If you like a snapshot of a bang-on target, this is it: headline inflation in the euro area for May came in at 1.99 per cent on an annual basis, which gives a whole new meaning to close to, but below 2 per cent. The number itself, however, is entirely meaningless.

As ever, the more important number is the core rate of inflation, which excludes energy, food and alcohol, and which shows no sign of breaking out its range of around 1 per cent. But even the core rate is subject to some noise. For example, the pandemic-related cut in the VAT rate during the second half of last year contributed to the steep fall in the core rate in August and the steep rise in January. But once you cut through these fluctuations, you would end with a relatively stable core inflation rate that stays mostly in the range of 0.8 to 1.2 per cent. Here is the latest update from Eurostat data, with two-digit precision.

| 06/20 | 0.27% | 0.83% |

| 07/20 | 0.39% | 1.18% |

| 08/20 | -0.17% | 0.37% |

| 09/20 | -0.31% | 0.21% |

| 10/20 | -0.28% | 0.23% |

| 11/20 | -0.29% | 0.25% |

| 12/20 | -0.27% | 0.23% |

| 1/21 | 0.91% | 1.41% |

| 2/21 | 0.94% | 1.11% |

| 3/21 | 1.33% | 0.94% |

| 4/21 | 1.62% | 0.74% |

| 5/21 | 1.99% | 0.94% |

But this is only a snapshot of where we were in May. The euro area is clearly behind the US in the recovery cycle, and there are a number of signs of rising price pressures in the pipeline. There are plenty of problems with relying on purchase managers indices, but the latest PMI survey would suggest that there may be inflationary pressures in the pipeline.

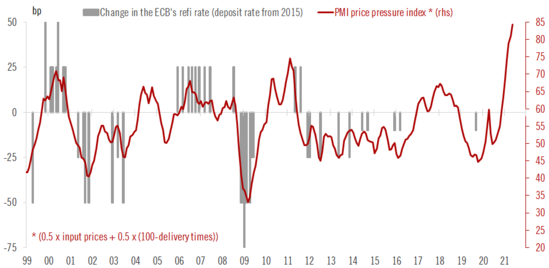

The overall manufacturing index is now at the highest level since 1998, but this is partly a bounce-back. More interesting is this chart on the PMI price pressure index, from Frederik Ducrozet. The definition of price pressure, as outlined at the bottom of the chart, takes into account input prices and delivery times in equal measure. This series, too, registers the highest recorded rate since 1998.

It is this, not the still well-behaving headline rate of inflation that policymakers should look ahead to. In decades of central bank watching, there has rarely been such a calm-before-the-storm situation. The labour market statistics are like the inflation statistics. There are no signs of labour market shortages yet. But there are whispered reports of actual labour market pressure in some critical industries, notably information technology — an important sector in the post-pandemic economy.

This raises two big questions: is the rise in price pressures likely to persist? And if it does, would the European Central Bank counteract it in time? The likely answer to the first question is: some of it will persist, some of it will be temporary.

What about the second question? The ECB has published a working paper according to which the cumulated effect of negative interest rates, forward guidance and QE was +1.1 per cent on GDP growth, -0.75 per cent on inflation and 1.1 per cent on the unemployment rate in 2019. These were heavy policy tools that would all have to be reversed quickly if inflation were to rise. The ECB has all the tools available to fight a rise in inflation. What is not yet known is whether the Bank would actually use them.

This was first published in the EuroIntelligence morning briefing. For a trial subscription click here.

Comments