Peter Thiel has been described variously as ‘America’s leading public intellectual’, the ‘architect of Silicon Valley’s contemporary ethos’ or as an ‘incoherent and alarmingly super-nationalistic’ malevolent force. The PayPal and Palantir founder, a prominent early supporter of Donald Trump, is one of the world’s richest and most influential men. Throughout his career, his principal concern has always been the future, so when The Spectator asked to interview him, he wanted to talk to young people. To that effect, three young members of the editorial team were sent to Los Angeles to meet him. What follows is an edited transcript of their conversation.

WILLIAM ATKINSON: Following Zohran Mamdani’s victory in New York, an email that you sent five years ago has gone viral. You argued that with accumulating student debt and housing costs, it was no surprise that young people were turning to socialism. How do you explain that there are Gen Zs, like us, who aren’t on the left?

‘The Trump administration is trying to pull off an extremely difficult thing. America is no longer a great country’

PETER THIEL: My sense is that in the US, Britain, Germany and France, the Gen Z voters are less centrist. I wouldn’t say they’re more drawn to the extremes, but they do not believe there are solutions within the Overton window straitjacket, the narrow space that’s been defined between New Labour and the Tories [in the UK] for the past three decades. And then there’s Reform, a party that repudiates that spectrum. For the first time in 200 years, there’s a real party to the right of the Tories. It’s not just a Gen Z phenomenon, but there’s a Gen Z part that is very important.

WE: You first argued in the late 2000s that the backlash from globalisation would upend politics. Do you often feel that the world is catching up with Peter Thiel?

PT: These things were coming for a long time. Student debt was $300 billion in 2000, around $2 trillion today. The GFC [global financial crisis] in 2008 was a big watershed. Entry-level jobs became less well paid. For students graduating after 2008, it became much, much harder to get out of the debt. Student debt slows you down from buying a house, getting started with forming a family, becoming an actual adult. You end up with a completely different society. It takes a long time to figure this out. But I started talking about this a lot in 2010… Why did house prices go up so much faster than incomes? Not enough was built. A big part was built as a retirement vehicle for older people. They were happy with the prices going up. The Tory party in the UK is probably completely past the point of no return. The suggestion that I have had was that you must start by throwing everybody out of the party who comes from real estate. You must be willing to purge all the people that are part of this dysfunctional system.

JOHN POWER: What would your advice be to someone in their twenties about how they can have an impact in politics? Should they join Reform?

PT: I think about politics a fair bit, but if I spent all my life on it, I would go out of my mind. I would like people to be more involved in right-wing politics, but I’m not sure that’s the best thing for most. You certainly should work for Reform rather than Labour or the Tories. You can criticise Nigel Farage as too much of a Boomer but he’s less structurally hateful to the young people. But maybe this is not the right way to frame the questions. We’re gonna have a revolution from Gen Z – all these crazy things that they are going to be doing. Is this good or bad? I’ve often said, in the early 20th century you think of both communism and fascism as youth movements that went very, very haywire. In the early 21st century, the reality is we have inverted demographic pyramids. There are not enough young people. We’re not going to get youthful communism or youthful fascism. We have this unbelievably oppressive, powerful gerontocracy. Maybe you can get communism or fascism of old people, but it’s very low-energy. It will avoid some of the defects of the early 20th century.But it’ll have many other kinds of problems. The general challenge for Gen Z is that there are big constraints.

My hope is that there always are some technological fixes, defining technology as doing more with less. If the debate is more with more spending or less with less spending, you end up with runaway deficits or extremely cruel rationing. I have critiques of the three biggest European countries – Germany, France and Britain. France is way too socialist. That doesn’t work. Germany is just insane. People have got caught up in crazed ideological fixations. There’s almost nothing like the Green party anywhere outside of Germany. Britain is neither too insane nor too socialist, but it’s extremely unpragmatic. It is extraordinary how lacking in common sense it is. The optimistic case for the UK is that there are extraordinary efficiencies one could wring out of the state. It has the greatest room for improvement of any European country. But why haven’t these things been done in the past 60 or 70 years?… Maybe the entire population is just too docile.

LARA BROWN: You’ve talked before about Europe’s choice between ‘Greta on a bicycle’ environmentalism, Chinese surveillance and radical Islam. Would you say Europe has chosen one path?

PT: The bad doors for Europe, the three doors of the future. For the future to have power as a cultural or political idea, you want it to be different. You can’t stay in this Groundhog Day, this Tory/Labour thing where we’re never doing anything new. The problem is the three actual pictures of the future. Behind door number one is Islamic sharia law. Behind door number two is the totalitarian CCP surveillance state, a hi-tech dystopia. Behind door number three is Greta with a bicycle, and then there’s no fourth door. This is why Greta’s been winning.

JP: A lot of people on the American right talk incessantly about how terrible Britain and Europe are in general. But I think there’s selective blindness and chauvinism from some people on the American right about the condition of their own country. There is nowhere in Europe as bad as Skid Row in Los Angeles. What do you make of that?

PT: I would defend the Trump version of the Republican party vs the zombie Reagan-Bush era. I don’t think President Trump or J.D. Vance are absurdly optimistic or panglossian about things. Make America Great Again was the most pessimistic slogan any president had in a century, and certainly that any Republican president ever had. The Trump administration is trying to pull off an extremely difficult thing, because the red pill is that America is no longer a great country. But you have to make sure it doesn’t become a gateway drug to a black pill, where you become nihilistic and give up and you’re destined to eat too many doughnuts in a trailer park. I don’t think that the right are overly optimistic in America. I don’t think there’s a problem where people describe things as even worse in other places. People in the US don’t pay attention to the world at all. We are a semi-autistic country. Maybe not quite as autistic as China, but we do not think about anything going on outside this country that much.

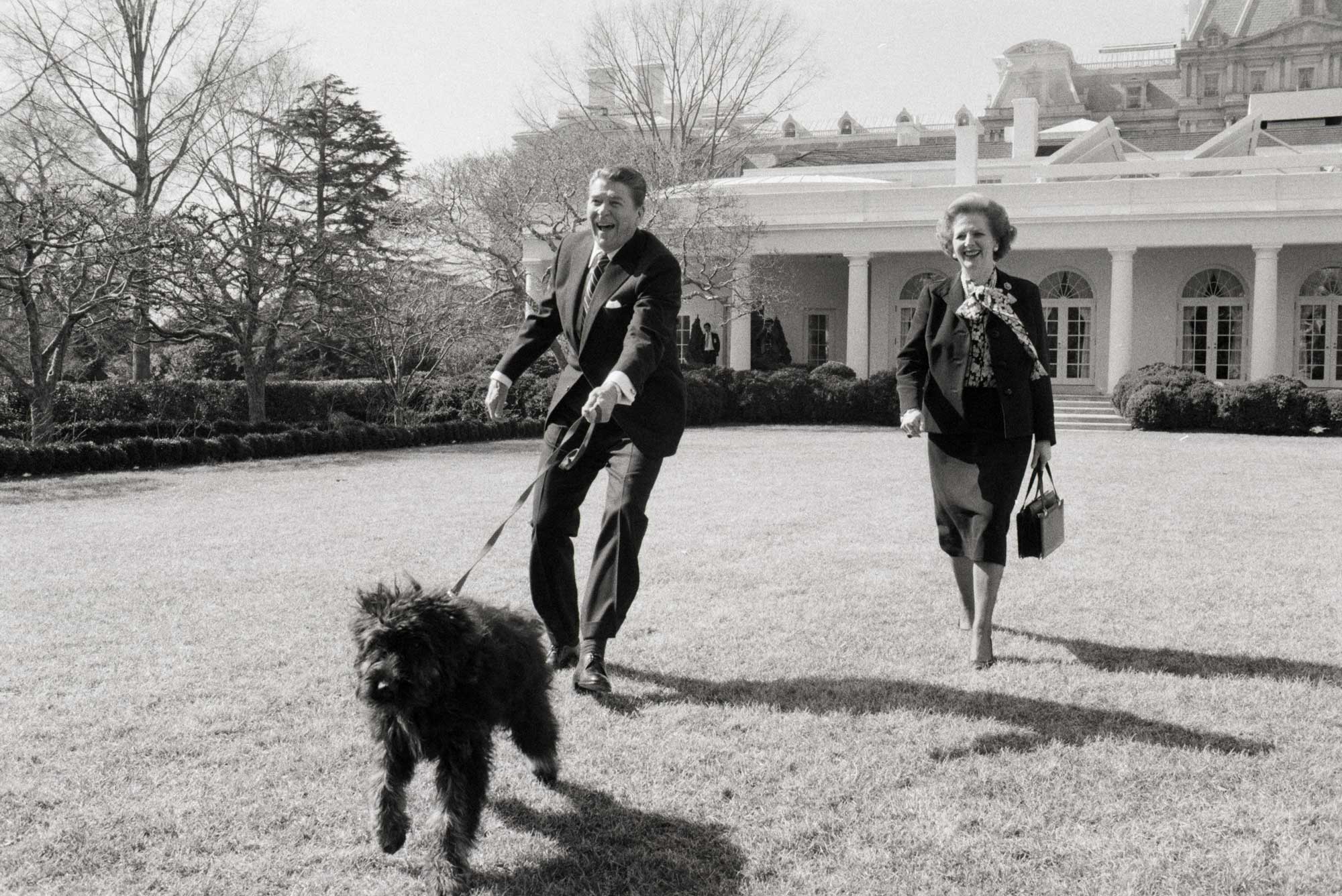

LB: You mentioned the UK has undergone 70 years of stagnation. Many on the British right would agree, but may think that the period from 1979 to 1990 under Margaret Thatcher offered a respite from decline – she pursued unpopular but necessary policies such as anti-inflationary measures despite employment implications and her approach to the Unions. Would you question this narrative?

PT: Reagan was very formative for me. I was in eighth grade in 1980 when Reagan got elected and felt at the time he was an incredibly great president and had solved all these problems once and for all. I think if I lived in the UK under Thatcher, I would have felt similarly. But they weren’t durable. We got Clinton and Blair after. The size of government didn’t shrink that much. The government sectors didn’t get weakened.

‘Capitalism didn’t increase inequality but globalisation did’

There’s been a slowdown in tech since the 1970s. There was progress in the world of computers, internet, mobile, crypto, maybe now AI, but in a lot of other areas there was a much slower kind of progress. The question is, why did we not notice this faster? I think it’s because Reagan and Thatcher created a big lift. They made societies more capitalist by lowering marginal tax rates and deregulating. Lots of people got fired but the economy grew so most people ended up better off.

Reagan and Thatcher were exactly right for their time. But it wouldn’t work for all time. And to the extent that this distracts us from these science and technology questions, then it was somewhat problematic.

Then there was the Clinton-Blair one-time fix, which was that you could somehow grow the economy and increase productivity through globalisation. That also probably gave you a big one-time lift. It came with very big long-term problems. It led to far more inequality. The Gini coefficient in the US went up more under Clinton than any other president post-1945. So capitalism did not increase inequality, but globalisation did.

My telling of the 50-year economic history is that we tried more capitalism with Reagan and Thatcher and it was the right thing to do. More globalism with Clinton and Blair was sort of the right thing to do, though it had more negative externalities that people were very dishonest about. We now need to do something very different.

LB: Helen Andrews recently posited that feminism and gender-balance initiatives in the early Noughties led to a ‘Great Feminisation’. She claims this caused the prioritisation of safety over risk, a workplace culture dominated by consensus and appeals to emotion rather than logic in decision–making. How much do you buy into this as a theory of stagnation?

PT: I think it’s very courageous of her to tackle something that is relatively taboo… Yes, I think there was a shift towards a risk-averse society. Feminisation was part of that. Things also went wrong with educational institutions or too much regulation. The deeper cause is that there was something dangerous and scary about where a lot of science and technology had gone.

By the time you get to Los Alamos and nuclear and thermonuclear weapons, you really wonder whether technology has gone in a very dangerous direction. One cultural history is that there was a delayed response to nuclear weapons. This really kicks in in the 1970s where we are trying to regulate, stop, slow down science. But I would say that feminisation was a part of that. You have these high testosterone men that like to push buttons, or the physicists that like to build bigger bombs. If we replace the eccentric male scientists with less talented DEI people, that sounds like a bug, but maybe it’s a feature. We’re going to end up with this really lame world where nothing happens, but it’s maybe harder for it to blow up. My instinct is to push back against all this.

LB: Are you saying that diversity and inclusion efforts were an attempt to derail technological progress?

PT: I think at some point people got very scared of where this stuff was going. Absolutely. It wasn’t just the nuclear thing. I would say that environmentalism as a movement was very focused on the dangers of limitless progress, even though in theory, you could have a lot of forms of environmentalism that would be pro-tech, right? If you’re concerned about climate change, we could build lots of new nuclear reactors that don’t emit carbon. But if we’re worried that nuclear reactors could be dual use and used to make nuclear weapons then you can’t do that. In some sense the energy shifted into this very anti-tech, anti-science direction for the past 50 years or so.

LB: And you think DEI was a good way to achieve anti-tech goals?

‘We’re going to end up with this really lame world where nothing happens but it’s maybe harder to blow up’

PT: It’s always hard to know how intentional these things were. Diversity can function in an anti-tech way. If diversity really means homogenisation, let’s apply that to scientists. There’s no heterodoxy allowed, no heterodoxy on climate science, no heterodoxy on evolution, no heterodoxy on vaccines, on masks, on the origin of Covid. Everyone looks different but has to think alike. So diversity means conformity. And conformity is not compatible with science. And if diversity is a shibboleth, which I think is its important meaning, then we’re worshipping this god called diversity. It’s an unknown god. It’s a hypnotic magic trick that redirects our attention. And so we don’t care about science any more.

JP: You seem to have a wider picture of American history, particularly in regard to wokeness. Many MAGA-adjacent people seem to think wokeness, or ‘cultural Marxism’, came from nowhere in the early 2010s, while you have identified before that it is a postwar phenomenon.

PT: The culture wars are important. And there are ways in which there’s a side that’s right and there’s a side that’s wrong. But the big problem is that’s distracting us from things like housing or the economy generally, or science and tech or maybe even the CCP takeover of the world. This is where I push back against using the term ‘cultural Marxism’. I always think Marxism was at least about the economy. The focus on identity politics, multiculturalism, affirmative action, starts in the 1970s. That’s when inequality starts to go up. These things were at least correlated with us getting distracted from what I consider to be more important problems.

JP: There are parts of the American right who now look at the changes of the 1960s, such the Civil Rights Act, and think it’s time to re-evaluate the postwar social consensus. What do you make of that?

PT: I don’t think you can ever strictly go back. There are three questions about the history going back to the Helen Andrews piece or my stagnation thesis. First, there’s a question of what happened. Second is a question of why it happened. Then there is a very different question of what should be done now. That’s in some ways very different from the first two. Even if we can agree there’s been stagnation, even if we say the society became too feminised or too risk-averse, we don’t want to just get blackpilled from that. And then the question is: where are the places that you have some agency to get out of this straitjacket?

WA: Are you optimistic that that’s happening? And do you think you’ve contributed towards it?

PT: Somewhat, and very much yes.

LB: Earlier you alluded to three doors we can go through: radical environmentalism, sharia law, or Chinese-style authoritarianism. If none of us wants to go through them then what’s the way out?

PT: It’s a challenge on a political level because when you’re trying to win elections it ends up being about broader narratives. For people in Silicon Valley, in a way it’s more local. You can build a company and solve particular problems in that context. Silicon Valley turned out to be a big place where there was a moderate amount of freedom of action in the past few decades, although it wasn’t a panacea. There’s a part of me that thinks that for some problems you have to go through politics. If we’re going to come up with new cures and new types of nuclear power you have to somewhat deregulate the FDA [Food and Drug Administration] and the NRC [Nuclear Regulatory Commission]. Some of these things are entangled with politics. But a lot of progress has happened that is decoupled from politics. One of the things that’s still healthy about the United States, unlike Britain and France, is that the political capital, the financial capital, the technological capital are all in different places, so it is very decentred. There are places where these things overlap, but there’s some way where people are able to do things that are independent.

JP: Is tech going to come to the rescue like the Eagles [in Lord of the Rings], deus ex machina, providing abundance that can kind of smooth over some of the economic challenges? And as a rejoinder to that, do you think the AI bubble is about to pop?

PT: There are all sorts of things that I don’t particularly like about the AI revolution. It seems to be very concentrated on bigger companies, so it’s possible a lot of the returns are captured by a few companies, possibly leading to very uneven growth. While it may be a complement to human labour, it is probably more of a substitute than a complement. It will have a zero sum feel to a lot of people. At the same time if there is no other vector of growth in our society, we would be out of our minds not to take it. I don’t think it’s big enough to solve the budget deficit, but if the US embraces AI and Europe rejects it, I think the US is in somewhat better shape than Europe is.

‘There are all sorts of things that I don’t particularly like about the AI revolution’

On the question of whether or not it is a bubble, I get asked this a lot by Europeans and that is how you know that they’re not going to build a lot of AI in Europe. If it’s a bubble, then people are spending too much money on AI, and they’re building too many data centres and buying too many chips, and you’re eventually going to get seriously diminishing returns on that. During the 1990s bubble, it was mainly the telecom fibre-optic infrastructure stuff where people really spent way too much and that had to get dialled back. But maybe it’s the other way around where there are high returns to AI, enabling the automation of certain workflows and enhanced productivity.

If the AI bubble does not burst, it’s possible that it ends up being quite inflationary because you have to use more power for these data centres. The atoms part of our economy is regulated and it’s hard to ramp up the power. But if the returns on power going to AI chips are really high, it will absorb a lot of energy. Interest rates could be higher because there’s more demand for capital. My macroeconomic placeholder is that it’s going to keep going.

I’ve been allergic to AI for a long time because it can be a horrible buzzword. There was a 2016 report during the Obama administration on AI by the National Science and Technology council. If you did a search and replace, and replaced every use of the word AI with computers, it would have read the same way.

AI also meant all these really different things over time. In 2014, [Nick] Bostrom defined it as machines being way smarter than humans. Kai-fu Lee wrote the CCP counterpoint AI Superpowers in 2017, where he defined it as this sort of low-tech, big data machine learning. Then in 2022 it turns out the AI revolution is LLMs [large language models] which can pass the Turing test. People had thought this would be what AI was for 70 years. So in the decade before we were about to pass the Turing test we had forgotten about it.

The dynamic when one has to think through a lot more in company formation is not entrepreneurship as a value. In some ways the important thing is building something scalable. This is where technology is really different from science. Big science is an oxymoron. When you scale science to make it into a science factory, there’s no science going on. Big tech is not an oxymoron. It’s extremely powerful, extremely strong – maybe too powerful, too strong. But from the inside, that’s the great sort of business that one wants to build. Noam Chomsky, the communist linguist from MIT, said that in the US, there is basically one party, the business party, that has two factions, called Democrats and Republicans, which are somewhat different but carry out variations on the same policies. The intuition is that maybe all men and women are created equal, but not all businesses are.

If you look at the ratio of how many businesses there are per 100,000 people: what part of the US has the lowest number of businesses? Silicon Valley. That’s because the costs of business are higher, so these subscale businesses that are too small to go anywhere are even harder to get started. In a third-world country where there are no good businesses and everyone is an umbrella salesman, they are very entrepreneurial, but not in a scalable way. So you need to differentiate entrepreneurship from scalable businesses.

‘If you’re too focused on history, you don’t pay enough attention to the future’

There’s this economist called Thomas Gür who has researched the idea that immigrants are more entrepreneurial. While that is correct, you have to adjust for the quality of the businesses and the immigrants start businesses by starting a taco truck because there’s nothing else you can do. It’s better than going on welfare. But that’s what you do when you’re not really part of a society. It’s better than nothing, but what you really want to do is scale.

JP: Is there a cutting-edge domain that you would focus your energies on?

PT: One of the lines we had in Zero to One [Thiel’s 2014 book about startups co-written with Blake Masters] is from Anna Karenina. It’s the opening line: ‘Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.’ The opposite is true of business. All failed businesses are more or less alike because they fail to escape from this problem of homogeneous competition. They didn’t do anything special. All successful businesses are special in their own way. That’s the closest I can give you to a formula and it’s incredibly hard to figure out what that is, or how to do it. I have some feel for it, I know it when I see it.

To wrap things up, I have spent a lot of time thinking about the past. That’s because it’s important. It’s how we got here. It’s what shaped a lot of these debates. At the same time, there’s also some limit to history. If you’re too focused on it, you don’t pay enough attention to the future. The point is not just to reflect on the past.

There was a medieval play on the Antichrist from 1160 or so, Ludus de Antichristo. It’s not a very good literary production, but there are these three kings, the Antichrist conquerors who focus on things like nationalism or their countries or their history. They lose because they’re too fixated on the past whilst the Antichrist is thinking about the future, and about what can be done. They don’t see Antichrist coming. So while it’s very important for those on the right to think about the past, to think about the history and what happened – they still should not lose sight of the future.

Comments