Has the NHS turned a corner? The winter crisis may be over, with pressure on the health service beginning to ease, but the pace of improvement is glacial. The latest performance figures for NHS England, published this morning, point to small improvements: waiting lists have flattened off and remain at 7.2 million; 12 hour waits for A&E finally fell; and ambulance response times have improved too.

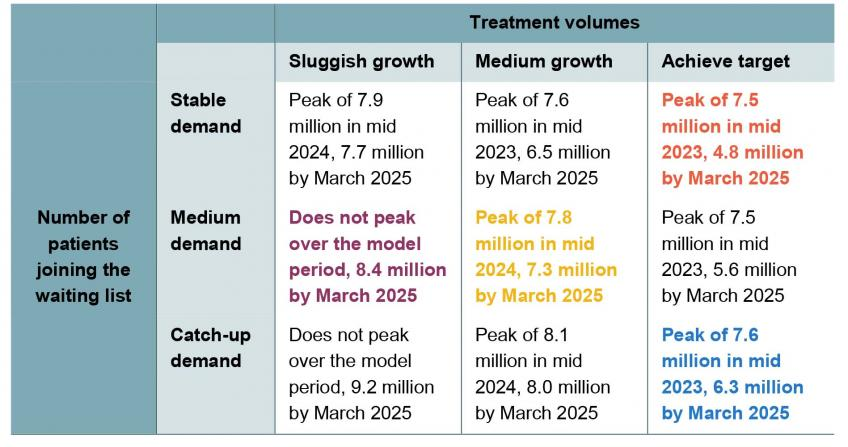

The figures come a day after modelling by the Institute for Fiscal Studies on waiting lists suggested they will at most flatline this year before eventually beginning to fall. Under a worst-case scenario, waiting lists would keep climbing and pass 9.2 million people waiting for treatment in just over two year’s time. If treatment volumes (the number of tests and procedures carried out each month) increase and demand falls, the waiting list may peak by the middle of this year at around the current level.

Here’s everything the monthly NHS figures reveal:

1. Waiting lists grew but only slightly. They’re up back over 7.2 million after having fallen slightly in November. However only 15,000 new waits were added and the line is beginning to flatten off. Under the IFS’s model something drastic would have to change for a significant dent to be made in the lists. As things stand, tests and procedures carried out are barely keeping up with new patients joining the lists every month.

2. But strikes hit procedures. In December 35,000 appointments and treatments had to be rescheduled due to the three days of industrial action. In January another 32,500 were moved or cancelled. The strikes this week then bumped another 41,425 appointments. As a result the number of people treated by the health service fell.

3. Long waits fell slightly. The health service had been making good progress with the people waiting longest for treatment– though things are starting to slow down here as well. The number of people waiting more than a year for treatment has now fallen to 406,000, but that’s still some 236,000 more than the worst-case scenario envisioned by leaked NHS modelling from this time last year.

4. Ambulance response times sped up but are still well off their target. The average wait for a Category 2 ambulance callout – which includes chest pains and strokes – fell to 32 minutes from a horrific 93 minutes seen in December. The target is 18 minutes. The most serious Category 1 calls fell to 8.5 minutes, despite there being a fifth more of these calls than the last pre-pandemic January and more than any other January on records. A reduction in handover delays has helped.

Meanwhile, 111 received nearly three million calls which is the highest in any month since the start of the pandemic.

5. The worst A&E waits finally fell. But last month some 42,735 patients still waited more than 12 hours to be admitted to A&E after a decision was made to admit them. That’s still the third highest figure on record and is only an improvement from the December record high of nearly 55,000.

6. Attendances fell significantly too. The fall in 12-hour waits is explained by the fall in attendances: down to 1.96 million in January from nearly 2.3 million in December. That’s fewer people turning up in emergency departments than the pre-pandemic Januarys of 2019 and 2020 (though higher than last year). So it’s reasonable to ask, why are waits still so long?

Why have the figures started going in the right direction? Last month the NHS announced a plan to scale up emergency services and reduce demand. That is now being rolled out with 10 per cent more beds made available this January than in 2021. But it is surely too soon for these plans to have had any significant effect.

Instead, what the NHS labelled as the ‘twindemic’ of flu and Covid has abated, freeing up more resources. But the state of perpetual crisis continues: norovirus admissions are up 70 per cent in a month and just under 14,000 beds are blocked by people who don’t need to be in hospital every single day. Until that issue is addressed, and treatment volumes are ramped up, it’s hard to see waiting lists ever returning to normal levels.

Comments