Chris Ofili

Tate Britain, until 16 May

There’s always something temporary-looking about an installation of Chris Ofili’s early paintings. These works are not hanging on the wall, but lean against it, propped up on feet of elephant dung — the best-known ingredient of this Turner Prize-winning artist’s work. As a consequence, the exhibition looks as if it’s still in the process of being hung, and these elaborately decorated and largely trivial paintings have yet to be hoisted on to the gallery walls. But, no, what you see is what you get: glitter, paint, resin, map pins, collaged magazine images, all dexterously arranged in what the Tate publicity department is pleased to call ‘a distinctive iconography, fusing hip-hop culture, spirituality, folklore and the natural world’.

One of the first works in this retrospective is unambiguously entitled ‘Painting with Shit on it’ (1993). That says it all really, and could readily be adopted as the show’s slogan. Besides Ofili’s excremental obsession there is a fascination for crude pornography, perhaps best instanced by a work called ‘7 Bitches Tossing their Pussies Before the Divine Dung’ (1995). It is a debased and degraded view of life, more occult than celebratory, devoted to the profane with not a hint of the sacred in evidence. Ofili’s rather ordinary ornamental images are jazzed up with elements of hard-core porn and sacrilege in an attempt to relieve the banality.

One of the most hollow and meretricious works here is the portentous temple to the monkey gods called ‘The Upper Room’, a travesty of Christ’s Last Supper, a vast installation in its own wooden construction designed by the architect David Adjaye. I remember seeing it first in the Victoria Miro Gallery, Ofili’s dealer, and wondering at the colossal arrogance of this walk-in monument to pretentiousness. It was subsequently bought by the Tate for £705,000. If I want to think about the monkey god Hanuman, I’d rather read P.L. Travers’s delightful novel Friend Monkey than be subjected to a room of 13 monkey paintings shown in dim reverential light. This is very minor decorative art encouraged to take itself too seriously.

A gallery of works on paper includes a group of pencil drawings of Afro heads which are blatantly retro and 1960s in their patterning. The watercolour nudes are rather tame (Edward Burra made much punchier images more than half a century ago), and the portraits feeble. The pencil nudes, made up of daisy chains of miniature Afros, are another gimmick like the elephant dung, but not without effect. They have a cursive energy that tends to get lost in the overdecorated paintings.

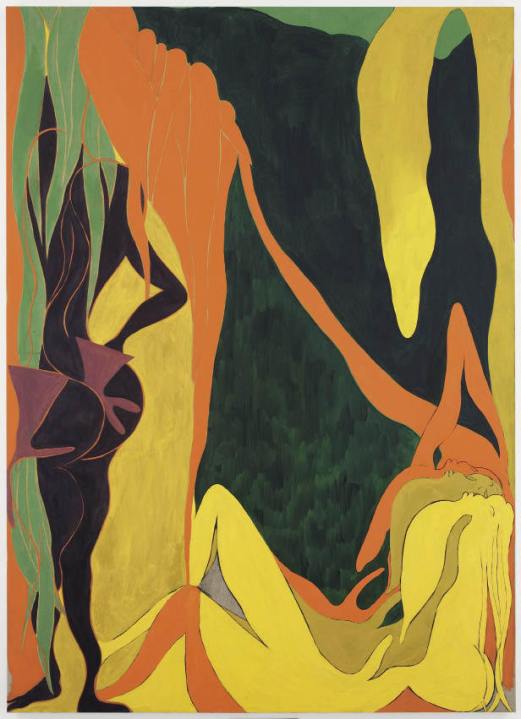

The penultimate room is Ofili’s Blue Period, full of dark indigo paintings difficult to decipher, if the jaded visitor can summon the energy to look at them at all. But in the last room of the exhibition comes an unexpected lifting of the spirits: a degree of legibility and formal invention (wild elongations and wistful mannerisms) coupled with bright, psychedelic colour. The Sixties feeling of the drawings is back with a vengeance, but with a new imaginative drive and richness. The imagery may be a little too reminiscent of Dulac’s illustrations and the wilder extremes of Art Deco but, for the first time in this exhibition, it felt that here was a painter to watch. Seven of the eight large paintings are interesting, and three repay closer attention: ‘Confession (Lady Chancellor)’, with its mauve and orange vibrancy and sea-green mountains, and the drooling, deliquescing forms of ‘The Raising of Lazarus’ and ‘The Healer’.

The new work has been made since Ofili moved to Trinidad in 2005 (the resort of another expat artist, Peter Doig), and is apparently inspired by living on the island. Ofili says: ‘I take a lot of what this place gives for free, which is a very particular mystery which I value and think might have a place in painting now.’ Will there be a new ‘School of Trinidad’, analogous to the St Ives School that dominated mid-20th-century British art? We can only await developments. Meanwhile, I trust this exhibition will encourage people to question the high standing of Chris Ofili (born 1968), former Tate trustee, and make up their own minds as to his achievement.

For anyone interested in a more subtle and unusual (and distinctly beautiful) use of colour, a show of Edwina Leapman’s latest paintings at Annely Juda, 23 Dering Street, W1 (until 27 March) will prove rewarding. Leapman (born 1934) is an abstract painter of great experience and musical sensibility who paints horizontal bands of colour on a differently coloured ground. It sounds simple, but the effects are complex. The lines are not solid stripes but intermittent brush-tracks, full of poignant hesitancies like a radio signal breaking up. The main point of these exquisite paintings is the colour relationship between the layered and modulated ground and the lines which traverse it. All sorts of references are summoned up by these precise yet loosely handled paintings — the movement of the sea, the fall of moonlight, the dapple of shade in a forest. There’s a wonderful serenity here despite the sometimes startling colour combinations: a serenity that vibrates with light and energy.

Advance notices of another kind of exhibition, for lovers of a more traditional approach to landscape. A centenary celebration of the popular Edward Seago (1910–74), presented by the Taylor Gallery, will take place at 28 Cork Street, W1 (15–20 February), paying tribute to Seago’s love for East Anglia and passion for foreign travel. And the Portland Gallery, 8 Bennet Street, SW1, which represents the artist’s estate, will show 119 of his works (11 February to 5 March).

Comments