I’ve been interested in informal banking ever since, frustrated in a long Lloyds bank queue in the West End, I persuaded some American tourists queuing with me to exchange their dollars for my pounds at the rate of interest marked on the notice board. No customer is an island, as John Donne did not quite remark.

But today, when it comes to depositing funds and borrowing funds, our financial institutions are acting as though we customers were indeed islands. It’s time we started talking to each other in the queue.

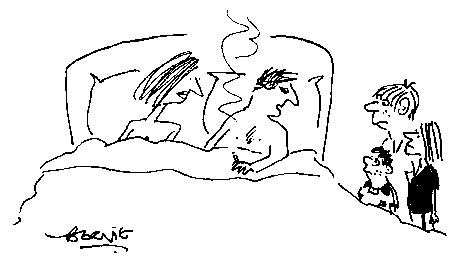

Banks and building societies assume that they alone can make the link between those with money and those in need of money, taking their cut. But if they are too averse to risk, and take too big a cut, they should beware. The customer is capable — if the inducement grows — of learning new habits of unmediated financial intercourse.

The temptations to cut out the middle man have never been stronger. If you were an individual in search of a loan today, and you knew anyone with money who trusted you, why would you go to a bank? And if you were an individual in search of a reasonable return on your savings, and you knew somebody you trusted who needed a loan, why would you go to a bank?

Two preconditions now exist — and look like persisting — for the very considerable expansion of the informal lending-and-borrowing sector of the economy: for borrowers and depositors, that is, willing to bypass the go-between of the banking industry and deal with each other directly. First, those in search of personal or small-business capital are finding it difficult to borrow except at rates of interest wildly in excess of the minimum lending rate set by the Bank of England. Second, those in search of a home for their savings that will even maintain (let alone enhance) their real-terms value are hard-put to find it.

It seems obvious to me that this must soon lead to a weakening of the British habit of mind that assumes these transactions are best done via a bank or building society. With interest rates and inflation where they are, it is now irrational for most people to lend to or borrow from a bank, unless they don’t have any friends. Yet I see remarkably little discussion (at least in the pages of the media that ordinary citizens read) of the important underlying logic implied by three of today’s financial numbers: the rate banks charge to lenders; the rate banks pay to savers; and the rate of inflation.

It is this that tempts me — a stranger to the financial pages — into an area I know little about. Financial boffins will have sensed this already from my clumsy vocabulary; and it’s unlikely I shall finish this column without committing many howlers. Martin vander Weyer has probably already tut-tutted and turned the page. But I take a tilt because whenever I raise this argument with City types, they say things like ‘Hm. Yes. You have a point. It may be happening. I don’t know.’ Then they move on.

Well, is it happening? To some degree, of course, it always has. That families and friends should help each other out with loans is hardly new. Whether or not tax is due on interest received from such lending, I suspect that many people would suppose it wasn’t; and many more would calculate that if it’s informal, nobody will find out: a further inducement to sidestep the banks.

In some communities (the Asian community, for example) I suspect that informal lending is culturally entrenched. Beneath the radar, there’s undoubtedly a degree of informal lending in the family and small-business undergrowth. But how significant is it, and (more important) is it significantly growing? This requires measurements taken over time: measurements I understand we just do not have in Britain. I can only guess that as nature abhors a vacuum, two very present hungers — the hunger for credit and the hunger for a return on savings — cannot be without consequence. Already a website (www.zopa.com) has been established, describing itself as ‘a marketplace where people lend and borrow money to and from each other, sidestepping the banks for a better deal’.

Look at it this way. Inflation is about 3 per cent. Most savings accounts are paying less than 2 per cent. Mortgage interest rates probably average out at around 5 per cent; and some years ago commercial mortgages lost the advantage to borrowers of being tax-deductible.

So if you have (say) £50,000 in a savings account, and a friend or relation you trust who’s looking to buy a house, why not lend that sum to them to help? You’re likely to give your friend a better deal, on less security, yet still get a better return than you would from a savings account.

Or look at it this way. Banks and credit card companies are taking between 12 and 20 per cent interest on overdrafts. So if you have a substantial overdraft that you can afford to service but resent servicing, why not look for someone who knows and trusts you? They could lend you enough to pay it off, and take (say) 6 per cent interest on the loan — less than half what you’re paying a commercial lender, but more than twice what your friend can earn in his savings account.

There is a shaft of irrationality at the core of both the banking and the insurance business. Both trade on a want of trust. Both are in the business of spreading risk.

Insurance relies on its customers’ failure to trust statistical reasoning. In essence, the insurer says to his customers, ‘don’t depend on likelihoods — depend on me, your insurer.’ The insurer then makes his own calculation of the likelihoods. He prices this into the certainty he sells; he spreads the risk; and he takes his cut. But if he demands too big a cut, his customers will turn away, preferring the risk.

Banking relies on its customers’ failure to trust each other. In essence, the banker says to the saver, ‘don’t depend on other men — depend on me, your bank.’ The banker then makes his own calculations of the dependability of mankind. He prices this into the returns he offers; he spreads the risk; and he takes his cut. But if he demands too big a cut, his customers will begin to prefer the risk of depending on another individual.

I suspect that banks and building societies today are demanding too big a cut, expecting that inertia, caution and convenience will continue to deter customers from considering the alternative and choosing risk. They have succeeded in taking governments for a ride. Whether they can continue to take their high-street customers for a ride, I begin to wonder.

Matthew Parris is a columnist for the Times.

Comments