On Monday night Tories gathered on the Terrace Pavilion at parliament for the 1922 Committee’s spring reception, to which every backbencher was invited. The crowd was small, largely made up of Rishi Sunak loyalists eating steak and chips and drinking sparkling wine. The Prime Minister chose not to give opening remarks and instead chatted to the MPs. According to one attendee, the atmosphere was jovial. But no one dared bring up the elephant in the room: Lee Anderson’s defection.

Just hours earlier, the former deputy Tory party chairman held a press conference to announce he was defecting to the Reform party. Even before he started to speak, his former Tory colleagues took pre-emptive steps for his departure by removing him from their various WhatsApp groups. Normally these groups are full of chatter about the smallest developments. This time, they were silent. ‘No one responded for several hours – which is a sign that no one knew what to say – which is rare for us,’ says an MP.

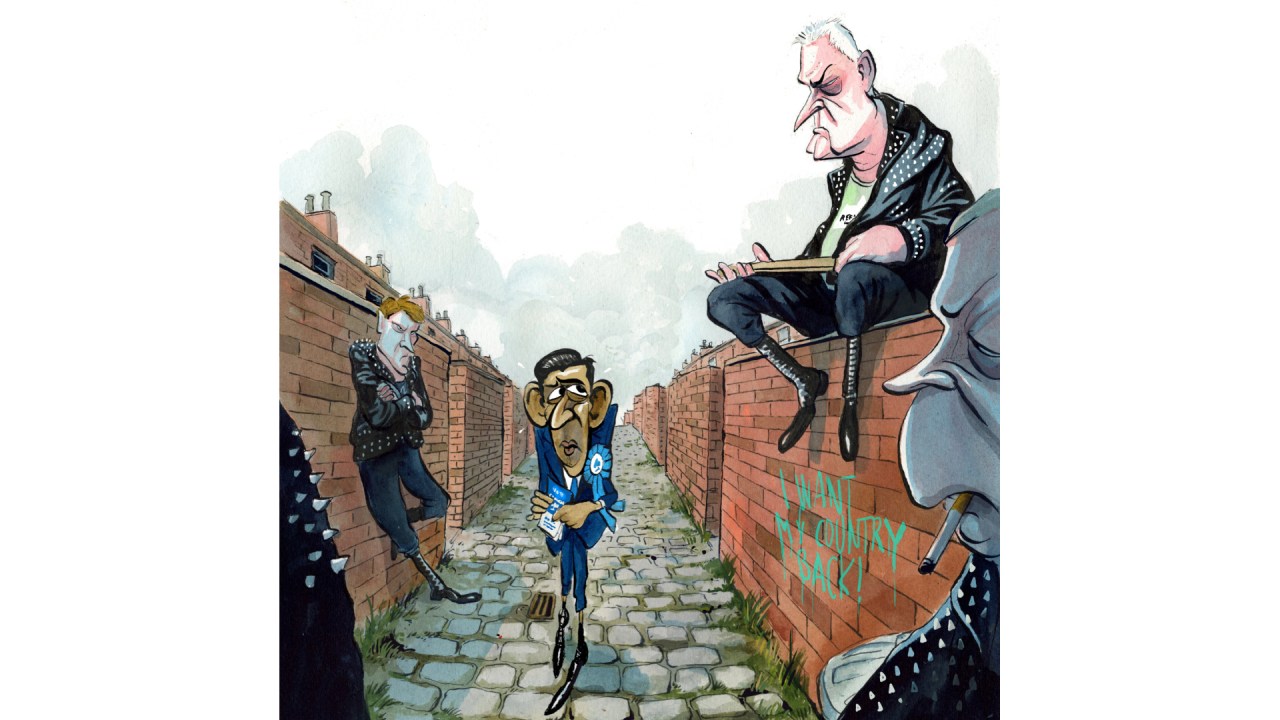

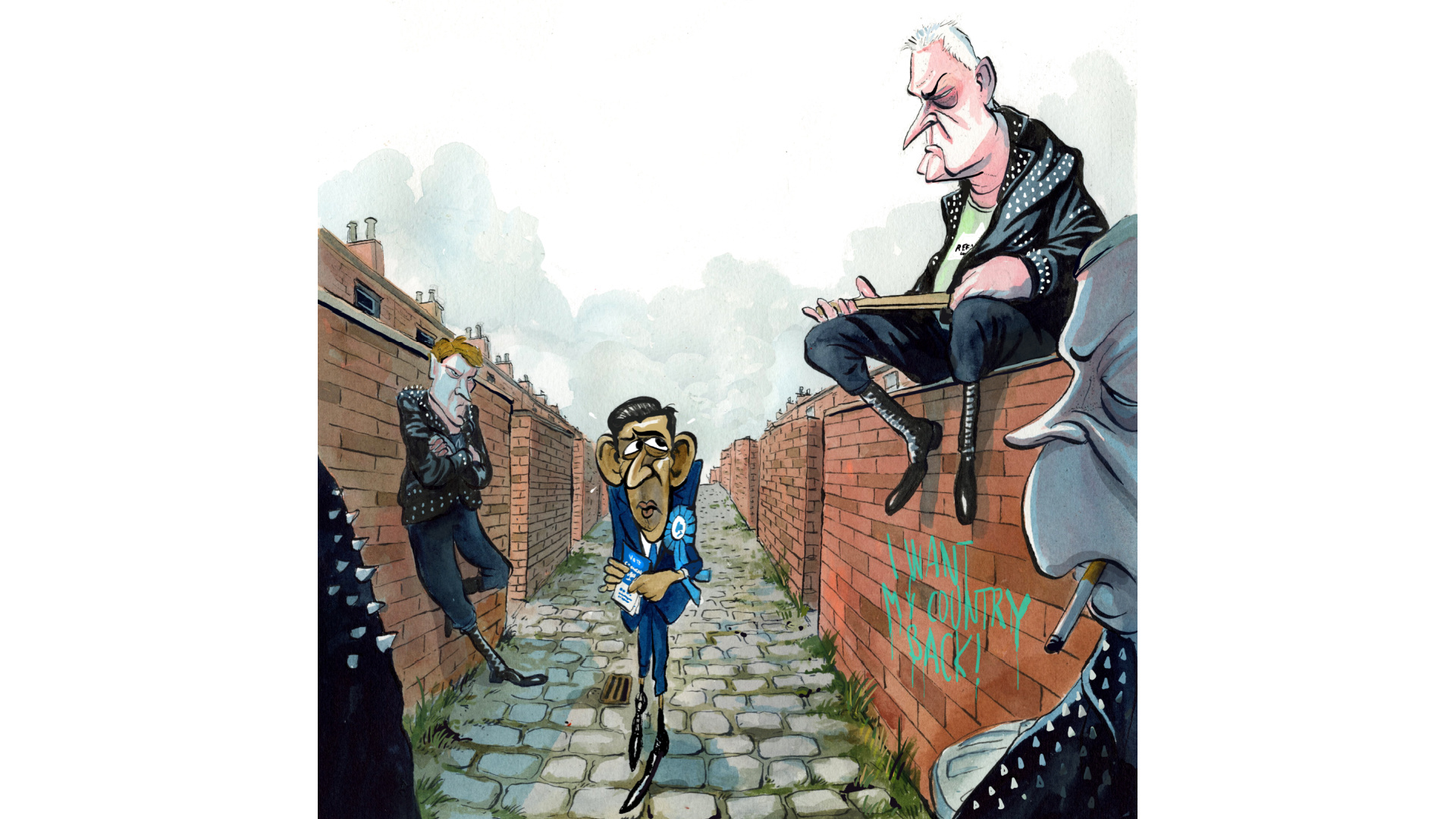

Anderson’s defection was predictable. He had already switched from Labour to the Tories and was top of the ‘Reform watch’ list of Tory MPs at risk of losing their seats and considered likely to defect before they do so. Senior figures in Reform have been wooing Anderson since last year. The first approach was made in Westminster’s Red Lion pub, where it was suggested to Anderson that he would be more comfortable in their gang than with the effete metropolitan tribe the Tories had become under Sunak. No. 10 elevated Anderson to deputy party chairman to show that the Red Wall northerners and the Blue Wall southerners were both key to the new Tory electoral coalition.

But the 2019 coalition, forged by the promise to ‘get Brexit done’, has been buckling ever since the general election. The two groups are divided by their positions on immigration, tax-and-spend and Brexit. The fact that there have been three prime ministers in one parliament is evidence that the Tories can’t decide if they wish to pose as against-the-grain insurgents (Boris Johnson, Liz Truss) or as the party of competence and delivery (Sunak).

Michael Gove, the Levelling Up Secretary, made the case for a bit of each approach at a meeting of the Conservative Philosophy Group on Tuesday night. The speakers that evening were Robert Buckland, Danny Kruger and Lord Frost. These three men are not rivals, Gove said, but can be seen as three flavours of conservative ice cream. As with all ice cream, he continued, the best thing to do is to combine the flavours.

Sunak tried to unite the different Tory tribes when he took office, but in the end it proved impossible. Anderson’s shoot-from-the-hip style led him to accuse Sadiq Khan of being ‘mates’ with Islamists. His suspension from the Tory party, not so long after Suella Braverman was sacked, also after a row over London protests, signalled the end of the 2019 coalition and a split in the right.

Sunak tried to unite the different Tory tribes when he took office but in the end it proved impossible

The Tories are now polling below 25 per cent. Reform is approaching 15 per cent. Tory optimists see a right-wing block of votes which may come together at the last moment, as happened in 2019. But Johnson had Brexit as a cause to unite voters and he was given a boost by the Brexit party’s decision not to field any candidates in seats the Conservatives were defending. The Tories can expect no such pact with Reform. And it is hard for the Tories to write off Anderson, now Reform’s first MP, as a crank when he was the Conservative deputy party chairman for a year.

‘The whole episode has been a massive disaster starting at appointing him as deputy chairman in the first place,’ says a Tory MP. ‘It highlights how we don’t have a strategy for the election. Is it “keep the Red Wall”, “keep the Blue Wall” or try to do both?’ Reform has named Anderson as its new ‘Red Wall champion’. There are certainly plenty of votes up for grabs: polls suggest that the Tories will lose every single one of the Red Wall seats that they gained in 2019.

Reform is also widening its attack. Anderson doubled down on his Islamist comments, declaring he wants ‘his country back’. In the same press conference, Richard Tice, the leader of Reform, also spoke about the cost-of-living crisis, emphasising that Reform is a party of economic as well as social protest. Its ‘contract with you’ reads like a charge sheet against the Conservatives rather than an argument for Reform: ‘Britain has a housing crisis. Record NHS waiting lists. A benefits crisis. Record crime. Net zero is making us poorer and colder.’

‘We have left a fair bit of ideological space for Reform,’ admits a minister. ‘Lots of my constituents would be open to voting for a party that is against the main parties and offering a viable change.’ Or as a Reform figure puts it: ‘Lee’s defection is more visceral than just political calculation. What changed it was his parents saying they could not vote for him if he stayed a Tory.’

For years, the Conservatives occupied most of the space on the right, so frustrated voters never had a coherent alternative party. Ukip was a one-issue party, as was James Goldsmith’s Referendum Party. There have been attempts to revive the Social Democratic Party, but it has never got off the ground. Reform, once it had changed its name from ‘Brexit party’ and Farage stood down as leader, seemed too bland to be effective. Tice, who looks more like a party finance chief than a leader, doesn’t attempt to fit the mould of a populist politician. Reform polls well ahead of by-elections but Tice’s record in actually winning votes has so far been one of failure.

In the Rochdale by-election, the Reform candidate, a former Labour MP, only just kept his deposit. Compare that with the neighbouring constituency of Heywood and Middleton in 2014 when Ukip won almost 40 per cent of the vote. The hope in Reform now is that Anderson attracts so much publicity from the right and the left that he will bring the party name recognition and electoral cut-through. Farage told Anderson on the day of his defection that he had no idea how famous he was about to become.

But Reform does not yet have local power bases. Having a low vote spread evenly is a recipe for defeat. Say, for example, that at the general election Reform wins 10 per cent of votes and the Lib Dems 9 per cent. According to Electoral Calculus, that means the Lib Dems win 40 seats and Reform gets none. ‘Vote Reform, get reform,’ says Tice. The Tories’ response is to say: vote Reform and give Keir Starmer the biggest majority in British peacetime history. ‘That’s the real message we should be giving in the election,’ says one minister. ‘We’re toast anyway, so vote Tory if you want Labour for five years rather than 20.’

Reform wants to seize this moment of peak Tory unpopularity and use it for a realignment of politics

Reform is also thinking long-term. The party wants to seize this moment of peak Tory unpopularity (few prime ministers have seen approval ratings as low as Sunak has now) and use it for a realignment of politics. Its real focus is the election after the next one, when it hopes a shake-up of the two-party system could take place. Just as the SDP-Liberal Alliance split the left in the 1980s, Reform may split the right now.

‘It’s why Nigel is holding fire,’ says a Reform supporter. ‘This time around we need to put down roots – get 15 per cent and keep deposits.’ Then, having overseen a Tory wipe-out, they will bet on Labour failure and fight the 2029 general election on the assumption that voters will be even more annoyed by government failure on immigration, welfare and high tax than they are now.

Much of this is hypothetical. On the day of Anderson’s defection, Tice and others suggested there would be plenty more to come. They claim they are speaking to a dozen MPs, mainly Tory but a few independent and one Labour.

The most likely defection time is after the May local elections. As is becoming party tradition, some Tory rebels are talking about changing leaders at around this time. ‘People are citing the Boris Johnson model. He replaced Theresa May and won an election in six months,’ says an MP.

Johnson is now being touted as the man who could save Sunak, his old nemesis. Some Tory strategists believe he could campaign for the Tories in the north while David Cameron works on Lib Dem target seats in the south. Some Johnson and Sunak allies have poured scorn on the idea but Sunak’s team have been hopeful of a rapprochement for some time. Johnson was being mooted as a guest of honour at last year’s Tory conference, but the peerages row meant it was viewed as a non-starter.

The Anderson defection has had a rare effect of unifying the Tory tribes gearing up for a post-defeat fight. One Nation Conservatives are trying to organise themselves while potential candidates on the right have been meeting with Liz Truss for her benediction. The post-election debate ‘needs to be less about the personalities and instead about ideas’, says a minister, pointing to the work of Neil O’Brien and Miriam Cates. But the debate between the Tory tribes can also be summed up with the question ‘Nigel Farage, in or out?’ On her book tour in the US, Truss said she would welcome Farage to the party, whereas her One Nation colleagues would despise it.

A few months ago, it was possible to find Tory MPs talking about a ‘narrow path’ to victory. Very few do now. Most talk about forms of defeat: ‘All in the valley of death rode the six hundred,’ says one former cabinet member. Normally, Tories have quashed upstarts on the right, such as Ukip, by adopting their cause. This tactic is harder now that the battle on the right may not come down to ideas, but style and method. Voters looking for a more populist front now have a clear alternative.

Watch Nigel Farage discuss 14 years of Tory failure on SpectatorTV

Comments