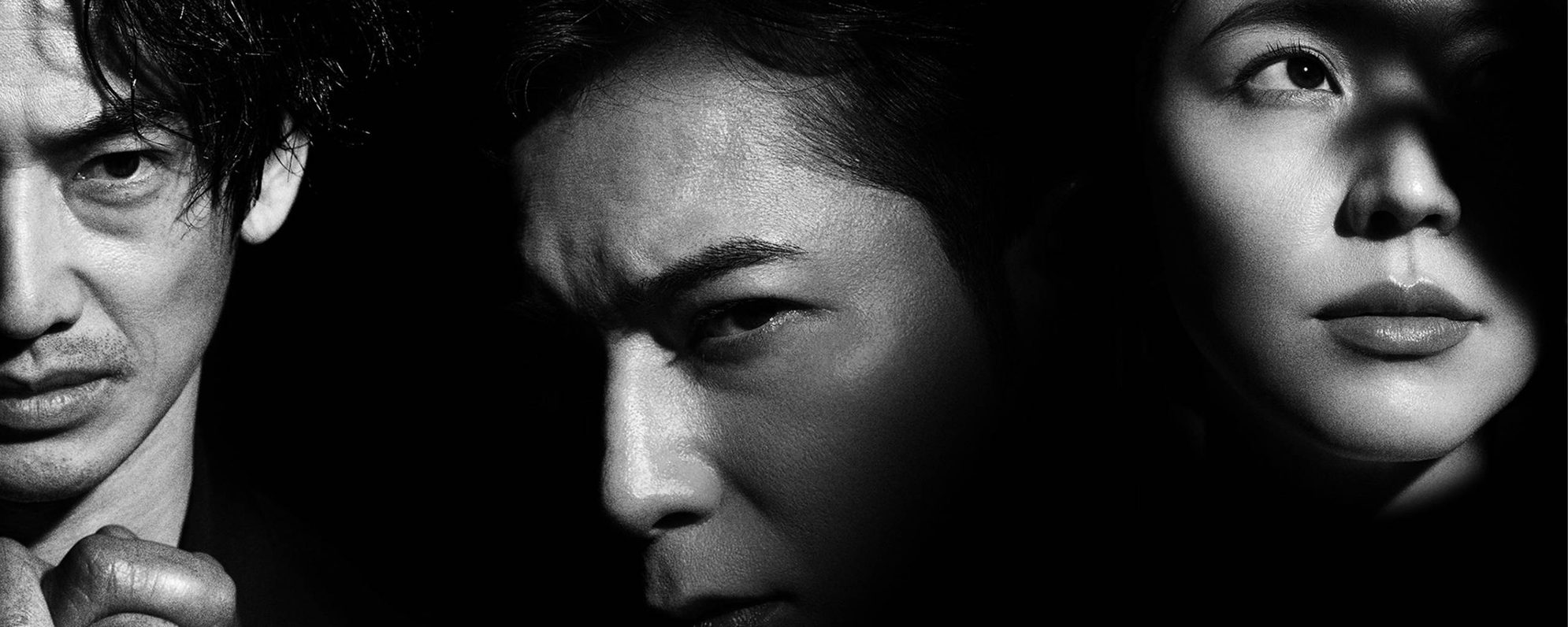

The Japanese singer, actor and heartthrob Matsumoto Jun, who I’ve always thought of as an Oriental David Cassidy (thus showing my age), will make his UK acting debut later this year when he appears in acclaimed playwright Hideki Noda’s very loose adaptation of the Brothers Karamazof at Sadler’s Wells. Jun is, not to sell him short, a superstar in Japan. It should be quite an event.

In many ways, Japan (and South Korea’s) talent factory is like a throwback to the Hollywood star system of the 1920s to 1960s

If you can’t get your head round the David Cassidy analogy, perhaps Harry Styles would be more meaningful, though even the former One Direction star would struggle to attract the kind of devotion inspired by Jun (it really is more like Cassidy – look him up). In fact, it is entirely possible that the tickets for the London shows will sell out in hours or even minutes, with many snapped up by his legions of scarily fervent fans in Japan (Jun has 1.2 million Instagram followers) who would be quite willing to break the bank to visit England for a couple of days just to see him live.

It is rare to see this sort of celebrity adoration in the West these days. Jun and his band Arashi (he is probably equally well known as a singer and an actor) recall the days of Beatlemania, days that have never really gone away in Japan. Tickets for the Tokyo run of Noda’s play have been rumoured to have changed hands for up to £5,000; and with respect to Hideki Noda, a serious playwright, that is purely down to Jun’s presence. Stars like Jun are called ‘idols’, and for a reason.

What makes ‘MatsuJun’ (he’s so big he is known by this one-word nickname) so special? He is a decent enough actor and a pretty good singer, but the truth of his success is probably down mainly to aesthetics and especially facial geometry. There can be few more beauty-obsessed entertainment cultures than that of Japan, and Jun, with his handsome but sensitive features and fulsome head of immaculately coiffured, heavily invested-in hair, has a multi-generational appeal.

He is a fantasy boyfriend/husband/best friend for the youngsters. There is not a hint of danger about him. In his TV appearances and umpteen adverts, he generally plays wholesome types, an immaculately groomed if casually attired modern man who will don a pinny and take his turn with the housework. One even has him just dandling a baby. For older women, he’s either evocative of the love they never quite realised or the perfect son-in-law. He screams eligibility.

Is there something a little unhealthy about this? The Jonny Kitagawa scandal – involving decades of sexual abuse allegations against the late founder of Tokyo’s most powerful talent agency – is still fresh in the minds of Japan watchers, even if little discussed in the country itself. Jun seems in control of his career now, but he did start very young, with a personal interview with the notorious Kitagawa, of BBC documentary infamy, himself. And while Jun has been canny enough to diversify and survive, and not get fat or go bald, for every entertainer who survives, there are many shooting stars who fade quickly. Some are mocked as no more than good-looking clowns, obaka aidoru – dumb idols.

It’s a rough old world with an ugly underside. In many ways, Japan (and South Korea’s) talent factory is like a throwback to the Hollywood star system of the 1920s to 1960s, where the talent was almost literally owned by the studios, who crafted personas and backstories on to their charges, occasionally even arranging marriages where appropriate (Rock Hudson, Judy Garland). There is no suggestion that Matsumoto Jun’s career has been micromanaged to quite that extent – though next to nothing is known about him. He is probably not a cipher, but many in the business clearly are. It was almost admitted once when the singer and idol Ayumi Hamasaki, known as much for her outrageous make-up as her musicianship, declared that she opposed her recording company’s decision to market her as a ‘product’ and not as a ‘person’.

There is another issue: some disquiet in the theatrical community about the quasi-religious devotion to ‘talents’ (as the Japanese call them) parachuted into serious theatrical productions. Hideki Noda has loyal fans, many of whom will struggle to get tickets for the new show thanks to the mania surrounding Jun. Imagine if Taylor Swift were suddenly cast in Hedda Gabler at the Old Vic and how the regular audience might be pushed to one side.

Live theatre in Japan is marketed through big star name recognition, and you achieve that recognition not by graduating from the Japanese Rada or treading the boards, but by either fighting for a space in the inane cavalcade of variety shows and soppy dramas or forcing yourself to the front in one of the boy or girl bands – which can be enormous (two of the most famous have 48 members). And always, looks are paramount. The aesthetically challenged, however gifted, need not apply. It’s not exactly in the finest traditions of the West End. With no offence to Jun, John Gielgud might be turning in his grave at these priorities. But it should be an interesting spectacle for British theatre-goers, and I am greatly looking forward to Lloyd Evans’ review.

Comments