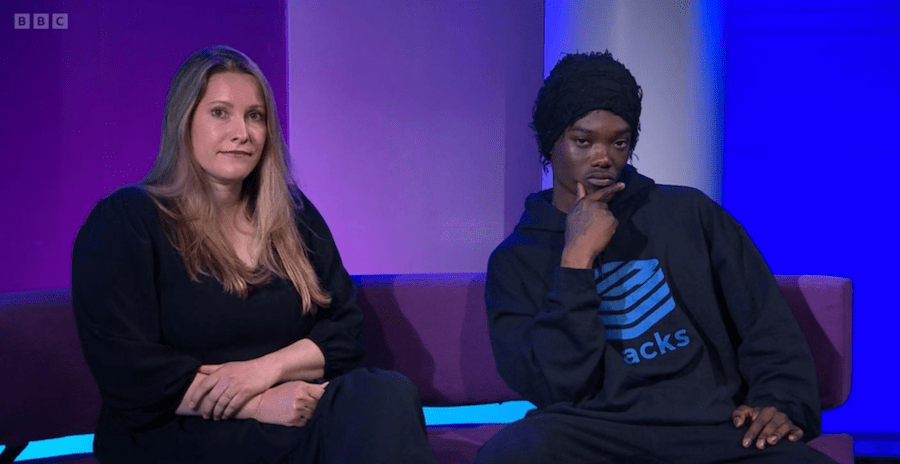

‘Why are you broadcasting what you’re broadcasting? There’s bigger things to worry about.’ In that respect at least, ‘Mizzy’ – the 18 year-old TikTok prankster Bacari-Bronze O’Garro – was doubtless speaking for much of Newsnight’s audience. He had been invited onto the flagship current affairs programme to discuss the BBC’s exclusive interview with the social media figure Andrew Tate, who is facing charges of rape, people trafficking and organised crime. Mizzy, naively captioned by the BBC as a ‘social media influencer’ despite a recent track record of physically threatening members of the public, knew what was happening more clearly than his hosts. ‘I’m on BBC Newsnight now,’ he said. ‘You’re playing the game.’

The other member of the Newsnight panel, the author Laura Bates, asked why the BBC had interviewed Tate in the first place. Sunder Katwala, director of the British Future think tank, raised the same question on Twitter about Mizzy: ‘This character simply would not be on be on any TV news shows except for his undertaking criminal intimidation of women and others, then publicising it online as if a great jape. I don’t think any news channel should reward or incentivise that. The BBC should be the last to do so.’

Newsnight is just one programme, of course. But this edition was transmitted before a tidal wave of coverage for Phillip Schofield speaking to the corporation in a broadcast ‘exclusive’, whose timing was co-ordinated with the Sun newspaper, about his departure from ITV. The BBC’s News at Ten on 1 June included headlines from both the Schofield and the Tate interviews. It fitted into a pattern of intensive BBC coverage of the Schofield case, in which at times the corporation seemed to be losing its marbles. Radio 4’s The World Tonight – known for its weighty coverage of global affairs – made Schofield its lead story earlier this week, in a decision which left former radio executives incredulous. There was also a ‘live’ page on the website charting all the latest developments, and as I write this the most important story in the world according to BBC News is still deemed to be Schofield’s confessional while the second is ‘Alison Hammond breaks down on This Morning over Phillip Schofield interview’. Meanwhile, the Guardian is leading on the deforestation of the Amazon and the Times is majoring on a new fight against cancer.

I have lost count of the number of people around Cambridge and former colleagues across the country who have asked what on earth is going on in Broadcasting House

It may be, of course, that we discover some criminal aspect to Schofield’s behaviour. It is absolutely true that it raises questions about power relationships and unwise sexual behaviour within the media. The story should be reported. But significant figures within the BBC newsroom share the view that the prominence and volume of the coverage are impossible to defend, and one editorial voice goes even further: ‘It seems like the collapse of the news values that we were used to’.

The managers of BBC News would rebut this. These interviews create impact, they drive clicks to the website, they get BBC News talked about. The problem is that this is not necessarily in a good way, and I have lost count of the number of people around Cambridge and former colleagues across the country who have asked what on earth is going on in Broadcasting House. They point to the stories they believe really matter – such as the public inquiry into Covid and the scandal over dodgy PPE – and they don’t believe the BBC is getting its perspectives right. One former senior BBC editor puts it like this: ‘You’ve got a news agenda that is heaving with really important stories about how Britain is governed, but the BBC is aiming for the lowest common denominator and trying badly to compete with the tabloids. That is not their role, especially not the Today programme.’

It is true that the tight licence fee settlement has meant cuts in BBC News which reduce the range of its output – hence fewer stories and more repetition. But it is the selection of those stories and the insistence on dawn-to-dusk coverage which is bothering traditionalist BBC insiders. ‘We are importing our judgement from other news organisations,’ says one, referring to the prominence in BBC News of executives who have previously held powerful positions at ITV, Sky News and GB News. Another veteran of the BBC journalism empire has a pithy view of what’s going wrong: ‘I have nothing to say except that the BBC’s current editor in chief [Tim Davie] is a former marketing executive with Pepsi.’

We must hope that this is a fit of early summer madness. Davie has sensible views on impartiality, but he needs to do urgent work to explain to his managers why distinctiveness is also a key BBC value. It’s the easiest thing in the world to join the media crowd and to delve into what happened in Phillip Schofield’s dressing room, and it is much tougher to shift the agenda and to stick up for what you believe to be important and right. But that has always been my understanding of what the BBC is there for: to be a provider of quality in a way the market can’t. It is a poor outcome when BBC loyalists find themselves fleeing the corporation’s services to find better news elsewhere.

Comments