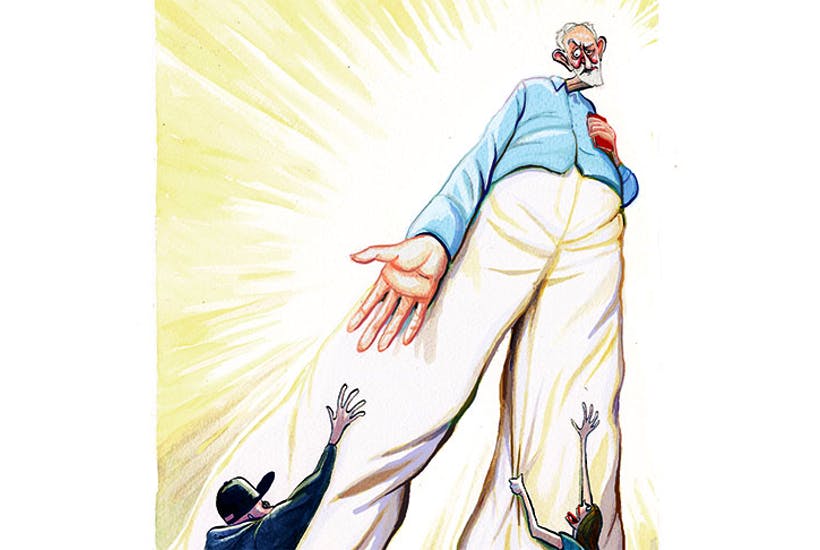

As Labour prepares to say goodbye to Jeremy Corbyn, if not yet ‘Corbynism’, it is possible to put his time as party leader into perspective.

Initially hailed as marking a break with the ‘centrist’ status quo and a response to grass-roots radicalism provoked by austerity, Corbyn’s tenure as Labour leader actually fits a pattern of behaviour observable throughout Labour’s existence. For if the party has changed in numerous ways since it was founded in 1900 one thing remains unaltered: the civil war over what it ultimately stands for. Over decades, members have argued about whether Labour’s objective is to reform society through winning power in Westminster; or socialist transformation through the embrace of extra-parliamentary action. Sometimes it seems as if that war has been finally won – Blair thought so – but that’s just a trick of the eye.

When the party’s Parliamentarians generally held the levers of power, usually thanks to the support of pragmatic trade union leaders, Labour charted the more moderate course. But at moments of electoral crisis – when the prospect of reform through Parliament waned – Labour’s radical voice became louder. After the great defeat of 1931 the Socialist League pulled the leadership to the left and some even tried to create a Popular Front with the Communist Party. When Labour lost power in 1951 activists rallied behind Bevanism and claimed Clement Attlee had been insufficiently radical. This was the same critique that hounded Harold Wilson into opposition after his period as Prime Minister in 1964 to 70. It gathered greater force after the James Callaghan government of 1976 to 79, having struggled to manage the consequences of the international slump, lost to Margaret Thatcher. After that defeat many union leaders joined with activists in believing Tony Benn’s socialist alternative was a better bet than continued moderation and they shifted party policy accordingly.

So while ‘Corbynism’ contained new and disturbing elements, as the Labour leader himself stated in the aftermath of his party’s December defeat: ‘There is no such thing as Corbynism. There is socialism. There is social justice. There are radical manifestos.’ He was essentially right: the roots of Corbyn’s hegemony can be traced to Gordon Brown’s defeat in 2010 and Ed Miliband’s 2015 failure to carve an electorally successful middle way between Blair’s reformism and the more radical demands of members and union leaders.

The main difference between Corbynism and previous radical waves is that he captured the party rather than merely pushing it in a leftward direction while it remained, just about, under the control of moderate parliamentarians. This was largely thanks to 2014 reforms that made it easier and cheaper to join the party. But the reforms also changed how Labour elected its leaders, by abolishing an electoral college in which MPs, trade unions and members held equal sway and creating a one-member-one vote contest. This gives the members – always more radical than MPs – the loudest voice.

After 2015, Labour’s membership rapidly grew as many who had departed during the New Labour years returned. The prospect of electing and then supporting a socialist leader saw membership reach a peak of 550,000, from 200,000 at the time of the 2015 general election. The creation of an empowered membership – as well as the support of key union leaders – enabled Corbyn and his allies to run the party as they liked, especially after the 2017 election. From this unique position of authority Corbyn validated members’ belief in the superiority of the state over the market, reversing the direction of party policy to where it had once stood in the early 1980s. In fact, he went further: the 2019 ‘transformative’ manifesto was the most radical ever presented to the British electorate.

If Corbyn’s influence on the party was profound, his impact on the electorate was less impressive. In 2017 the party advanced significantly from its 30.4 per cent vote share in 2015 to 40 per cent. But this proved a fleeting achievement: two years later Labour’s vote fell back almost to where Miliband had left it, to 32.2 per cent. In effect, Corbyn added about half a million votes to Labour’s 2015 total while making the Parliamentary Labour Party 30 MPs smaller.

Supporters claim that while losing two elections Corbyn ‘won the argument’ by shifting the agenda to the left, forcing the Conservatives to abandon austerity. Yet, even during Miliband’s leadership, there was a strong public appetite for the renationalisation of the utilities, especially rail. Miliband was however too cautious to articulate that demand – Corbyn was not, indeed he went much further. Even so, given his reiteration of the mantra that Labour was ‘for the many, not the few’, Corbyn failed to shift attitudes on inequality and poverty. When elected leader in September 2015, only 15 per cent of Britons thought this the most important issue facing the country. Since then that view has oscillated between 14 and 20 per cent, and on the eve of 2019 election it stood at just 16 per cent. As far as public attitudes are concerned, it is almost as if Corbyn had not happened.

It is too soon to have a complete view of Corbyn’s impact. That depends on what happens next. If Corbynism’s recent hegemony formed yet one more phase in Labour’s unremitting civil war, its future now lies in members’ hands and how they view their party’s fourth defeat in a row. Labour’s history shows that without the prospect of power all radical waves finally crash against the rocks and ebb away with the tide, to disappear for a generation or more. Their fates are sealed once members and those all-important union leaders tire of an impotent ideologically purity. Just as 1950s Bevanism gave way to Wilson’s revisionism and 1980s Bennism was finally supplanted by Blair, if members believe Corbynism now stands in the way of power they will look for more moderate alternatives. It might be hard to believe, but in 1994 58.2 per cent of members voted for Blair as leader despite their many misgivings, because they believed he had what it took to defeat the Conservatives after 15 years of opposition. Labour has now been out of power for a decade, half of that time under Jeremy Corbyn. We will soon know if members think they have spent enough time being what the Labour leader described as the ‘resistance’ to successive Conservative governments – or not.

Steven Fielding is Professor of Political History at the University of Nottingham and is writing ‘The Labour Party: from Callaghan to Corbyn’ for Polity Press, to be published in 2021. On Twitter he is @PolProfSteve.

Comments