrous stupidity

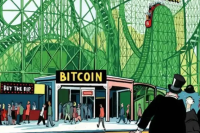

During the long interval since our pre-Christmas issue, Bitcoin has continued to generate crazy headlines — and crazy profits for those smart enough to sell at the peaks. The price tumbled from above $19,000 to below $13,000 but it did not crash out of sight, as sceptics continue to predict.

Meanwhile, from Japan we hear that the ‘wealth effect’ of a million Bitcoin holders who believe themselves richer could be the turbo-boost to consumer spending that Japan’s flaccid economy has been seeking for decades. US news sources express concern about the environmental impact of global computer operations related to Bitcoin, which now consume as much electricity as three million American households or the whole of Denmark. And in London we learn that the Bank of England could ‘trigger the death of high-street banks’ by creating its own Bitcoin-style cryptocurrency next year.

Blimey, you’re thinking, this thing’s a monster. And so it may be, but common to all these stories is a whiff that their reporters don’t really understand what they’re writing about. I can say this because after four decades in the financial world, I admit I don’t fully grasp the Bitcoin phenomenon myself — and after a quarter-century in journalism, I think I can spot a bluffing hack.

But at least that Bank of England titbit is less sinister than it sounds. The Bank has for some time been looking into blockchain or ‘distributed ledger’ technology — a kind of giant virtual spreadsheet that facilitates cryptocurrency dealings — as a possible alternative low-cost payment network to compete with traditional interbank transfers. Such a useful outcome might be the real-world legacy of today’s Bitcoin fever, in which no one knows anything except the gradient of the price graph.

Jamie Dimon, America’s top banker as chairman of JPMorgan Chase, famously said in October ‘God bless blockchain’ but ‘if you’re stupid enough to buy Bitcoin’ you’ll eventually get stung, not least because ‘one day, governments are going to crush it’. After he said that, mind you, a JPMorgan analyst said ‘Bitcoin is the new gold’ and Dimon’s own daughter declared herself a Bitcoin buyer. That’s the way of the world, and there’s a prize for the reader who sends (to martin@spectator.co.uk) the most articulate 100-word justification for following the daughter’s example over the father’s advice.

A loss to scholarship

We should treasure historians whose studies are devoted to warning us against repeating past mistakes. That is particularly so in the financial field, where scholars — few in number and far less famous than their colleagues who write about monarchs and battles — are condemned to watch unlettered moneymen drive markets through the same boom-bust cycle every 20 years or so.

One who strove against that trend was Professor Richard Roberts of Kings College London. Dick to his friends, his oeuvre included Did Anyone Learn Anything from the Equitable Life? and When Britain Went Bust: the 1976 IMF crisis, as well as the prize-winner that fellow historians cite as a masterpiece of original research: Saving the City: the great financial crisis of 1914.

When not burrowing in City archives, Dick Roberts was a convivial Yorkshire neighbour as well as a source of wise advice for my own writing projects. So I was pleased to be invited for drinks before Christmas, but when I arrived the house seemed strangely unfestive. A family member came to the door to tell me that Dick had died of a heart attack, aged 67, a few days earlier. He is a mighty loss to the world of financial scholarship, but I hope his work will be read again and again.

Comments