At the start of this year, Britain looked as if it would be the first major country to vaccinate its way out of lockdown. Kate Bingham and her team had secured Britain a supply of effective jabs delivered at the fastest rate in Europe. This opportunity was then squandered as the government was swayed by advice from Sage advisers, who kept underestimating the vaccines’ effectiveness. Sage produced no fewer than nine scenarios for Covid hospital cases by mid-August, all of which have proved vast overestimates. The government’s reliance on such advice has come at a heavy cost.

In America, where most states lifted lockdown restrictions months before Britain, the economy has recovered to pre-pandemic levels. Britain’s economy has been kept down for far longer, but what we have seen so far suggests there is huge potential for recovery. There are many more job vacancies than before the pandemic. Because of competition, pay is rising — with average earnings up 8.8 per cent over the past year. There are reports of companies fly-posting to recruit workers, and employees quitting their jobs in the belief that they’ll soon find a new one with better pay.

Furlough needs to end before it is allowed to become a permanent part of the benefits system

It’s possible to view this in a less favourable light: to complain about the ‘cost of labour,’ or ‘inflation-busting’ pay rises. Employers have already expressed concern about a Brexit-induced shortage of immigrant workers, as if the government has a duty to supply people willing to do skilled work for unskilled wages. Care homes, for instance, have got away with paying far too little (less than supermarkets do) to employ people whose jobs are hugely important. Another example is the food processing industry, where many companies have neglected to invest in automation because they could find cheap labour so easily.

This is about more than Brexit. The supply of immigrant labour has also slowed due to the pandemic and international lockdowns. When faced with the Covid crisis, many immigrant workers chose to return home, while new, tougher UK border rules prevented more immigrants from arriving. That was a double whammy for companies that depend on their labour.

The low paid are benefiting from these changes. Salaries in construction work, for example, are up 14 per cent year on year. This means longer waits and higher prices for people seeking to extend their houses, but it’s good news for builders enjoying the pay rises. With higher wages comes a greater incentive for businesses to invest in training, better job prospects for workers and an economic recovery whose benefits may be more fairly distributed than the last one. If that pushes consumer prices up a little, it would be a fair trade-off.

The official number of job vacancies now stands at 953,000 — the highest figure ever recorded. Combined with the pay rises, it is a good time for anyone looking for a career change. But this needs to be viewed against the 1.9 million people still on furlough. If their jobs have not yet been restored, there is quite a high chance they will not come back. If so, those still on furlough may be missing the opportunity to retrain.

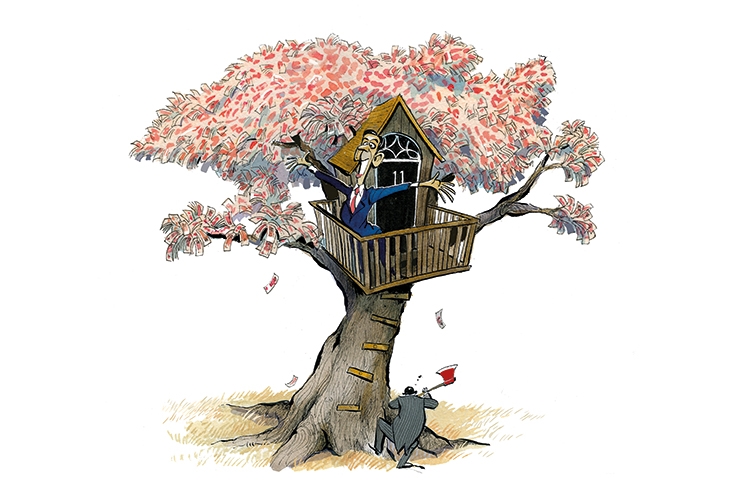

So much of the current worker shortage has been induced by Rishi Sunak. The labour market is being denied potential recruits, partly thanks to a decision to extend furlough far past the period of economic crisis. The pandemic has brought lasting changes to consumer habits and the way businesses operate. The economy is reshaping. A new, leaner, higher-paying economic model may be the result. But the sooner this transition is made, the faster the nation will recover.

The furlough scheme was an appropriate response during lockdown. It came at huge expense (an estimated £66 billion) but it was intended to minimise the immediate economic damage. Many businesses were forced to close at short notice and have since successfully reopened. But furlough needs to end before it is allowed to become a permanent part of the benefits system and ends up, like the old incapacity benefit, causing more harm than good.

That said, the government also needs to be keenly aware of high-skilled labour shortages. It is one thing for factories to be forced to offer higher wages to low-skilled workers; quite another for growing technology–rich businesses to be deprived of the specialists they need to develop new products and services. Britain’s economy depends on air travel to a far greater extent than other European nations, yet the Covid restrictions have badly damaged our international mobility.

Some 93 per cent of British adults have Covid antibodies, which helped to ensure that there were relatively few hospitalisations and deaths in the third wave of the pandemic. The vaccines have done their job. This means we simply do not need to fear the outside world in the same way as New Zealand or Australia. Yet in recent months Britain has deterred foreigners from travelling here, with expensive and quite often pointless tests and quarantine. Now we have left the EU we can come up with a migration regime that helps to protect low-pay work but also opens Britain up to the high skills the economy needs.

Comments