Philip Womack has narrated this article for you to listen to.

The Shakespeare scholar Sir Jonathan Bate recently claimed that students are struggling to read long books. Depressingly, he’s right. I could have told him the same thing five years ago, when I was teaching at a well-respected Russell Group university. The problem isn’t that students won’t read Moby-Dick in five days. It’s that even if you give them what they want, they’ll still find fault. This all points to a tussle at the heart of modern education: do you cave in to the blighters, or not?

To my surprise, when convening a BA course on children’s literature, I discovered that some of my students balked at reading children’s books. The course looked at the whole caboodle from the Romantics to the present day. It wasn’t a doss: the reading included knotty stuff like Rousseau, as well as all the primary texts. Most students seemed to enjoy it. Why wouldn’t they? Aslan and Bilbo Baggins! It was also intellectually stimulating, with literary, politico-ideological and biographical elements to absorb.

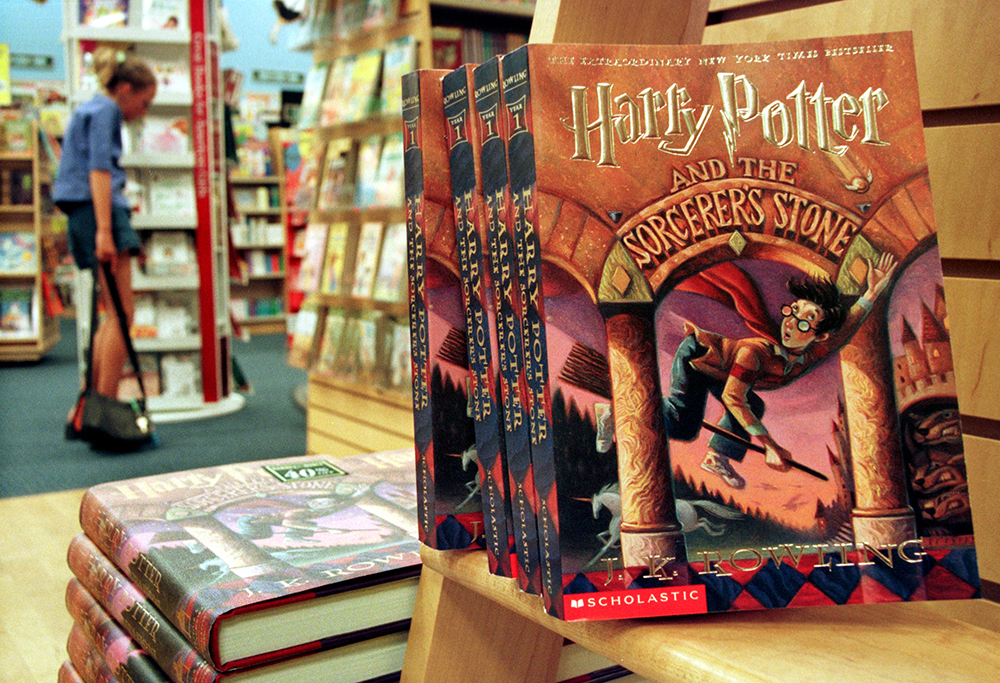

One day, after giving a lecture on J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books, I waited for questions. Several hands shot up. ‘Do we have to read all the books?’ came the first inquiry. ‘Yes,’ I laughed. ‘All seven?’ was the plaintive response. I answered, firmly, that it was Potter week, they’d had the reading list since June, and if they wanted to write their final essays on Potter, they’d have to refer to all seven: we’d been discussing the series as a Bildungsroman.

Later, an email pinged in. There had been complaints. Four, to be precise, from students who thought I had unfairly dismissed their concerns. I was yanked in for a meeting with a couple of departmental bigwigs.

I defended myself. I had devoted months to preparing this course. Surely it was not beyond the capabilities of the average student to read the Harry Potter books, especially when most would already be au fait with Hogwarts? I mentioned that when the seventh and final book was published (607 pages), critics read it overnight. Above all, not to read the set texts was a discourtesy. ‘Who could argue with any of that?’ I wondered afterwards. Well, I was wrong. The students were given a free pass, and yah boo sucks to my lectures. Bildungswhat? Even after that, many students’ final essays only referred to the films, as if I wouldn’t be able to tell the difference. It was all quite deflating.

Many educators nowadays suggest a balance between what students want and what academics want to give them. There is a Goldilocks zone, where lecturer and student meet. This is fine up to a point. There is also the question of ‘relatability’. Why should the modern youth pore over weird sailors chasing whales, when they can delight in Cat Person by Kristen Roupenian?

It shouldn’t need to be stated that feeling uncomfortable is an element of the pursuit of knowledge. There are utilitarian benefits also: gaining the ability to grind through something apparently tedious sets you in excellent stead for life. I’m not sure about the debilitating effects of TikTok et al on concentration spans, but what I am sure about is that if you surrender to the students who complain, they’ll only make more demands. Seven books of Harry Potter too much? How about three? One? A page? A summary?

In the end, if students complain when things don’t go their way, they are not entirely to blame – they don’t yet know what they want. It’s mainly the fault of decades of educational theory, and of a university culture that’s forgotten what it’s supposed to do. The educational establishment must address the fact that learning things properly is not always a teddy bears’ picnic. And it needs to acknowledge that always caving in to students’ whims isn’t right.

Reading that doesn’t immediately spark joy is the best kind. Because at some point it might spark something else, and the world will light up in ways you’d never imagined. As a whole culture, we need to remember to stand firm. If students are required to read what’s on the list, even if they find it a chore, they’ll appreciate it. Many people, years after graduation, regret not taking full advantage of the learning on offer. I’ve never heard anyone say: ‘I’m glad they didn’t stretch me.’

Listen to Philip Womack on The Edition podcast:

Comments