My most recent constituency polling has found an increase in support for Labour and the Conservatives (and, in their own battlegrounds, the Liberal Democrats) while the UKIP share has drifted down since last year. Even so, neither of the main parties has established a clear overall lead, either in national polling or in the marginals. So while the evidence is that voters may be focusing more on the parties capable of forming a government, they are not finding the choice becoming any easier – or more palatable.

[datawrapper chart=”http://cf.datawrapper.de/PgOJF/3/”]

The latest large-scale national polling I have conducted on the impact of the campaign helps explain why. Over the last month, most party ratings on most attributes have ticked up a couple of points. But the change is not significant and the overall picture remains as it has been throughout the parliament: the Conservatives lead on willingness to take tough decisions for the long term, competence, and (by a much slenderer margin) clarity and reliability.

Labour remain ahead when it comes to values, motivation, standing for fairness and being on the side of ordinary voters.

At the same time, the Tories keep their lead on most economic issues and welfare reform, while Labour are more trusted on public services and the cost of living. The Conservative and Labour campaigns are reinforcing these views, not changing them, or even trying very hard to change them. The Tories want to present the decision as being about competence and leadership, which is why they talk about economic recovery and the difference between Cameron and Miliband; Labour want the election to be about values, which is why they talk about the NHS and non-doms. As my focus groups with undecided voters have shown, little of substance is getting through to most people but what they do hear reinforces what they already think about the parties – good and bad. That is not going to change between now and election day. At this stage, no party is willingly going to switch the conversation to an area where they are vulnerable. They cannot change in four weeks what they have been unable or unwilling to change in five years. In other words, the parties are trapped by their failure to deal with their longstanding problems while they had a chance. Mass defections from the Lib Dems after 2010, plus Labour’s core vote, meant Ed Miliband started with a column of voters adding up to a vote share in the mid-30s. For the Tories to have any chance of winning a majority, they would have to move people from that column into their own. This meant removing the things that had always put them off the Conservatives: primarily, the idea that Tories were not on their side and were not to be trusted with public services like the NHS. The Tories now score no better on these measures than they did at the last election. If too many voters see the Tories as the nasty party, they seem unlikely to win anybody over by ramping up the attacks on Miliband. But if the Tories failed to fix the brand while the sun was shining, Labour have also missed the chance to cement their column and attract new voters in numbers that could have given Miliband an overall majority. In the eyes of many voters who would be quite willing to see the back of the Tories, Labour never seemed to learn the right lessons from what went wrong when they were last in government. People wonder whether an unrepentant party can be trusted with the public finances, and their first question about otherwise attractive Labour proposals is “where’s the money coming from?” The Lib Dems have had to cope with being a party of government elected largely by people who had no such thing in mind. Of those who say they are switching away from the party at this election, nearly half had never voted Lib Dem before 2010. Many of those wanted to vote against Labour without supporting the Tories, or the other way round, or simply could not decide. The Lib Dems needed to show they could make an impact, and are now doing their best to claim the credit for the “nice” things the coalition has done, like raising the income tax threshold. We will see how effective this proves, but meanwhile the party must be wondering whether it was right to have spent so much of its early negotiating capital on the AV referendum and Lords reform. All of this helps to explain why an improving economy – and even improving perceptions of the economy – are not doing more to restore Tory fortunes. In the last two months I have found, for the first time, more people thinkingthan that“the right decisions are being made and things will improve significantly in the next year or two”

Nearly half – many more than are prepared to vote Conservative – accept the argument that further austerity is needed to fix the economy fully.“in a year or two the economy will be no better, or even worse, than it is now”.

A majority say either that they are feeling the benefits of an economic recovery (20%) or that they are not feeling the benefits yet but they expect to (42%). A majority of Labour voters (51%) and nearly half of UKIP supporters (46%) say they are not feeling the benefits and don’t expect to.

But taking the Conservatives’ view on these questions is not in itself enough to guarantee a Tory vote. Conservative defectors to UKIP, for example, are more likely than average to think the economy is improving, that they will benefit personally, and that more austerity is needed (also that Cameron would be a better PM than Miliband and that the Tories have the best approach to most policy issues). But 90% of them say UKIP are “on the side of people like me”, compared to 22% who say it of the Tories, and 88% say UKIP “shares my values”, while only 30% say the Conservatives do so.

A majority say either that they are feeling the benefits of an economic recovery (20%) or that they are not feeling the benefits yet but they expect to (42%). A majority of Labour voters (51%) and nearly half of UKIP supporters (46%) say they are not feeling the benefits and don’t expect to.

But taking the Conservatives’ view on these questions is not in itself enough to guarantee a Tory vote. Conservative defectors to UKIP, for example, are more likely than average to think the economy is improving, that they will benefit personally, and that more austerity is needed (also that Cameron would be a better PM than Miliband and that the Tories have the best approach to most policy issues). But 90% of them say UKIP are “on the side of people like me”, compared to 22% who say it of the Tories, and 88% say UKIP “shares my values”, while only 30% say the Conservatives do so.

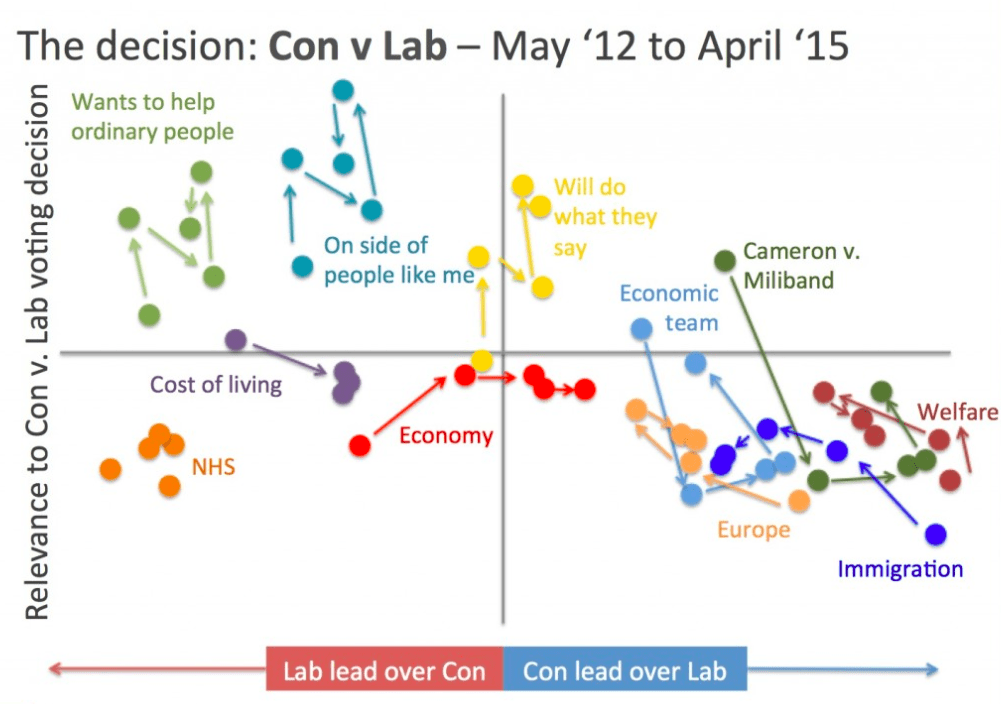

This chart shows the consequences of these factors at a glance. The further a point is to the right, the bigger the Tory lead over Labour; the higher up, the more important it is to people’s choice between the two parties. The Conservatives therefore need as many issues as possible to be in the top right quadrant, Labour in the top left. The arrows show how each issue has moved in five large-scale polls I have conducted since May 2012.

Throughout that time, the factors with the most salience in people’s party preference have been the ones on which Labour have the biggest advantages, while the issues on which the Tories have big leads over Labour have been comparatively less important to people’s voting decisions.

Immigration, Europe and welfare have all fallen in salience in the last couple of months. Preference for Cameron over Miliband and the Conservative economic team over Labour’s has risen further up the agenda as election day approaches, but the Tory lead on both questions is down slightly and both are still of below average importance in the choice between Labour and the Conservatives. For the Tories to capitalise on their advantage on leadership and economic management, they need to show voters why it should matter to them who occupies Numbers 10 and 11 Downing Street.

This is an edited version of Lord Ashcroft’s full analysis which can be found here

Comments