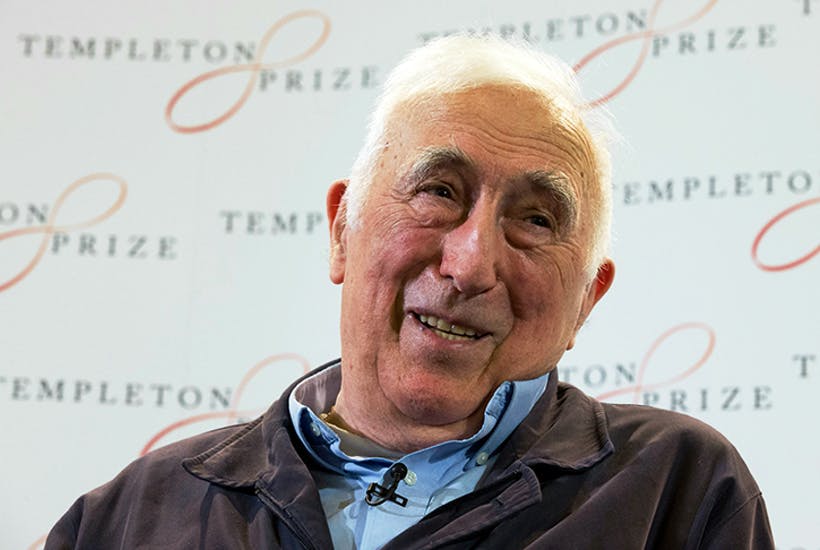

The fall from grace of Jean Vanier is truly a sad story. The founder of the L’Arche communities did extraordinary work, practical, intellectual and spiritual, to advance the idea that those suffering mental handicap had much to teach the rest of us. His was a radical idea about what community can be. Now, however, L’Arche has accepted a report that Vanier, who died last year, had sexual contact with six women from the 1970s onwards. There is no suggestion of any exploitation of the handicapped. Unlike so many claims in abuse cases, these ones seem to have been carefully investigated. The women (all adults) were his devoted followers. Vanier appears to have told them that by getting close to him they would also get closer to God. In this, he was probably following his friend, a Catholic priest, Fr Thomas Philippe, who advanced such ideas and practices, and was duly disgraced. Archive evidence shows that Thomas Philippe and Vanier kept in touch, the latter helping protect the former. About five years ago, I was sounded out to write a biography of Vanier. I had heard him speak a couple of times and had been deeply impressed. I did have a tiny worm of doubt about the man — not about anything he said, but occasioned by his strong charisma. His ascetic, craggy good looks and incantatory voice reminded me of the somewhat bogus Laurens van der Post, and I noticed that he attracted ardent women. Remembering the history of sexual abuse by those with spiritual power, I pointed out, though I knew nothing against him, how dismal it would be to embark on the tale of a good man and then discover bad facts . This was a small factor — lack of time being the bigger one — in my refusal of the task.

The abuser’s capacity to persuade others, and perhaps even himself, that sexual contact (in Vanier’s case, it appears not to have been full intercourse) is what God wants is, obviously, evil. It is also heresy. It derives from the idea that some people are specially chosen by God and therefore exempt from His rules. The medieval Albigensian heresy held that some people were ‘parfaits’ — which gave them a licence for what the 1960s would call ‘free love’. As Fr Thomas Philippe is supposed to have put it to one of his victims, ‘When one arrives at perfect love, everything is lawful.’ Can anything of Vanier’s reputation survive this catastrophe? I do hope so. The fact that nobody’s ‘parfait’ does not mean that no one does good. L’Arche survives, and deserves to, and it would not exist without Vanier. ‘Every saint has a past, every sinner has a future.’

Andrew Adonis is an impressive man, one of the few in the Labour party who never compromised with the left. Yet he is also an illustration of this column’s claim that the Labour pro-European ‘moderates’ are just as adrift from reality as are the Corbynites. In an article in New European last month, headlined ‘A Star in the West’, Lord Adonis praised the Irish prime minister, Leo Varadkar, ‘as he steers Ireland towards a unity and confidence it has never previously known’. In the Adonis theory, the Varadkar/Boris Johnson deal over Brexit would crown the ‘lasting rapprochement’ accomplished by John Major and Tony Blair in the 1990s and create a united Ireland: ‘After all, only 11 months separated the fall of the Berlin Wall and German reunification.’ Since then, Mr Varadkar has lost the Republic’s general election, in which Lord Adonis predicted he would ‘consolidate his position’, and has resigned. The party with the most votes is Sinn Fein. There is much to be said for the ‘modernised’ and ‘secularised’ politics which Lord Adonis hymns — at least when contrasted with bigoted and antiquated politics — but he should recognise that millions of EU citizens feel cheated by such politics. The European Union has become the papacy of secularisation and modernisation, infallible in its own mind, harsh to its unruly flock.

Tessa Keswick has just brought out a book about her travels in China and her development of Chinese friendships over 40 years (The Colour of the Sky after Rain). Tessa has been my friend for most of that time, as has her husband Henry, who bought this paper in the 1970s, appointed Alexander Chancellor as its editor, and thus set it on the path to success. So at first I thought that I shouldn’t comment on the book. I changed my mind, however, when I noticed a reluctance to review it — perhaps because Henry is very rich (he recently stepped down from running Jardine Matheson, the Far East conglomerate, after nearly half a century), and because Tessa, who made some of her trips through contacts made as his wife, is therefore seen as not properly qualified. In reality, these are not objections, but advantages. Henry’s money and connections got Tessa to interesting places with interesting people. Her own commitment, and the fact that she was a woman with leisure in what was almost wholly a man’s world of business, gave her the gift of time — living with a Chinese family to learn Mandarin, for example — which most visitors lack. Tessa’s travels begin with a country so poor that lorry drivers rarely switch on their lights in the dark, thinking it saved petrol, and end with the stupefyingly rich superpower of today. The book is honest. Tessa loves China, and is persuasive about the virtues of its people — their directness and their honesty once trust is achieved. But she does not shy away from the grimness of a political order which remains adamantly opposed to basic human freedom. One of the most powerful passages comes when she and Henry meet Bo Xilai, the rising star of Chinese politics, on the day before his public disgrace — his ‘utterly mournful’ eyes, and the ‘exceptionally tall men in dark suits’ who suddenly surround him. The book is also Tessa’s gesture of love for Henry. She wrote it, without telling him, when both of them were very ill. Henry was born in Shanghai, where his father traded, but driven out by the Japanese and later kept out by the communists. This book celebrates, obliquely, how he has won so much back.

Comments