Not far into The Life, Old Age, and Death of a Working-Class Woman, Didier Eribon quotes from this balladesque 1980 track by the French singer-songwriter Jean Ferrat:

We have to be reasonable

You can’t go on living like this

Alone if you fell sick

We would be so worried

You’ll see, you’ll be happy there

We’ll sort through your affairs

Find the photos you love

It’s strange that a whole life

Can be held in one hand

With the other residents

You’ll find lots to talk about

There’s a TV in your room

A pretty garden downstairs

With roses that bloom

In December as in June

You’ll see, you’ll be happy there

‘You’ll see, you’ll be happy there’ presents us with an adult gently addressing a parent about the latter’s imminent entry into a nursing home. For all that the speaker seeks to conjure pleasant scenes, and for all that his future tense verbs point confidently to new horizons, one can’t but feel that this move marks the onset of an ending.

The words, put to music by Ferrat, were ‘more or less the same words I said when it was my turn’, Eribon observes ruefully of his mother’s admission to one of France’s 7,500-odd ÉHPADs (or residential facilities for dependent elderly people):

It was as if I was reciting a text I had learned, the lines of a liturgy that so many others had chanted before and that so many others would repeat after me: a prayer book for sons and daughters with a parent whose life will be entirely changed from this decisive moment on.

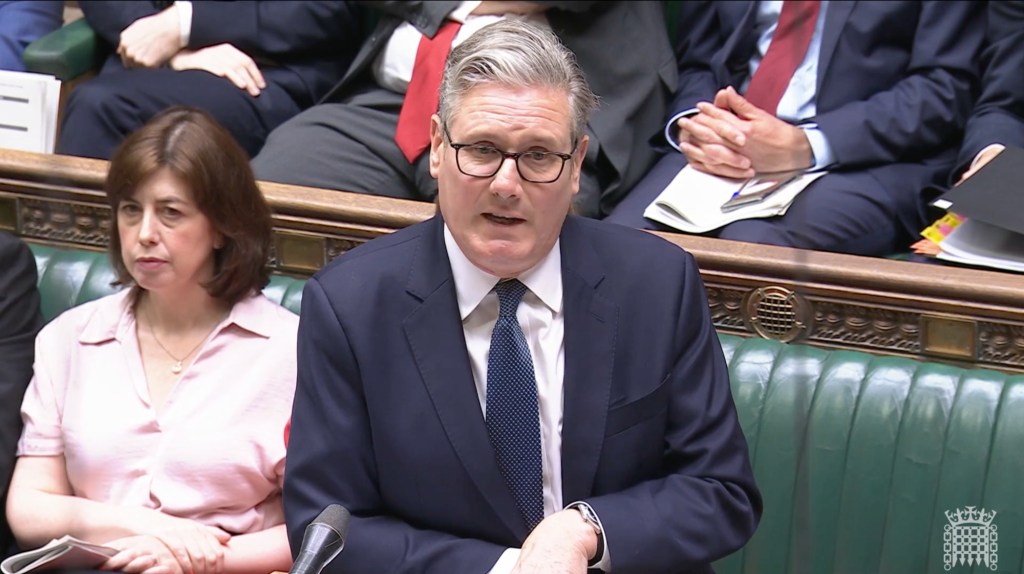

The social scripts that we lean on, depart from and rewrite throughout our lives have long interested Eribon. Now 71 and a professor of sociology at the University of Amiens, he burst to the fore in 1989, after some years as a literary critic, with an acclaimed biography of the philosopher Michel Foucault. Later works theorised homosexuality and how the ‘gay self’ is made, arguing that ‘social verdicts’ mark our identities and shape our trajectories. But in the Anglosphere he is best known for Returning to Reims, a memoir about his vexed relationship with his father and his entry into the Parisian intellectual elite after he spurned his working-class roots.

In his new book, which appeared in French in 2023 as Vie, vieillesse et mort d’une femme du peuple, the focus is on his other parent. She goes unnamed, but her long, hard life in a factory and quite rapid death after moving into the residential home tells us much about the personal and political stakes of care for the elderly, family ties and social systems.

As literature helped the young Eribon come to terms with his sexuality and class transgression, so he turns to other writers in later life to better understand his mother’s situation. The breadth of cultural references – we encounter Foucault, Norbert Elias, Annie Ernaux, Albert Cohen and Simone de Beauvoir via German and Japanese fiction – is stunning, and the readings of them are nuanced. Some passages are overly dense, but Eribon is clearly more comfortable writing at one remove, not least because he dis-agreed with his mother about so much.

His diagnosis of how old age, to nobody’s benefit, is neglected in public discourse is spot on, especially in view of the decades-old debate about a sustainable British social care model. Young people are understandably too busy making a life and enjoying themselves to have the conversation; in middle age we tend not to want to initiate it; and the elderly can’t always take part in it.

Yet Eribon evidently misses his mother – ‘I must now speak of her so that she may live again,’ he asserts loyally – and it is in those more intimate moments that the book’s politics acquire real force. Towards the end, Eribon notes how heated rows between mother and teenage son about his disdain for helping her on badly paid leafleting rounds captured how ‘she was a prisoner for life in a reality no one could wish for, whereas I was dreaming of other things, of leaving, of making an escape’.

The Berkeley professor Michael Lucey, who translated Returning to Reims, has again delivered a stylish version that reflects the spare, analytical bent of Eribon’s prose, although some terms (‘grade school’, for instance) won’t immediately resonate with British readers. Moreover, while ‘working-class woman’ is not a bad approximation of femme du peuple, it lacks some of the phrase’s sociological and philosophical breadth, since it is possible to be both comfortably off and a ‘woman of the people’. In that sense, the title in English could be said unwittingly to impose a ‘verdict’ on the book itself. For this uniquely moving memoir, ‘ordinary woman’ would have worked just fine.

Comments