It was shortly after my fifteenth birthday that I discovered the music of The Beatles. A school friend and I stumbled upon the Fab Four while browsing in a record shop. We were hooked: we’d listen to their songs with almost religious devotion. One thrilling touchpoint for me was their manager, Brian Epstein. As a teenager, discovering we shared a surname – and that he too was a northerner – felt magical. With unreconstructed youthful aplomb I’d boast of the connection. Later, in the world of work, as people forever misspelled my name, I’d summon Brian – note the casual intimacy of first name allegiance – to clarify while enjoying the comforting hint of musical lineage.

Epstein is, after all, a common Ashkenazi Jewish surname, worn lightly by generations of ordinary families

After all, this was the man who, after seeing the foursome play at the Cavern one lunchtime, instantly recognised their star quality. He was instrumental in shaping their clean-cut image, securing their record deal, and managing their affairs during their meteoric rise from 1961 until his death in 1967. Who knows whether, without Brian, that quartet of ingénue musicians would ever have been brought to the world’s attention and given us so much joy. How could any Epstein, fan or otherwise, not thrill to be associated with our namesake?

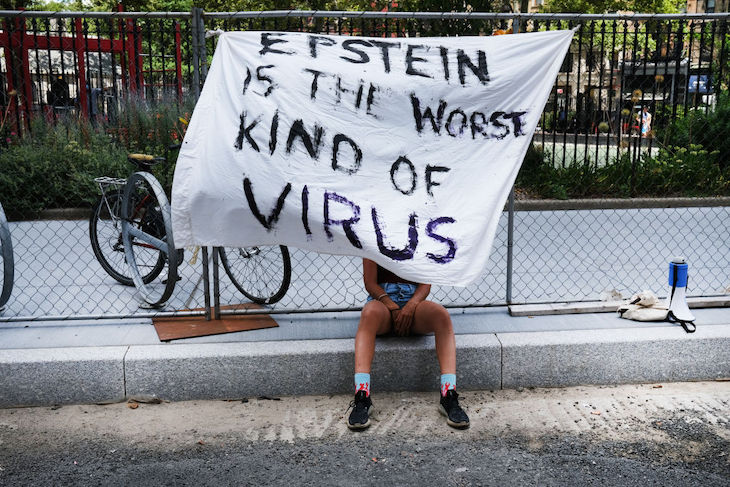

How things have changed. These days, my surname is almost impossible to hear without its far darker associations with the heinous crimes of the late convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein. Now that Donald Trump has approved the release of more files on Epstein, the name will rightfully continue to dominate headlines.

Little wonder that when I introduce myself to strangers – especially news junkies – I sometimes catch a startled expression or a slight wrinkling of the nose. Working as a broadcasting commentator, and sometimes during news reviews, I’ve been called on to discuss the hideous story of the convicted sex offender on air. Inevitably, I’ve had to clarify that I am not that Epstein, even as my own name appears on the screen below me.

Of course, we are not related. We can’t choose who shares our surname. But there is a sadness in knowing that a name I am so proud of has been twisted, in the public imagination, into something synonymous with one of the most notorious criminal cases of the 21st century.

Epstein is, after all, a common Ashkenazi Jewish surname, worn lightly by generations of ordinary families. Rooted in German and Yiddish, it likely derives from the German town of Eppstein – a combination of the Gaulish word apa (‘water’ or ‘river’) and the German stein (‘stone’ or ‘hill’). The name is threaded through stories of diaspora, scholarship, culture and artistic life: Brian, of course, but also Sir Jacob Epstein, the American-born British sculptor and pioneer of modernism, and Michael Epstein, the pathologist who – with virologist Yvonne M. Barr – identified the Epstein-Barr virus.

Even without such illustrious associations, I love the name for its texture and old-world elegance, and the way it nods to my heritage.

What currently saves Brian Epstein from total contamination is the fact that his name was always pronounced – incorrectly but consistently, and not least by his ‘boys’ – as Epst-ine. The criminal Epstein pronounced it correctly: Ep-steen, as those who bear the name do. It’s no compensation to know that, at least, my name is finally pronounced properly.

So how to move forward? The story of this vile sex offender is unlikely to fade any time soon, as scrutiny – rightly – focuses on those who were complicit in his appalling acts and on bringing justice to the victims.

But when your name becomes tainted by such harrowing notoriety – and this is a lament, not request for sympathy – it can feel like a theft, supplanting what has been a vital part of your identity with an unasked-for legacy. What remains is the constant need to distance yourself from an association you didn’t create yet can’t fully escape.

That said, I have no desire to change my surname. The goodness of its associations, I hope, will always outweigh the bad. This, then, is the legacy I choose to embrace: an awareness of an extra layer of responsibility, ensuring that Epstein becomes, in my life at least, a byword for what is just, kind, and decent.

Not so much what’s in a name, but what’s in my name. I hope Brian and Sir Jacob would be proud.

Comments