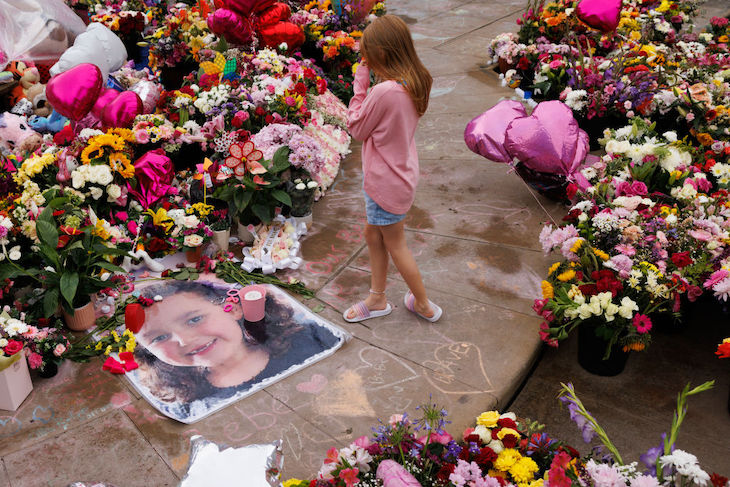

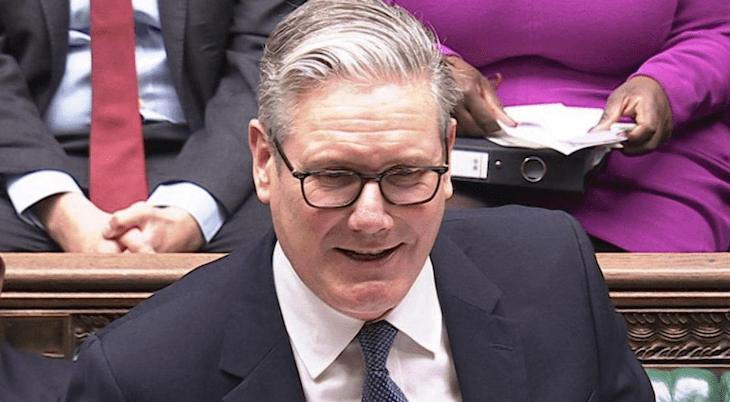

Sir Keir Starmer was explicit in his response to the Southport attack: Britain faces a new terror threat from “loners, misfits (and) young men in their bedroom(s)” radicalised by online violence. There is to be a public inquiry into the state failures that allowed Axel Rudakubana to murder three young girls in Southport in one of the worst attacks on children in UK history. The Prime Minister said the horrific attack last year must be “a line in the sand”. He vowed to change terror laws to deal with lone killers, to ensure that perpetrators like Rudakubana could be charged with terror offences despite having no coherent ideology.

The phenomenon of young men obsessed with extreme violence and determined to act out their fantasies is anything but new

Starmer went on to argue that the nature of terrorism had changed and that the law was not up to speed with what he called a “new threat”. The PM said that, alongside more organised terror attacks, “We also see acts of extreme violence perpetrated by (those) accessing all manner of material online, desperate for notoriety, sometimes inspired by traditional terrorist groups, but fixated on that extreme violence, seemingly for its own sake.”

This is all well and good as an analysis of the problem, but is Starmer correct in suggesting that the Southport killer represents a “new threat”? Hardly. After all, haven’t counter-terror police been warning of precisely this kind of danger – from lone killers radicalised online – for the last decade and more?

Several fatal and attempted attacks have involved young men radicalised online. Ali Harbi Ali, an Islamic State supporter, was given a whole-life sentence for murdering MP Sir David Amess during a constituency surgery in Essex in 2021. Ali stabbed the MP more than 20 times.

Jake Davison, who had a fascination with mass shootings and serial killers, shot five people in Plymouth in August 2021. Paul Dunleavy, a 17-year old from Rugby who offered to build weapons for people online, was jailed for terrorism offences in 2020. Just last week, Callum Parslow, a Nazi-obsessive who had Hitler’s signature tattooed on his arm, was jailed for attempted murder after stabbing an asylum seeker at a hotel in Worcestershire last year.

In other words, the phenomenon of young men obsessed with extreme violence and determined to act out their fantasies, is anything but new. It is somewhat disingenuous of the Prime Minister to suggest otherwise. The bigger issue has always been about how to go about tackling the growing range of challenges faced by the police and counter-terrorism forces.

The Southport murders are merely the latest to throw up the same old questions about why government agencies failed to prevent them from happening. The authorities had contact with the Southport killer, yet between them they failed to identify the danger he posed. How and why did they fail to identify and act on the risk?

More broadly, it is obvious enough that Britain’s terrorism laws require an overhaul to correct some of the constraints that stopped the police declaring the Southport stabbings a terror attack. Officers discovered an academic study of an al-Qaeda training manual on one of Rudakubana’s devices, which included a step-by-step guide to carrying out a terrorist attack. This resulted in him being charged with possessing terrorist material. It did not however warrant the Southport attack being declared a terror incident by Britain’s national counter-terrorism and policing unit. The threshold that must be passed is whether an attack was intended to advance an ideological, political, religious or racial cause. The authorities found no evidence of a motivating ideology and the Southport killer has not said anything publicly. All the police could point to was a teenager obsessed with violence. Changes are long overdue.

The public will judge the government on substance rather than political rhetoric. Starmer’s words about the nature of terrorism changing, with acts of extreme violence perpetrated by loners and misfits, are insufficient. There is little evidence so far that the Prime Minister has devised an actual policy answer to the growing problems.

Comments